Back to StoriesClose Encounters Of The Avian Kind

November 21, 2019

Close Encounters Of The Avian KindAs Phil Knight writes, human-animal curiosity and contact extends both ways

Editor's Note: This story has been updated. Three paragraphs at the end of Phil Knight's piece were inadvertently left out. MoJo regrets the layout error. They are there now. Enjoy.

By Phil Knight

Wherever I travel I seek to see and experience the wildlife that live there.

I’ve been fortunate to see Greater Yellowstone grizzly bears flipping rocks in search of Army cutworm moths, whales breaching off Antarctica, giant cockatoos foraging in the Tasmanian rainforest, New World monkeys racing through the tree tops in Costa Rica, barren ground caribou running across the tundra, a mountain lion silhouetted on a snowy ridgetop, eagles flying at eye level in the Tetons, and great schools of rainbow-hued fish swirling around coral reefs.

But sometimes a wildlife encounter goes beyond mere observation.

Who has not had an intense meeting with a wild animal, looked into its eyes, noticed the intelligence, the wonder, the desire to make sense of what it is seeing? Who has not wished to converse with such a creature, to hear their take on the world and on humanity (though we may not like what they have to say)?

Once in a great while the line between the observer—me—and the animal bends, roles are reversed, and I find myself being scrutinized by curious eyes. And even rarer still, a wild animal willingly makes contact with me – direct physical contact. No, I don’t mean I get attacked, though I have had some close calls with angry moose. Nor do I mean bitten by a deer fly.

What I am getting at is benign contact, when a small, harmless animal lands or walks on me. And I am transfixed by the experience.

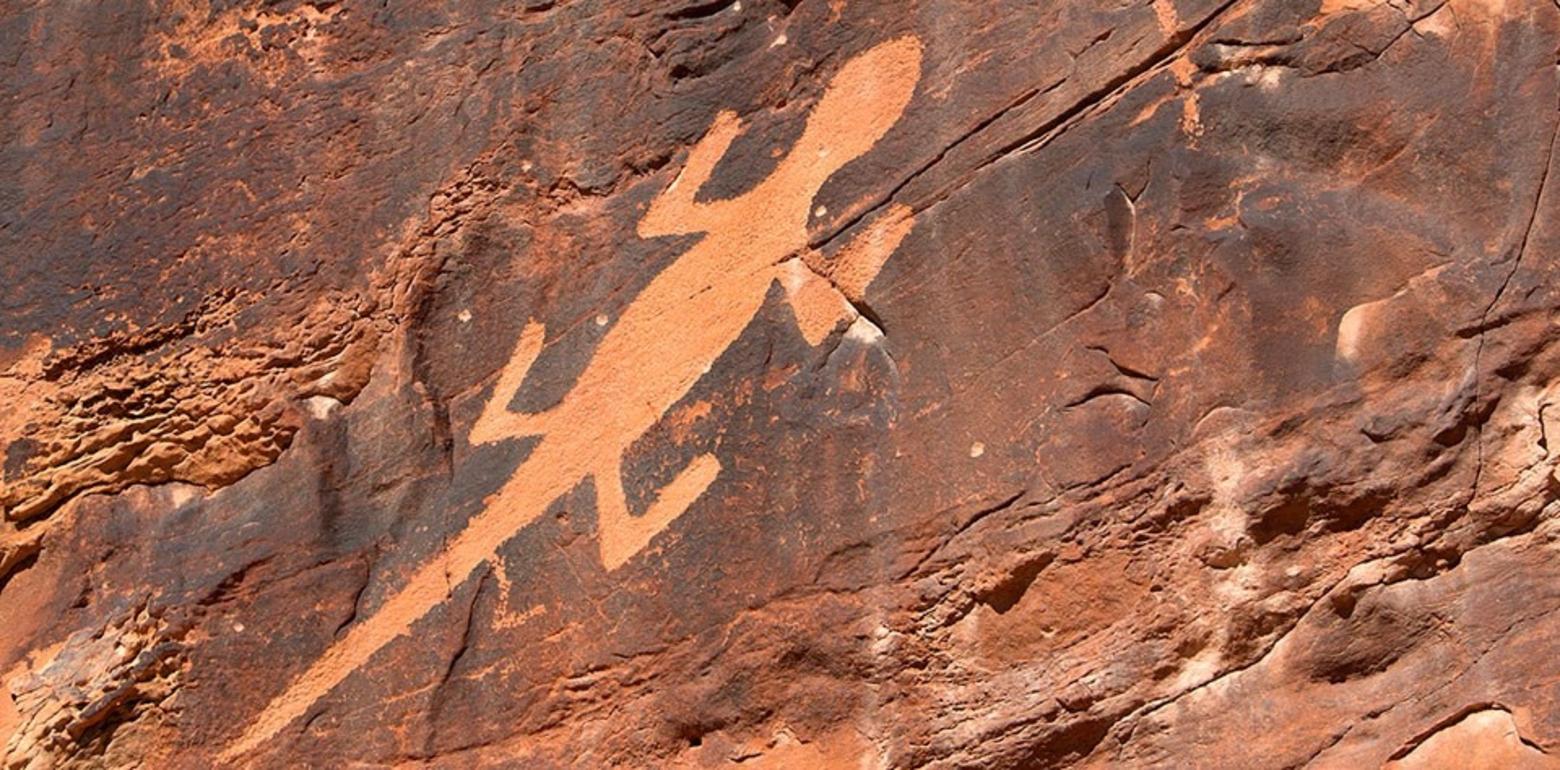

It happened this fall. Canoeing with my wife and a friend down the Green River in Utah through the vast vertical landscape of Canyonlands National Park, we camped for two nights at a spectacular spot called Bonita Bend.

Great blue herons fished the shallows and geese flew overhead honking. Deer waded and huffed in the shallows in the dark. Lizards are everywhere in this red rock country, and you get accustomed to their scurrying in the dry leaves. I love seeing them.

One lizard stepped outside of his usual boundaries.

I was relaxing in my camp chair, reading Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire, my wife reading nearby, when we noticed a decent sized lizard coming in my direction. We stayed still to see what he would do. First he jumped on my pack—a bold move but not too unusual. His next move really surprised me. Looking straight at me, he suddenly leaped onto my shoulder!

Alaina’s eyes got wider as she saw this little guy sit on my shoulder, then scamper across the top of my back and leap onto the ground. He disappeared, and I was left feeling blessed indeed.

Encounters like this feel to me like a benediction.

Nature is delivering a message to me that I am in the right place at the right time. For a brief moment I get to experience direct contact – a sort of communion – with a wild animal.

Most of the time wild animals shun humans, and for good reason, if they do not want to get shot and eaten or killed for sport or out of fear. If they do approach, it is often to beg for food or to steal. So a benign encounter is extra special.

Most of the time wild animals shun humans, and for good reason, if they do not want to get shot and eaten or killed for sport or out of fear. If they do approach, it is often to beg for food or to steal. So a benign encounter is extra special.

Two years ago I had a very brief close encounter with a mountain bluebird. I was guiding a tour group and we were walking to a foot bridge over the Firehole River in Yellowstone. As we reached the bridge, something darted out from under the railing. I winced as a bird suddenly flew at me. . .and landed on my shoulder!

Not sure what to do, I froze.

My guests stared in wonder as this bluebird perched on me for a few seconds, then, in a flash of sky blue, it was gone. It seemed to have chosen me, singled me out, for this blessing.

We often regard animals as less than our equals. Matthew 6:26 in the Bible says, “Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they?”

And yet, be they scaly, feathered, furry or finned, these creatures are the manifestation of eons of evolution. They have wisdom we cannot fathom, know things we never knew or have forgotten.

We share with all animals a common ancestor in the vast depths of time. We share the present on this tiny spinning ball in the midst of an immense and indifferent universe. And we share a common destiny, for we all are bound to the same ultimate fate. We ignore and destroy other species at our peril, and in doing so increase our isolation.

As Henry Beston wrote in The Outermost House, “They are not brethren, they are not underlings: they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.”

As Henry Beston wrote inThe Outermost House, 'They are not brethren, they are not underlings: they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.'

Wild animals, too, seek to understand us. Perhaps they choose emissaries from among us, to try to get through our thick skulls that we are one, we are of the same Earth and need to take care of one another. Or maybe these tiny creatures are indeed messengers sent by another, by long passed relatives seeking to reach us from the other side. Perhaps. But this is not fair to the creatures themselves, robbing them of their own volition.

We regard these creatures across a yawning communication gulf. Neither can speak the others’ language. Yet is it so hard to understand the wren? They sing in joy or in rivalry. They court and fight and raise their young just like we do. Birds and animals have many of the same needs as we do, and express themselves in search of those needs.

Surely some bird song comes forth in pure joy, to celebrate new life, possibilities, existence.

Give other species a chance – even the small, obscure ones – and we just might step outside ourselves into a wild and ancient world.

In 2008 Alaina and I backpacked through the Paria River canyon from Utah into Arizona. We tromped down the ever-deepening red rock canyon, repeatedly wading in the shallow, silty river, camping on raised sand bars and soaking up the heat and silence of the Colorado Plateau.

Half way into our forty mile hike we stopped to look around. I set my pack down, when out of nowhere came a small lively bird (a wren?). It landed directly on my chest and stared at me. What! Where did this little guy come from. As quickly as it came it was gone. A mile later we set our packs down again to rest, and I took off my sunglasses for a moment.

A small bird – from all appearances, the same one – landed on the frame of my glasses. Wow. Now I was really mesmerized. What could he want? The bird was so light I hardly noticed the weight. It seemed to look at me.

Hopping off my glasses, the little bird landed on the brim of my hat, turned upside down and looked into my eyes. I was transported. This was nature magic at its best, a visitation from a tiny desert spirit. As my friend flew off, Alaina and I were left grinning ear to ear. Any fatigue or worry that I carried was forgotten.

I don’t buy the notion that humans are extra special or better than animals or birds or fish. We are of the same flesh and bone, made of stardust and ancient minerals and organic compounds, animated by that same mysterious spark of life. Give other species a chance – even the small, obscure ones – and we just might step outside ourselves into a wild and ancient world.