Back to StoriesThe Yellowstone Caldera Is Aflutter With Recent Shakes, Rattles and Rolls

February 21, 2018

The Yellowstone Caldera Is Aflutter With Recent Shakes, Rattles and RollsThe ground beneath Yellowstone continues to be aswarm with earthquakes. Find out why

Over the past several days, an earthquake swarm has been ongoing at Yellowstone.

Before you read any more, keep in mind that swarms like this account for more than 50 percent of the seismic activity at Yellowstone, and no volcanic activity has occurred from any past such events.

As of the night of February 18, over 200 earthquakes have been located in an area eight miles northeast of West Yellowstone, Montana. Many more earthquakes have occurred, but are too small to be located.

Does the location for this swarm sound familiar? It should..

This is approximately the same place as last summer's Maple Creek swarm, which included about 2400 earthquakes during June-September 2017.

This is approximately the same place as last summer's Maple Creek swarm, which included about 2400 earthquakes during June-September 2017.

In fact, the current swarm may be just a continuation of the Maple Creek swarm, given the ongoing but sporadic seismicity in the area over the past several months.

The present swarm started on Feb. 8, with a few events occurring per day.

On Feb.15, seismicity rates and magnitudes increased markedly. As of the night of Feb. 18, the largest earthquake in the swarm is M2.9, and none of the events have been felt. All are occurring about five miles beneath the surface.

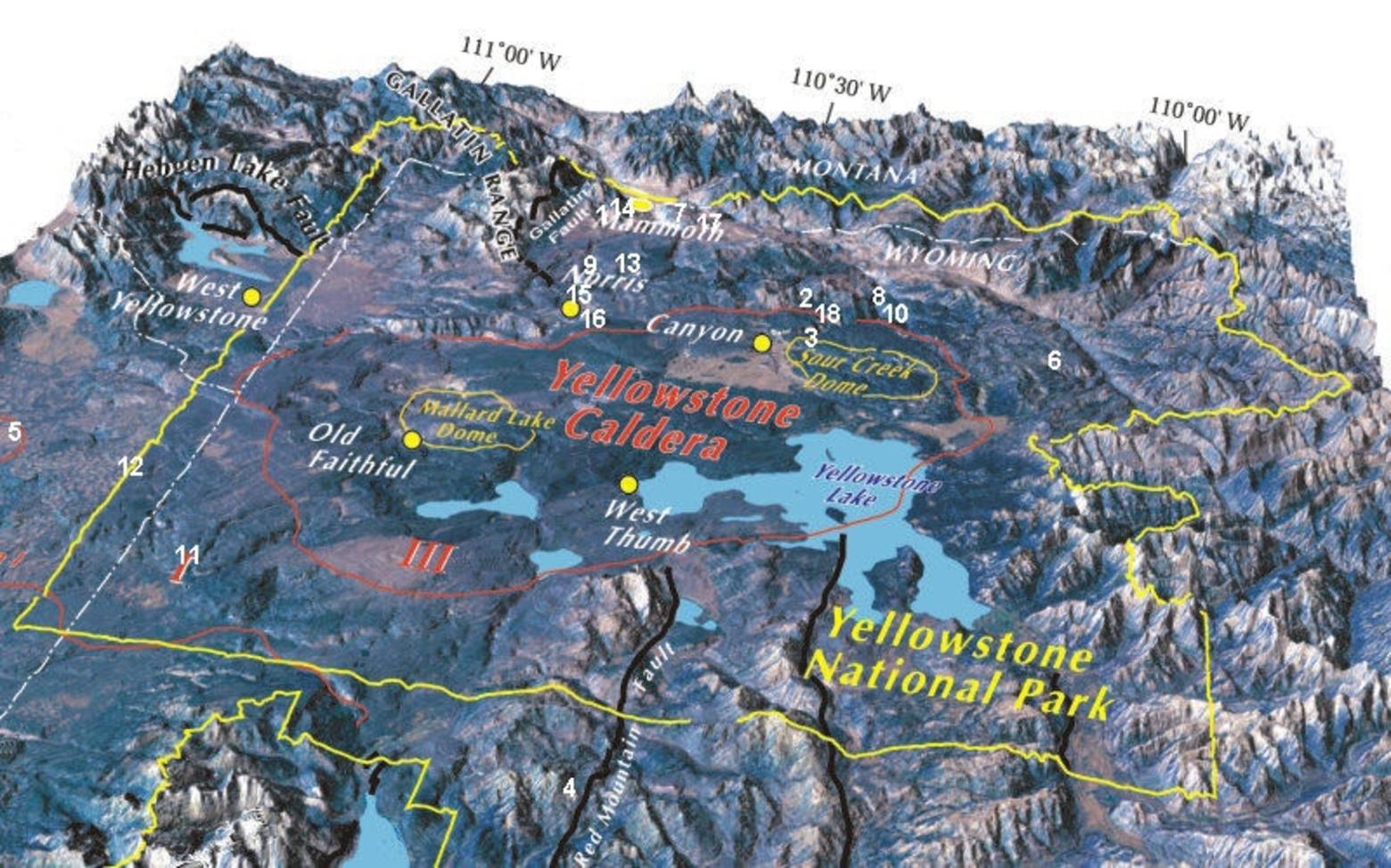

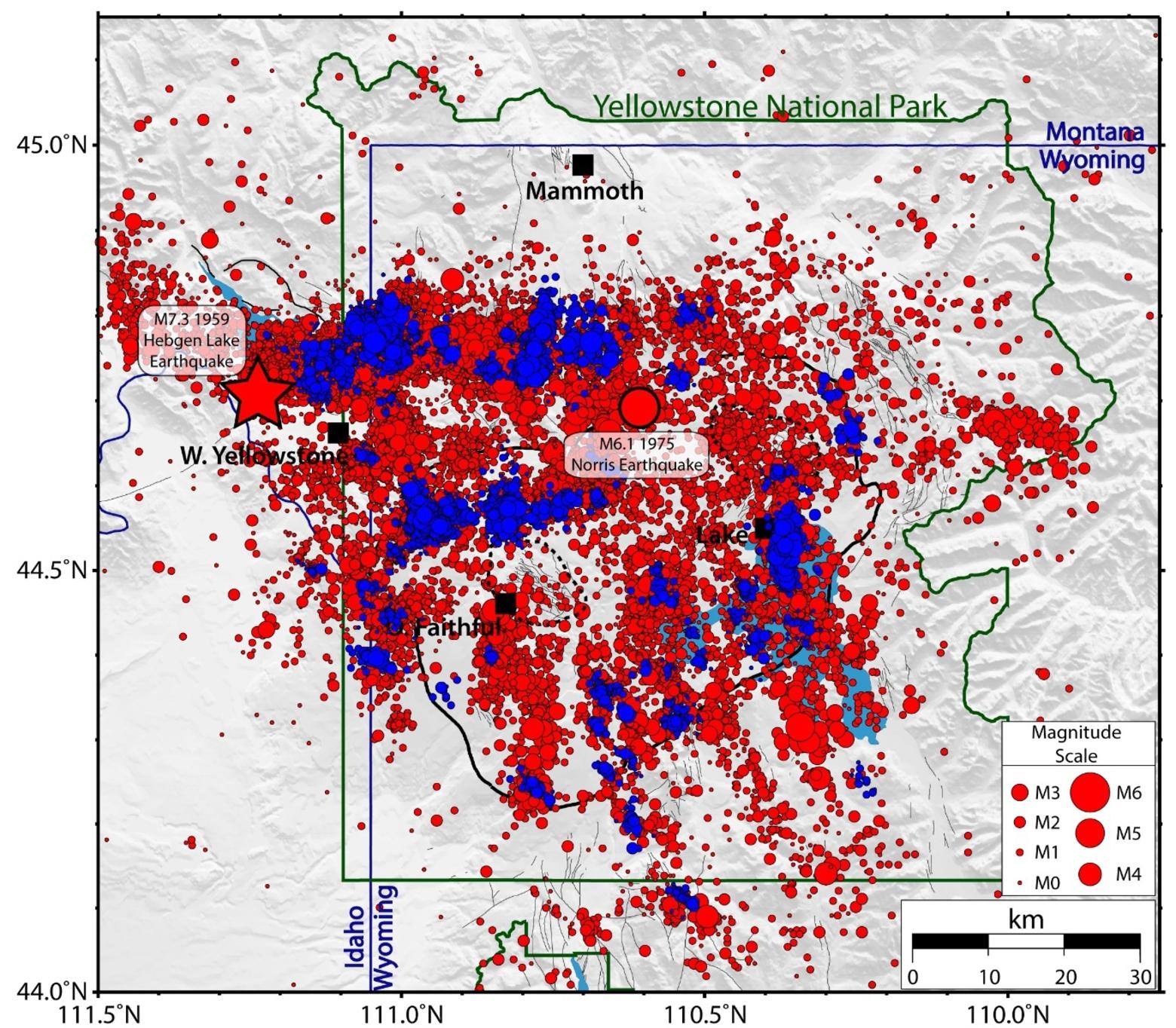

What is causing this swarm seismicity? And why do swarms always seem to be happening in this part of Yellowstone National Park? A view of historical earthquakes in the region shows that the area is a hotbed of seismicity.

The University of Utah Seismograph Stations, which are responsible for seismic monitoring in the Yellowstone region, use a standard definition of an earthquake swarm—an increase in earthquake rates within a given area over a relatively concentrated period of time without a single large "mainshock."

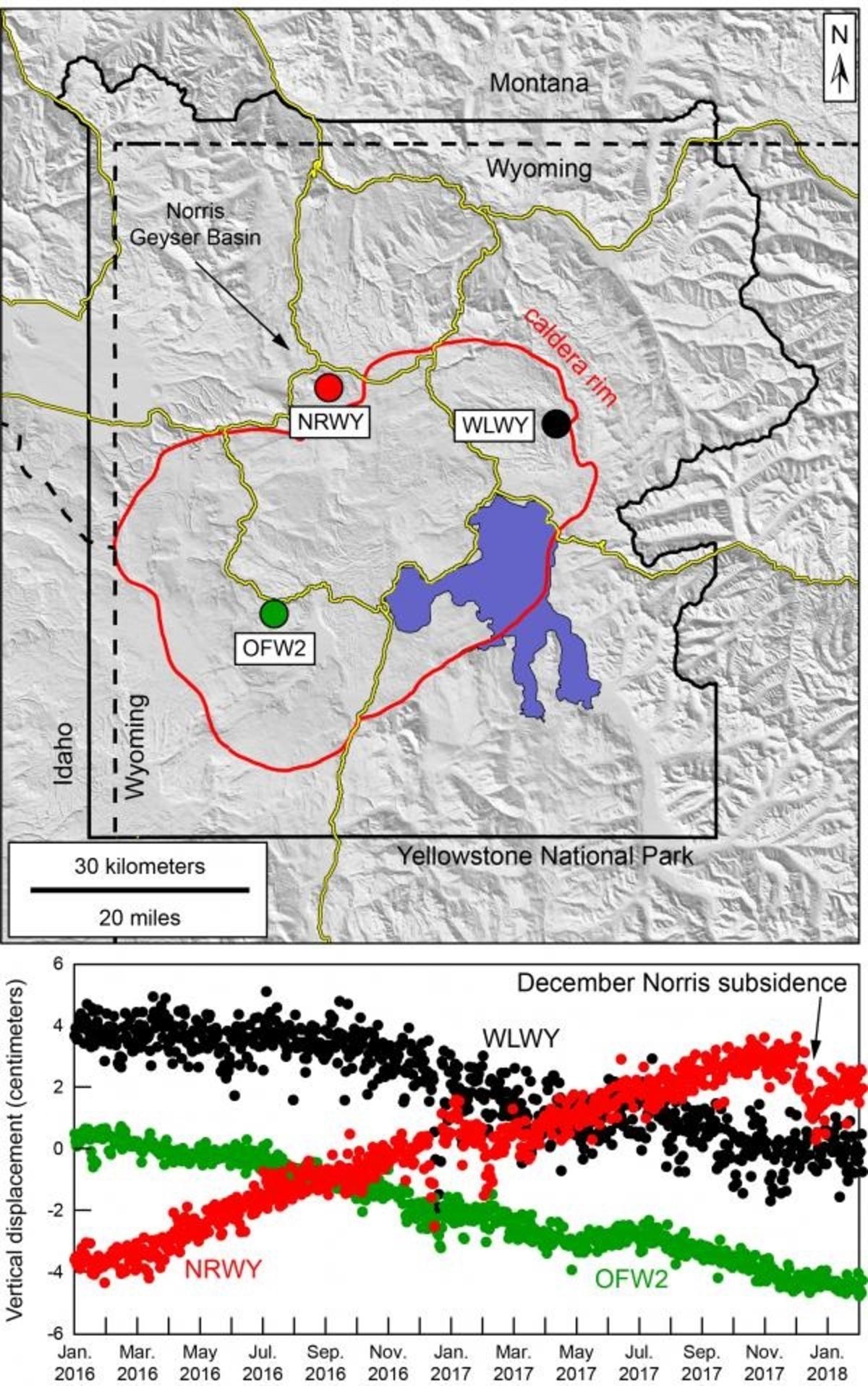

Swarms reflect changes in stress along small faults beneath the surface, and generally are caused by two processes: large-scale tectonic forces, and pressure changes beneath the surface due to accumulation and/or withdrawal of fluids (magma, water, and/or gas).

The area of the current swarm is subject to both processes. The largest historic earthquake in the region, the 1959 M7.3 Hebgen Lake event, was due to faulting that has its ultimate cause in the fact that the western United States is being pulled and stretched apart—this is what results in the "basin and range" topography of much of the region.

But we also know that there is a tremendous amount of fluid in the subsurface, including hydrothermal water and gases that come to the surface at nearby Norris Geyser Basin—the hottest thermal area in Yellowstone National Park.

The current and past earthquake swarms reflect the geology of the region, which contains numerous faults, as well as fluids that are constantly in motion beneath the surface. This combination of existing faults and fluid migration, plus the fact that the region is probably still "feeling" the stress effects of the 1959 earthquake, contribute to making this area a hotbed of seismicity and swarm activity.

While it may seem worrisome, the current seismicity is relatively weak and actually represents an opportunity to learn more about Yellowstone. It is during periods of change when scientists can develop, test, and refine their models of how the Yellowstone volcanic system works. Past seismic swarms like those of 2004, 2009, and 2010, have led to new insights into the behavior of the caldera system. We hope to expand this knowledge through future analyses of the 2017 and 2018 seismicity.

The earthquakes, too, serve as a reminder of an underappreciated hazard at Yellowstone—that of strong earthquakes, which are the most likely event to cause damage in the region on the timescales of human lives. As recently as 1975 there was a M6.5 event in the area of Norris Geyser Basin.

In future columns, we will be sure to share the results of research into Yellowstone's seismic swarms. We will also keep you informed about current earthquake activity, both in this column and through our monthly updates. Stay tuned!

EDITOR'S NOTE: The essay above was written as part of the Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles penned weekly by scientists and collaborators affiliated with the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. Mike Poland is a USGS research geophysicist and YVO Scientist-in-Charge, and Jamie Farrell is assistant research professor with the University of Utah Seismograph Stations and YVO Chief Seismologist.