January 7, 2018

What Do The Long-term Trends For Grizzlies In Lower 48 Really Look Like?Lance Olsen Says Climate Change And Human Development Trends Create A Lot Of Uncertainty

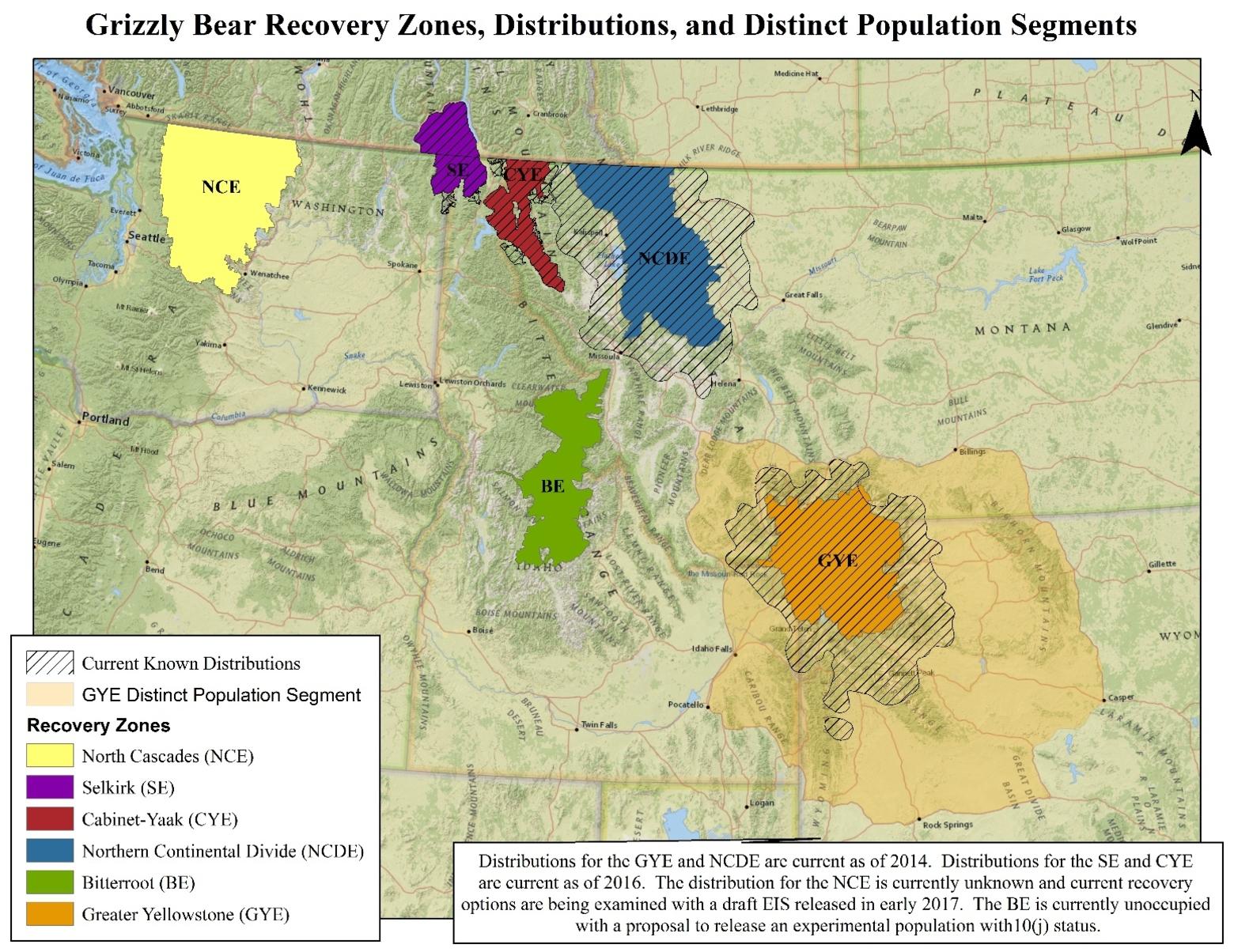

We’ve recently seen reports that the grizzly populations in the Greater Yellowstone and Northern Continental Divide Ecosystems are growing, expanding their range, and getting into trouble when their expansion takes them up against the human population. True enough, but it’s only part of the story.

The issues facing bears in both places echo off each other, and there have been comments suggesting that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which just recently de-listed grizzlies from federal protection in Greater Yellowstone, may soon do the same in the Northern Continental Divide.

A recent federal Biological Assessment on grizzlies’ current situation in the Northern Continental Divide region (which covers wildlands stretching from the outskirts of Montana's state capital city, Helena, northward to the U.S.-Canada border) says the human population in Montana has also grown, and “at a relatively high rate during the past few decades, and growth is expected to continue.”

What we see here is a collision course for two expanding populations, with consequences for the future of bears – and much else.

Grizzlies will likely see something similar this time around. The Biological Assessment says “Increasing residential development and demand for recreational opportunities can result in habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, and increases in grizzly bear-human conflicts.”

The Assessment does admit that, “These impacts are likely to intensify.” But ample doubt surfaces when the Assessment claims that, “appropriate residential planning... can help mitigate these impacts.”

Alas, “appropriate residential planning” is left vague, undefined, amounting to little more than wishful thinking, even though the Assessment admits that development “has the potential to have cumulative adverse effects on the Northern Continental Divide grizzly bear population.”

The Assessment claims that, “Monitoring of population status will provide a mechanism to identify areas of concern so that appropriate preventive or corrective actions can be taken.” Again, the appropriate actions are left undefined, leaving a big hole in hope for lasting grizzly recovery. And it’s far from clear how monitoring the situation leads to these undefined actions.

On the climate front, the Assessment claims that impact on habitat made of plant species or plant communities “is not possible to foresee with any level of confidence.”

But the closely-related Draft Grizzly Bear Conservation Strategy says, “Most grizzly bear biologists in the U.S. and Canada do not expect habitat changes predicted under climate change scenarios to directly threaten grizzly bears.”

These expectations omit important evidence on climate and habitat.

For just one example of evidence on climate effects on habitat, scientists have found that “suitable days for plant growth disappear under projected climate change.”

That said, even if risks for habitat wouldn’t threaten grizzlies directly, a 2008 article in Science reported that "Direct effects of climatic warming can be understood through fatal decrements in an organism's performance in growth, reproduction, foraging, immune competence, behaviors and competitiveness."

A 2013 article in the Journal of Animal Ecology confirmed that analysies, reporting that, “ ... organisms have a physiological response to temperature, and these responses have important consequences .... biological rates and times (e.g. metabolic rate, growth, reproduction, mortality and activity) vary with temperature.”

These important risks go unmentioned in the Assessment and Draft Conservation Strategy.

So, how bad can heat’s impact get? The authors of a report in the distinguished science journal Nature conclude that, “Our results suggest that it doesn't make sense to dismiss the most-severe global warming projections.”

The Assessment mentions drought as a factor in fire, but omits mention of evidence that drought can force wildlife into (expanding) human-dominated areas. All in all, risks from heat and drought are largely and wrongly omitted from both the Assessment or the Draft Conservation Strategy.

Given these documents’ vagueness and omissions, it’s not easy to feel secure about proposals to delist the grizzlies of the Lower 48 states.