Back to Stories'A Life Lived Wild: Adventures at the Edge of the Map' Is A Great Read

If you are reading these words, then there’s a strong likelihood you savor being in the wild outdoors more than average Americans. So here’s a question that pertains directly to you and your peer group: What do the terms “explorer” and “adventurer” mean in the 21st century when, by using Google Earth, you can zoom virtually into any far-flung corner of the planet from your laptop computer or cell phone?

December 14, 2021

'A Life Lived Wild: Adventures at the Edge of the Map' Is A Great ReadRick Ridgeway has been called 'the real Indiana Jones' for his gravity-defying daring, breathtaking photos and yen to be outdoors. Now his priority is saving what's left of our wild home planet

Review and Interview by Todd Wilkinson

If you are reading these words, then there’s a strong likelihood you savor being in the wild outdoors more than average Americans. So here’s a question that pertains directly to you and your peer group: What do the terms “explorer” and “adventurer” mean in the 21st century when, by using Google Earth, you can zoom virtually into any far-flung corner of the planet from your laptop computer or cell phone?

Does the "Age of Exploration" still exist?

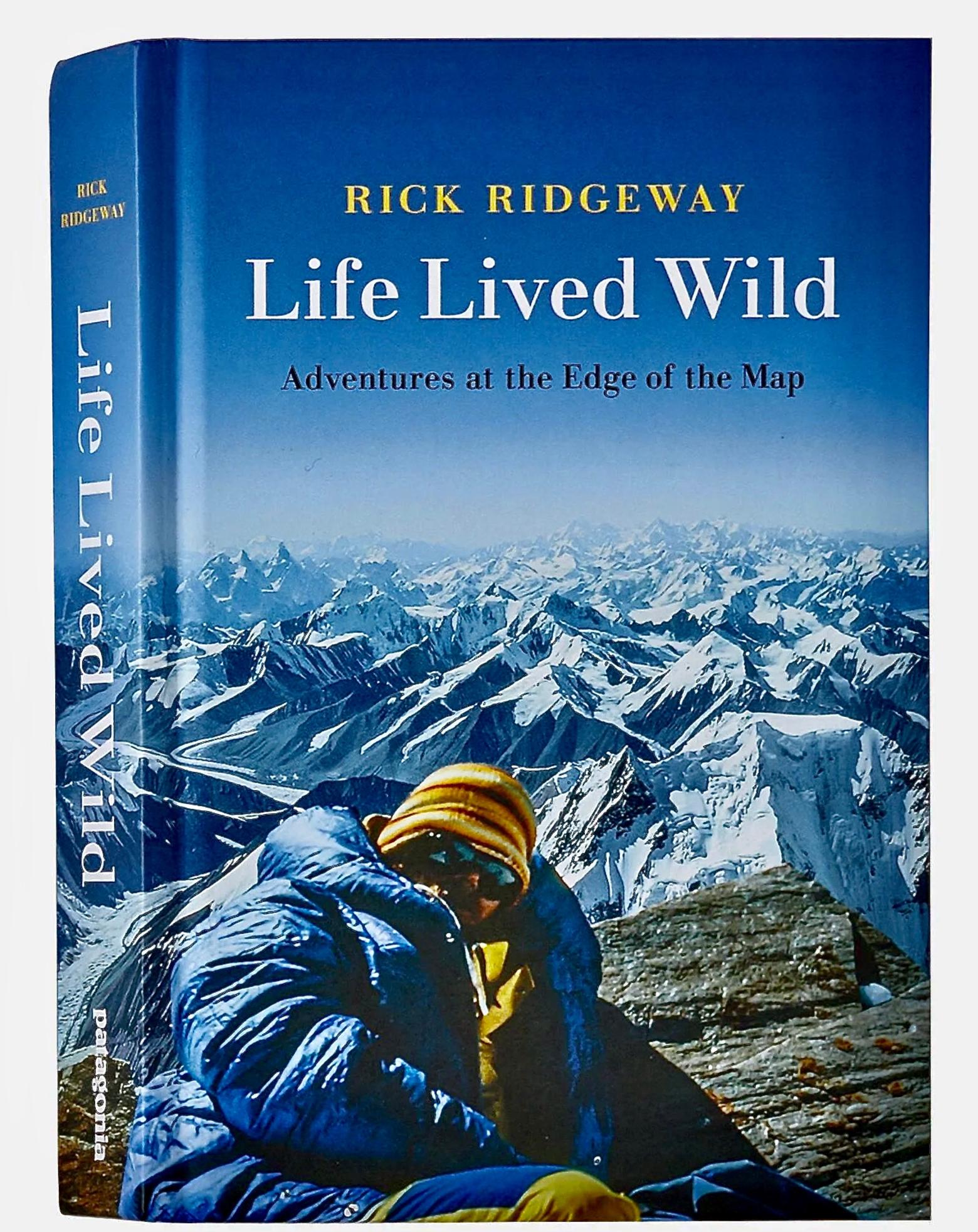

This is an issue that while not residing at the heart of Rick Ridgeway’s provocative and excellent memoir Life Lived Wild: Adventures at the Edge of the Map, it certainly figures prominently as he takes readers through more than half a century of heading (physically, himself) to the most difficult-to-reach places on Earth.

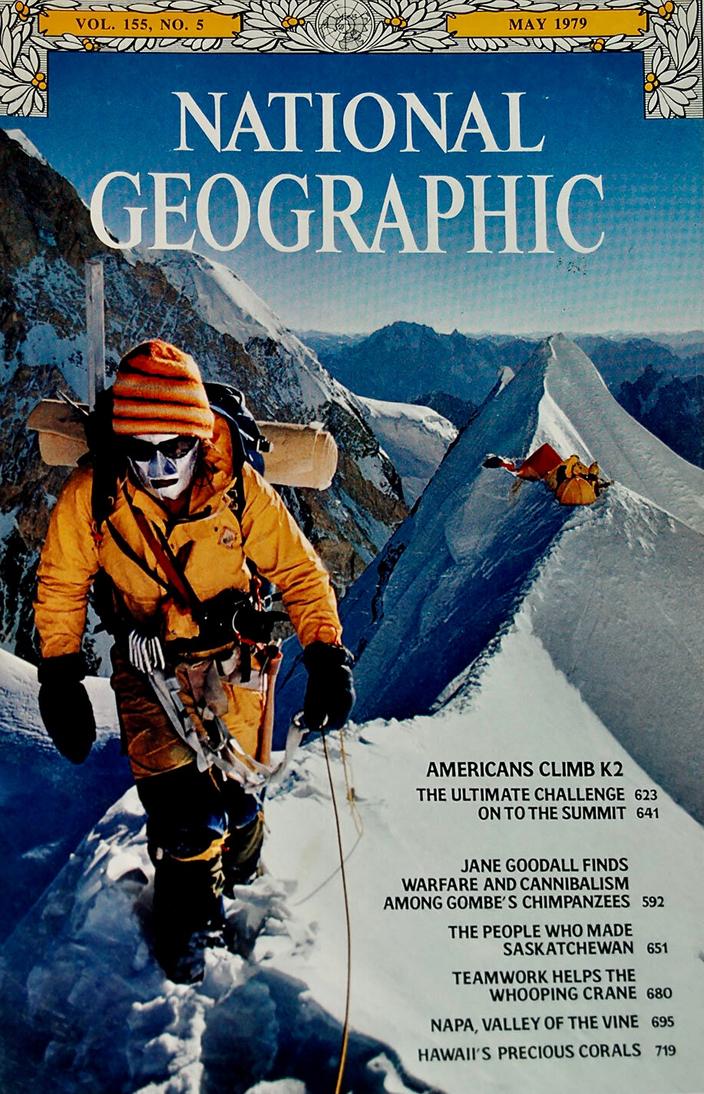

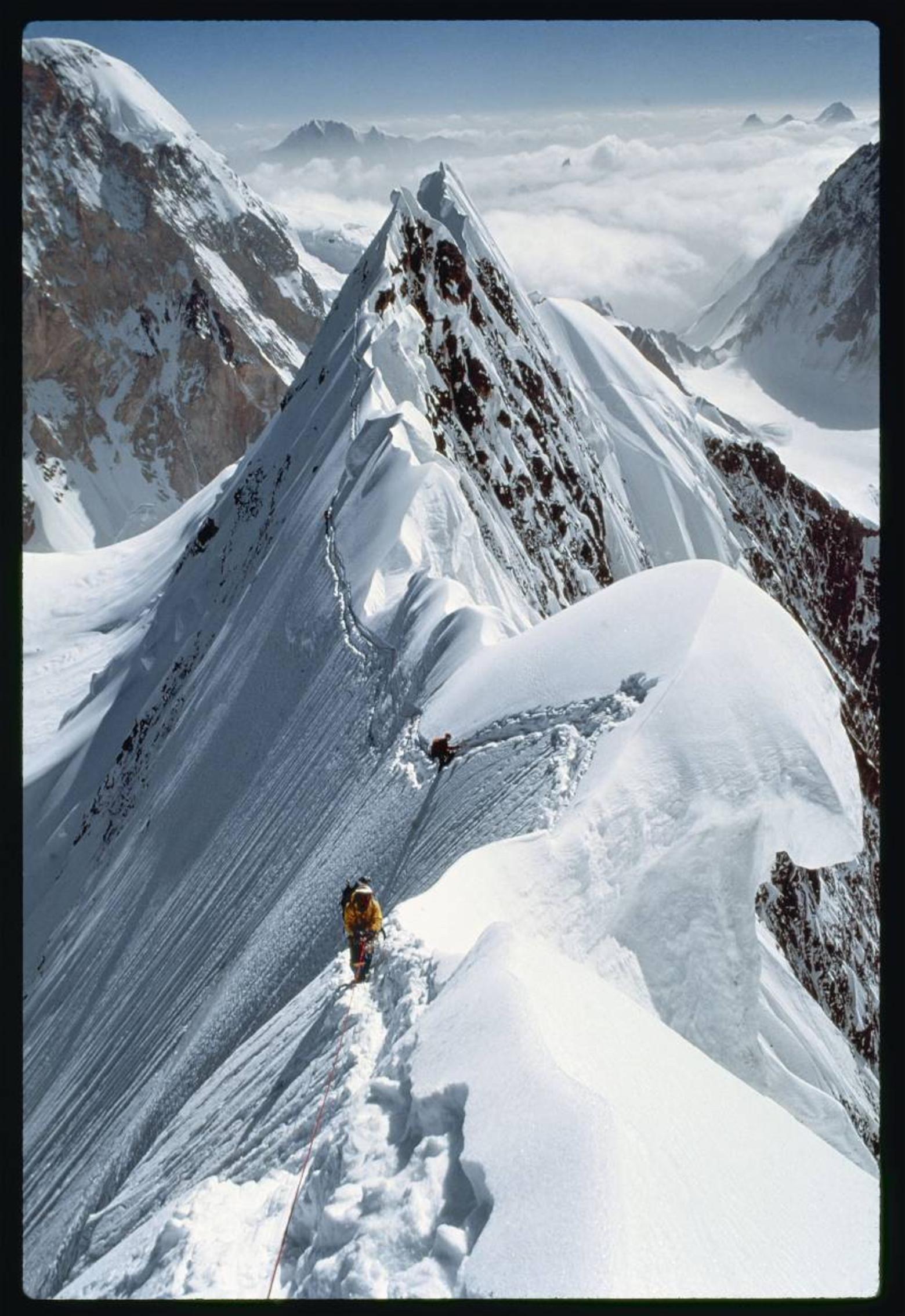

Ridgeway was among the first Americans to summit K2, the world’s second highest mountain at 28,251 feet. He did it without aid of an oxygen tank. Rolling Stone magazine called him “the real Indiana Jones.” He's also the best-selling author of Seven Summits about the attempt of two businessmen, both amateur climbers, to reach the world's tallest peaks.

This is an issue that while not residing at the heart of Rick Ridgeway’s provocative and excellent memoir Life Lived Wild: Adventures at the Edge of the Map, it certainly figures prominently as he takes readers through more than half a century of heading (physically, himself) to the most difficult-to-reach places on Earth.

Ridgeway was among the first Americans to summit K2, the world’s second highest mountain at 28,251 feet. He did it without aid of an oxygen tank. Rolling Stone magazine called him “the real Indiana Jones.” He's also the best-selling author of Seven Summits about the attempt of two businessmen, both amateur climbers, to reach the world's tallest peaks.

Notably, this week he is passing through Greater Yellowstone. He will give a presentation, along with his friend, world-class Bozeman mountaineer Conrad Anker, at the Emerson Cultural Center on Thursday, Dec. 16 and he’ll be delivering a reading at Elk River Books in Livingston on Friday, Dec. 17.

Without delivering a discourse explaining why, let it just be asserted that Ridgeway’s voice matters.

° ° ° °

A few years ago, I was in the company of college students traveling the West on a semester of study. They were learning about issues that shape people, culture, ecology and economy. I was there to discuss environmental journalism and how it is presented to the public.

Among the brightest and most privileged of their generation, the undergrads from Whitman College had a keen interest and understanding of the joys that come from being fit in the great outdoors. Lacking, however, was a kind of ecological awareness; specifically, reflecting on the possible consequences of even the most well-intended people—themselves— moving through landscapes that have managed to hold on to their wild native megafauna.

The Westies were amazingly asute in discussing natural resource extraction issues, and battles between cattle and sheep ranchers and enviros over wolves, and concerns such as winnowing water tables in the West, but engaged in little self-reflection on their own impact.

Curious, I asked them who informs their understanding. Almost to a person the answer was that brand ambassadors of outdoor gear products wielded enormous influence, inspiring them to buy stuff and get outside under the guise that more humans going into more areas to recreate advances conservation.

A couple of the names that popped up instantly were climbers like Bozeman’s own Conrad Anker, his Meru co-star, Jackson Hole part-timer Jimmy Chin, and the spiderman of Yosemite, free climber Alex Honnold. (The students had an expanded list of mountain biking brand ambassadors, skiers/snowboarders, surfers, paddlers, and others representing both differing genders and ethnicities, all sponsored by a suite of well-known product manufacturers).

My question to the group was: “Well, what if the brand ambassadors are themselves not ecologically aware— what if they are not reflecting on the growing impacts of human recreation on the places where they play?” Does expanding recreation access into the backcountry enhance wild places or deplete them?

Often, the conversation at that point would go silent. Such a possibility had never been pondered. Today, the Covid pandemic has brought visitation levels that public land managers didn’t think would materialize for decades to the wildlands of Greater Yellowstone and other parts of the public land West in a very short span. Outdoor recreation has become manifested as a growing industry rather than just a quaint, benign collection of past-times. And, like any industry, its economic health is predicated upon constantly pushing to grow corporate bottom lines and consumer demand for products by fueling appetites to explore and open up more wild places to more people.

But at what cost to sensitive places, especially in a region like Greater Yellowstone that is the only one in the Lower 48 with all of its original mammals that were here 500 years ago and still-healthy wildlife migrations on the landscape? How exactly does promoting more human use and access of public lands secure protection of the spaces wildlife needs to survive?

Enter now a brand ambassador of sorts—Ridgeway— whose resume of feats, photographs, films, writing and indominable grit has inspired generations of young people drawn to extreme and rigorous outdoor adventures. He has credibility.

Invoke whatever spiritual metaphor you like, or think of the allegories of how going to the mountain inspired a change in perspective about life. Ridgeway has been into the attic of the terrestrial world on harrowing climbs, stared across Earth’s oceans as a boater, trekked through deserts, and given us insights from scores of rugged outposts in-inbetween. His bona-fides as a funhog are indubitable.

By his own estimation he’s spent five years of his life sleeping in tents. An amigo both of Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard and the late North Face founder and iconoclastic conservationist Doug Tompkins, Ridgeway was already the prototype of a modern explorer with a camera when current rock stars like climber/cameraman Jimmy Chin was a toddler.

Ridgeway and other legendary figures of the last half century helped popularize an ethos of trying to match one’s body and mental wits against the elements. Lesser known, he has been on the front lines of trying to push a deeper, more urgent ethic of taking personal responsibility for stewardship of a finite planet, both as individuals and corporate citizens.

For 15 years, starting in 2005, he oversaw environmental affairs at the Patagonia clothing company and was sometimes a catalyst for difficult internal conversations about how the brand should promote adventures in the outdoors without encouraging places to become overrun. The mission statement he helped hatch at Patagonia was “Save Our Home Planet.” He’s advocated for making durable gear that does not pollute the environment and harm biodiversity. He's a proponent of re-generative agriculture as it pertains to growing cotton fiber for clothing and raising bison sustainably as a protein product. He also was part of recent soul-searching sessions Patagonia had before it boldly went to the defense of public lands perceived to be threatened by policies of the Trump Administration.

Now Ridgeway has written Life Lived Wild. The book could nott arrive at a better time. The advent of Covid and its variations has set off a crushing, frantic rush to rural and wild America by people seeking a refuge from the city with outdoor-oriented folk looking to check-out or escape.

In its pages, the book not only chronicles the arc of Ridgeway’s path, which is certain to resonate with thrill seekers in places like Jackson Hole, Bozeman and any other mountain town strung along the Rockies; but more importantly, and layered into it, is Ridgeway’s own metamorphosis in pondering the essence of what really matters.

For him, it comes back to embracing full awareness of and striving to live in the moment with people we love, and long before we arrive at a trailhead, realizing that how we approach wild country—whether we are going to become consumers of it—is a choice.

We are proliferating roughshod over planet earth and technology has only increased the pace. Consider social media. Post a pretty photograph of a place that is not on the radar screen of public consciousness, tout its preciousness, then identify its exact location and then you will instantly become a contributor to its destruction.

No good place is anonymous anymore; no good place for grizzlies is safe from being invaded by outdoor recreationists who enter it without humility or regard given to the four-legged inhabitants. Many refuse to confront the paradox that maybe the best gesture we can offer to wildlife is to stay out of its most untrammeled habitat or at least being willing to regulate our numbers?

"In our popular culture there is a maxim that we succeed to extent that we have mentors to guide our passages at pivotal transitions from one phase of our lives to the next," Ridgeway writes. "I was luck y have had that guidance from Doug [Tompkins] and Yvon [Chouinard] and others in our posse. I was also fortunate to benefit from another of our core tenets: it wasn't just doing the adventure sports, it was working to save the places where did the sports."

Ridgeway is an outspoken and unabashed wildlife conservationist, an activist who makes his home in Ojai, California but loves Greater Yellowstone. He even served as a mentor to award-winning nature photographer Joe Riis who has delivered head-spinning documentation of wildlife migrations in the ecosystem for National Geographic.

Rest assured, most of Life Lived Wild involves a recounting of first and difficult ascents where disaster was only a misstep away. The reading is riveting. During his life, several of Ridgeway’s friends did not return alive from a mountain or other form of outing. He watched his climbing partner Jonathan Wright die in his arms following an avalanche in the Himalayas. He also lost one of his dearest friends, Doug Tompkins, to a freak boating accident in Chile on Dec. 8, 2015 and nearly perished that day himself. Not long ago, his wife and soul mate, Jennifer, passed. He devotes high praise to conservationist Kris McDivitt Tompkins, Doug Tompkins' widow and a former executive at Patagonia, for courageously seeing groundbreaking land preservation work to completion in Chile. As he notes, Kris Tompkins has found solace and healing in nurturing rewilding of the natural world.

Ridgeway is at his most vulnerable and powerful in revealing how he copes with the pain of his grief and that of friends. It’s a kind of mourning that applies not only to people but to places. In Life Lived Wild, he is a business-minded brand ambassador earth needs. Publisher's Weekly gave the book this starred assessment: "Perhaps most memorable is Ridgeway’s consistent sense of wonder at nature: 'the beauty of the untamed world... had become a foundation for all our lives.' Readers will be left in a similar state of awe."

A short while ago, Ridgeway and Mountain Journal had the exchange below.

TODD WILKINSON: I came of age as one of the many minions who were grateful to you for taking us on vicarious adventures, for heightening our sense of awe, wonder and dreaming. As you look back now, what would Rick Ridgeway tell his younger self that he needed to know in his twenties?

RICK RIDGEWAY: From what I know now, I think I would have told my younger self to think less about my ego driving my ambitions to achieve the goals and the sports and expeditions that I tackled. And to focus more on the process instead of the end result. And that's why I chose to start the book with the Everest expedition in 1976, my first trip to the Himalayas, one of the first major climbs of my career. I challenged myself in the retelling of the story to confront my real motivations for going on a trip, for being so focused on reaching the summit. And looking back on it now I would have been wiser in my younger years had I focused more just on the adventure itself, on getting out each day when I could, but that's not to say I didn't do that.

TW: You write about how you were humbled by the beauty and diversity of the terrain and heartened by the people of the high Himalaya.

RIDGEWAY: I was fascinated by the culture of the Sherpas. Each day I was with them, I tried to learn more about them. I was thrilled with the chance just to be in the Himalayas, with the flora and fauna. I've always been drawn to birds and I loved the chance to witness some of the wildlife in the Himalayas. And then the climb itself, just to be there on a daily basis, unless there was a storm, to witness the beauty of my surroundings. But still, my goal to reach the summit tended to overarch and sometimes even displace those more day-to-day experiences. Looking back on it now. I would have paid more attention to that. That's why in my new book, I say one of the things I've learned over my life is that the goal isn't the summit. It's the footsteps to get there.

TW: As you look back and ponder the size of the earth you encountered when you set out to explore it, and how you measure it today, what’s your assessment?

RIDGEWAY: It is smaller now. And the reason is that there are so fewer places now that are still unknown. When I was in my teens and 20s, just starting out as an adventurer, there were so many places on the planet that truly seemed off the map. Where few explorers had been, where there was little information about what actually might be there, and my imagination was left to fill in the blanks. I think now that there aren't any more blanks, that there are fewer unknowns, the result is that the planet does feel smaller. And some of it too, I suppose, is just the fact that now in my 70's, I've seen so much of the world that I have a sense of its size, that's pretty visceral. And I have direct knowledge of so many of its places that it does seem, in some ways smaller. But at the same time, there's one part of it that's the same.

TW: And that is?

RIDGEWAY: The sense of just the size and mass of our planet. That feels the same as it did when I was a kid. And that's because especially when there's a full moon that you can watch rising over a ridgeline. You can actually see the moon as it rises. You can see the speed of the Earth as it is actually turning. Because, of course, it's not the moon that's rising, but rather it's the earth that's spinning giving the appearance that the moon is rising. And if you are by yourself. without others around to distract you so there's no other conversations to track from your attention, if you watch closely, the moon rising above that red line on a full moon night, imagine that it's actually the earth spinning, and you can feel the speed of its spin.

TW: It sounds like a sense of awe that has only deepened.

RIDGEWAY: When you have travelled around the globe enough to have a sense of its size, that you get into your bones a sense of this mass of this planet, slowly turning and that allows you to project yourself beyond the planet itself and to kind of wander out into the solar system and even beyond it. When I do that in my mind, then the place is just as big as it was when I was a kid.

"Towards the end of my younger years, my life became dedicated to saving those few remaining wild places on our planet. I realized the arc of my life has been a long and continuous evolution from going on adventures in these wild places to saving these wild places. Reflecting on that arc, I realized part of it was the growing awareness of climate change and with me, it wasn't a removed awareness but an awareness directly connected to bearing witness to climate change."— Rick Ridgeway

TW: You write with veneration for local people living in the remote places you reached and note that in terms of exploration, it involved Westerners not discovering them but entering places known to the native denizens.

RIDGEWAY: I think what most distinguishes the era of mountaineering in my life was that we were able to get into some of the few remaining wild places on the planet that had been visited only by a handful of outsiders, if ever. In that sense we were at the end of the Age of Exploration that really started 500 years earlier when people from Western cultures started venturing out into the unknown parts of the planet that were of course already known to the indigenous people living there.

I'm talking about the discovery by Western culture and Europeans and American descendants of Europeans into the rest of the planet. In some ways it carried all the way into the last part of the 20th Century when there were still a few places that hadn't really been explored. Like that area in Tibet that Jimmy Chin, Conrad Anker and Galen Rowell and I traversed on our Chang Tang expedition. No westerner had been there before. By then the terrain had been photographed in landsat photographs. In that sense, our on the ground exploration was a little past the Age of Exploration.

TW: It seems like the Age of Exploration and what preceded it held more mystery because there was no device ready at hand so that a person who got into trouble could easily call for help and get a helicopter rescue. I.E. more self-reliance than reliance on gadgets that can not only avail a button push to 911 but turning intimate personal moments in the outback into almost instant shareable events on mass media.

RIDGEWAY: The real end of it [Age of Exploration] was in the previous generation to mine. In my book, I tell the story of Lincoln Ellsworth flying his plane across Antarctica to the South Pole, crossing an area of the continent that no one had ever seen before. He got into a whiteout and climbed higher and higher. He knew that even if he could get the plane to 30,000 feet, he might not be safe because he had no way to know if out in front of him, there might be a mountain higher than Everest. So just imagine that. That was in the late 1930's. And he didn't know if there was a mountain on the planet higher than Everest. That meant that there were still parts of the planet completely unknown. Within a few years after that, that was no longer the case. Those of us going out into the wilds of the world in the '70s and '80s still had a chance to put a last footnote into that last chapter of the Age of Exploration.

TW: Your book is different from being a mere chronological recounting.

RIDGEWAY: As I wrote my new book, Life Lived Wild, I reflected on my adventures and expeditions. In its first draft, it was just that—a collection of separate stories about adventures and expeditions. There were too many stories that were wanting to be a memoir and they weren't. So to rewrite the book into a memoir, I had to reflect on the stories and through that reflection think about my life more deeply. In that process, I realized that in the beginning of my life of adventure in my 20's and 30's, it was really about the adventures. The climbs and the explorations and the people and friends I went with and met. The excitement of going to the wildest places in the world.

TW: That same sentiment is certainly shared by young people today. You, however, speak to not only a shift in values, from being focused on self to pondering the power of self-restraint. The way you present it comes across as an opportunity for younger readers to reflect. You seem to basically be saying a person doesn’t need to wait until middle age or older to defend the last shreds of wild Earth.

RIDGEWAY: Towards the end of my younger years, my life became dedicated to saving those few remaining wild places on our planet. I realized the arc of my life has been a long and continuous evolution from going on adventures in these wild places to saving these wild places. Reflecting on that arc, I realized part of it was the growing awareness of climate change and with me, it wasn't a removed awareness but an awareness directly connected to bearing witness to climate change. Actually seeing in human time changes that were normally measured in geologic time. That realization had an enormous impact on me.

TW: You’ve actually seen it happening on a mass scale with how the impacts of climate change are coming fast to the poles and mountainous places.

RIDGEWAY: When I began to see glaciers that in my youth were much larger than they were 20, 30 and 40 years later, I could actually see and witness the retreat of the planet's ice. Having dog mushed down the Larson Ice Shelf, I read in The New York Times that large sections the size of Delaware were breaking off in some of the world's largest icebergs ever recorded, floating into the ocean and melting. Huge shelves of ice where I had been on skis and traversed on foot. That had an enormous impact on me.

TW: It goes far beyond your pondering loss of recreational opportunity in the future. You see wild places—untrammeled places not overrun by people—as being essential to resiliency and our ability to not only withstand things like water challenges but preventing the loss of other beings that depend on wild country to survive. To us at Mountain Journal, there has been a major disconnect between the so-called outdoor recreation community seeking out wild places for pleasure and understanding their vulnerability, fragility and supreme importance as habitat.

RIDGEWAY: From a cerebral level, studying the issue more, I began to realize that we Human Beings are facing two incredible existential crises: the climate crisis and the extinction crisis. They're not the cause of the problems that we're facing. The real cause of those two crises are too many people using too many resources on a planet that has limited resources to support Humans. If we continue on this path, the planet will simply not be able to support us. I had a commitment to saving wild places that was coming from direct experience as well as what I was learning from my reading and research. Those two things combined made me commit to doing something about it.

TW: You’re using your standing not only to serve as a wake-up call but bringing members of your own tribe—outdoor adventure seekers and conscientious companies— into a conversation they may not really want to hear.

RIDGEWAY: I often like to quote my friend Yvon Chouinard who reminds us all that we all need to do something. That we all need to pause and reflect on what we're good at. What tools do we have in our boxes that we can use to do something about this? He says if you're a good writer, you have to write about these issues. That's what I'm doing. If you're a good speaker, you have to speak out about them. I do some of that too. If you've got free time, you should volunteer to do something about it. If you've got extra money, you should donate to the groups on the ground fighting to save our wild places and through that, to save our home planet, and through that to save ourselves. But the key is that it's only going to make a difference if each of us does something.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Enjoy the short video below in which Ridgeway talks about losing his favorite climb to climate change. Full disclosure: Patagonia Books published Ridgeway's memoir. The philanthropic arm of the company also has been a supporter of MoJo's environmental reporting.

HELP US BE MORE, DO BETTER: Mountain Journal brings you stories you won't find anywhere else! What's the value of that in your life? Please consider supporting us by participating in the NewsMatch program available to journalistic non-profits creating content in the public interest. We profoundly appreciate your generosity in helping us protect the Yellowstone region with facts. You can do that by clicking here. Every contribution, up to $1,000, will be matched dollar for dollar!

Make sure you never miss a a story by signing up for Mountain Journal's free weekly newsletter. Click here: https://bit.ly/3cYVBtK