Back to StoriesPainting The Wild Sources Of Moving Water

June 16, 2021

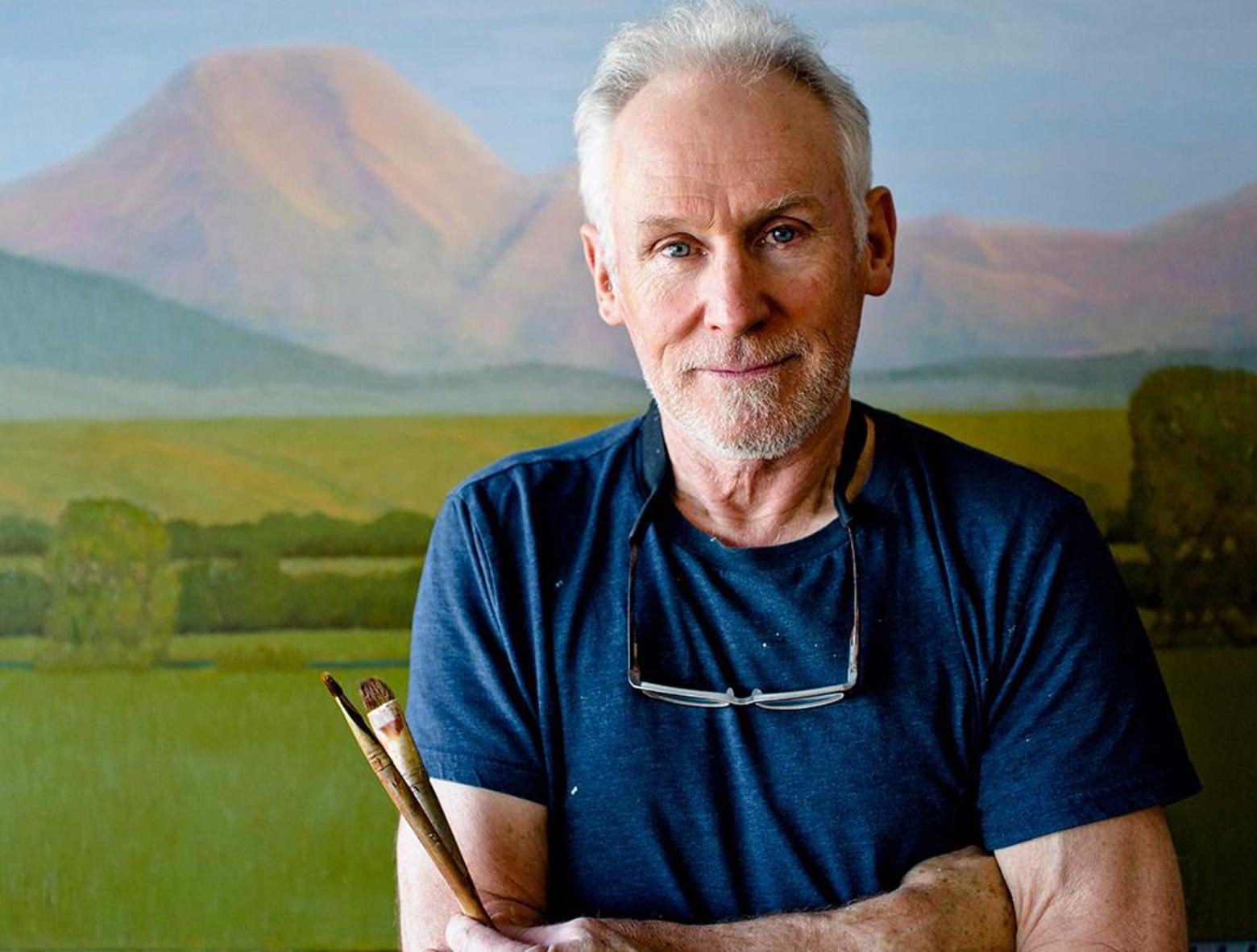

Painting The Wild Sources Of Moving WaterDave Hall celebrates the lifeblood of Greater Yellowstone that reaches millions downstream

by Todd Wilkinson

For many rivers, discovering what remains of their wild essence requires heading upstream. Humans throughout time have exacted tolls from our waterways and in terms of their character lower reaches often disappoint for the trappings of civilization that have wrung the life out of them.

In Mexico at the Sea of Cortez where the Colorado trickles into the delta with the pulse of the Green a faint hindsight confluence; in the Northwest where the Columbia churns into the Pacific having absorbed the Snake; and south of New Orleans where the Mississippi finds the Gulf long forgetting the flows of the Missouri, there’s little hint that, were you to trace each course back to the common region where they began—Greater Yellowstone along the Continental Divide—you may find the tracks of grizzly bears imprinted in the melting snowpack.

Dave Hall will tell you there are lots of extraordinary places on planet Earth to dip a paddle, cast a line and set up a portable easel, but few water corridors remain in the developed world where a human can bump into the full complement of original four-legged megafauna that were there half a millennium ago.

Only one region still boasts that in the Lower 48 and it is a wellspring for tens of millions of Americans. Nurturing are Greater Yellowstone's near-mythical rivers. They, distant, help deliver some of the last remaining salmon smolts back to the sea, and give ancient paddlefish the higher flows they need to spawn, and they carry rafters through the Grand Canyon.

At Last Chance, Idaho, within eyeshot of the Henrys Fork of the Snake River, Hall takes his work commemorating rivers seriously.

Greater Yellowstone has been famously painted by a glorious parade of visual artists dating back to the Hudson River School. From Thomas Moran—whose sketches and finished oil paintings convinced Congress to create a new kind of nature preserve called Yellowstone National Park—to Albert Bierstadt who portrayed the geyser basins, Tetons and Wind River Range, the fine art legacy continues de rigueur in the 21st century.

Until June 19, 2021 a collection of 40 new Hall oil paintings, fresh off the easel, are being featured in a one-man exhibition at Harriman State Park in eastern Idaho. Even if you can't physically make it, you can see the works by clicking here or by visiting Altamira Fine Art in Jackson Hole and Tierney Fine Art in Bozeman. Apart from these gems there's also Hall's acclaimed "Yellowstone Suite" series and as part of his commitment to journalism and protecting the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, he is donating proceeds from sales of Yellowstone Suite paintings to Mountain Journal in the hopes it will help us fund another reporting position.

Hall’s work is known for melding color fields reminiscent of Mark Rothko and harmonious tonal bands in a way that is both contemporary and timeless without being sentimental. It shares a kindredness with the moody representations of the Northern Rockies synonymous with the late Russell Chatham, who spent most of his adult life along the Yellowstone River in Paradise Valley near Livingston, Montana.

Both are known for their masterful ways of reading the water and haunting it during crepuscular hours.

“I am moved by the half-light of dawn and dusk, and my paintings are inspired by the Greater Yellowstone country of Idaho, Montana and Wyoming,” Hall says. “A piece of my heart resides there, due in large part to the poetry associated with the convergence of family and friends, moving water and mayfly hatches.”

Novelist Thomas McGuane, a diehard angler and longtime friend of Chatham, says of Hall: "Dave Hall is a painter with his feet and mind in the natural world, a place he knows with uncommon intimacy."

Hall doesn’t “paint fish” but his soothing scenes of the storied streams where trout dwell make anglers and river people swoon. There have been countless edges of day when even if the bite is on Hall will set the rod aside and just stand in the evanescence, absorbing it as a kind of experiential osmosis.

I had known of Hall’s work and met him a few years ago when he was a painter in residence at the Taft-Nicholson Center, operated by the University of Utah in the Centennial Valley of southwest Montana.

A New Englander by upbringing, Hall graduated from the University of New Hampshire and Yale University’s School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Today he divides his seasons between Salt Lake City and Last Chance.

Besides operating an on-line art gallery he shows his work in Greater Yellowstone at ABanks in Bozeman and Altamira Fine Art in Jackson, Wyoming.

Every year, he delivers about 25 paintings and has several going at any one time. I asked him about his heroes.

"I like people who show courage. From an art perspective, I’ve admired the abstract expressionists — Rothko et al — for their work and their journey into the new and experimental,” he said.

“Most artists, I think, have had the experience of being seduced into painting what has worked in the past, that is, what is recognized as good (if not inspired) and what will sell in a gallery. David Bayles' wonderful book Art and Fear speaks to this.”

In 2018, Hall's well-received book Moving Water: An Artist’s Reflections on Fly Fishing,

Friendship and Family was published. Now he is working on a series of large abstract landscapes called The Harriman Suite — looking at the Greater Yellowstone, and the Henry’s Fork country in particular,

Widely collected, one of Hall’s most ambitious paintings is Dawn on the Henry’s Fork from 2009. “I see it as the essence of how I feel about my decades on that river. It was completed very quickly without a great deal of planning — more emotion than thought," he notes.

The original is owned by collectors in Salt Lake, and about five prints were made. "One is in our home, one hangs at Trouthunter on the River in Last Chance and another hangs in Executive Director Brandon Hoffner’s office at the Henry’s Fork Foundation’s campus in Ashton, Idaho," he says.

A devoted conservationist, he believes in giving back and has donated over $40,000 to land and wildlife protection causes based on the sale of his paintings. He believes that the tens of millions of Americans who have an unknowing connection to Greater Yellowstone because of the water flowing at their taps far downstream, wetting their gardens, providing recreation and habitat to wildlife ought to reflect on the source and become conservation advocates for protection of the headwaters.

Mountain Journal caught up with Hall and parts of our interview are below.

TODD WILKINSON FOR MOUNTAIN JOURNAL: Russell Chatham spoke about, and his work reflected, a new kind of contemporary, representational impressionism in the inner West that conveyed to viewers feelings of places. Do you identify with his take?

DAVE HALL: Very much so. My work has been called moody and ethereal, descriptions that I’ve always taken as honoring, as it’s how I often see and feel about landscapes and my time experiencing them. I’m drawn to images in low light — dawn, dusk, fog, a calm snowfall, situations and locations where it’s difficult to make out detail. I don’t know why this is; it just is.

MOJO: How did your way of relating and inter-relating with landscapes begin and evolve?

HALL: I was introduced to fly fishing at a young age. Two grandfathers were passionate about the outdoors. By seven or eight I was tying flies and heading out at dawn in rural New England chasing brook trout. It was a vital part of my upbringing — roaming about in New England woodlands. I suppose I took it for granted then but without doubt it has had a huge influence on how I feel about landscapes today.

MOJO: How did art emerge as a way of thinking about the outdoors?

HALL: There was family art throughout the house. My Dad was a civil engineer and a wonderful photorealistic painter. He could paint anything. His mother — my grandmother — was a working artist for 60 years, getting her start with fashion illustration for Boston newspapers. She worked in all mediums and taught for many years.

A great, great grandfather Thomas H. Snow was a New England sporting artist in the second half of the 19th century. I have many of his oil paintings of brook trout, grouse, woodcock, waterfowl, as well as his bird dogs, along with his sporting journal from 1853 to 1871. Beautiful stuff. He greatly influenced his grandson — my grandfather — who gave me my first fly rod.

MOJO: The era when Snow painted merged with the start of the Golden Age of Illustration and the Hudson River School in the Northeast. Many artists were influential in giving Americans a vicarious look at the West. How did having exposure to works that grew out of those movements affect you?

HALL: While I have no formal art training, fine art was always around me and I knew for a long time that art — and landscapes in particular — is where I’d end up. And I always knew what I’d paint, certainly influenced by those early years in the New England woods and the paintings throughout our home.

MOJO: So many great artists have portrayed and are portraying Greater Yellowstone. What part of the region most speaks to you?

HALL: The Henry’s Fork country and the Harriman Ranch (site of Harriman State Park) in particular is where my heart is. Harriman is a national treasure. As a fly fisherman I see it as one the world’s great trout fisheries but it goes too to the astounding beauty of this spot in the Greater Yellowstone — the early morning mist over the river and the presence of grizzly bears, wolves, river otters and great gray owls. And to the knowledge that it’s been protected.

MOJO: Few contemporary artists have featured the western tiers of Greater Yellowstone more than you have. Lots of Utahns have places there. What speaks to you about it?

HALL: It is wild and represents an important corridor for wildlife moving between Greater Yellowstone and other ecosystems to the west and north. In MovingWater, I wrote, “The thing about fishing in grizzly country is this: you’ve got your bear spray close but there’s still a chance (small) you’ll get eaten.”

MOJO: You are a believer in the protection of land as wilderness and you insinuate your admiration for the character of Greater Yellowstone in your work.

HALL: Wilderness…add a bull moose, river otters, wolf tracks in the gravel meanders, ospreys, eagles, ocher grasses to your chest, and silence but for the wind across the meadow and you realize that this place has changed little since Thomas Henry Snow was hunting ducks on Boston’s Back Bay marshes before the Civil War.

MOJO: Your love of angling has fueled many adventures. What separates Greater Yellowstone?

HALL: Twenty years ago I fished with friends on New Zealand’s South Island. The landscapes are beautiful and spectacular. But with no wolves and bears — no large carnivores in fact — and the deer introduced, it struck me immediately that New Zealand had a very much different feel than that of the Greater Yellowstone. It was a real and profound feeling.

Contrast that with a canoe trip that Becky and I took with two Bozeman friends in 1980. We paddled to the bottom of the Southeast Arm in Yellowstone and camped and explored for a week the Upper Yellowstone River country. Not much compares to waking in your tent at 2 a.m. convinced that what you hear outside is a griz. For me that’s the essence of wild country.

MOJO: The response to your work has been tremendous. What are your collectors seeking?

HALL: I suppose they’re seeking the same thing we all look for in the outdoors — quiet, solitude, a feeling of calm and peace of mind.

MOJO: As a painter, what concerns you about the future of Greater Yellowstone?

HALL: The number of people and the growing numbers among us who can’t or don’t relate to the experience and value of wilderness, along with the endless number of associated issues. Mountain Journal gives me a glimmer of hope.

MOJO: What do you absolutely positively want us to relate in this piece?

HALL: That we all can/should do what we can—however small—for the Greater Yellowstone.