Back to StoriesWe Are All Connected

March 29, 2024

We Are All ConnectedFinding unity, elegance and bliss in the wild

by Susan Marsh

To connect—whether with

people, wild nature, or a work of art—invites an opening into bliss. Bliss: it’s

a word I don’t often use to describe my state of mind. Delight, enjoyment,

contentment, yes. Often. But like awe, bliss arrives rarely, unbidden and

unexpected. Joy bubbles up from inside as a reaction to a pleasant experience,

but bliss feels as if it comes from far beyond the self.

As suddenly as bliss fills

me, it begins to fade, leaving an enduring palimpsest underlying the hours and

days and years that follow. Moments of bliss live in memory as times when my solitary

self became deeply connected to the greater whole.

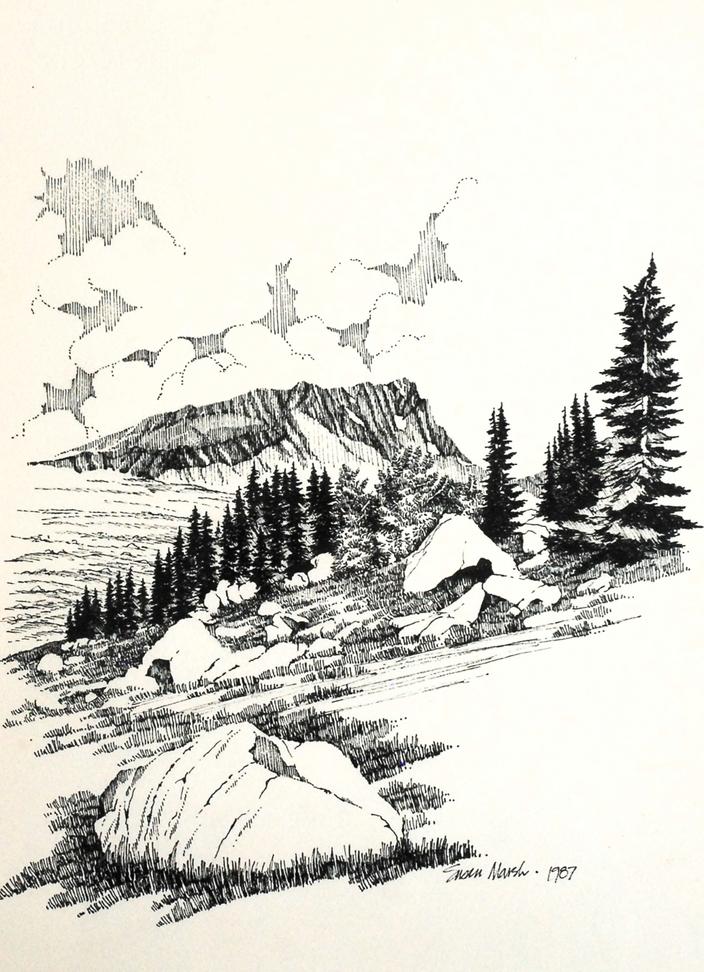

Very few occasions are so

memorable. One of them happened while I was on a backpacking trip in the mid-1980s.

After organizing camp and cleaning dinner dishes, I wandered out beyond the

shelter of stunted firs near an alpine lake. In the cirque basin, outcrops of

glacier-polished granite intertwined with low willows and mountain heather. A deep,

narrow creek meandered around black-moss boulders, already settled into evening

shadow, while the upstream lake and high peaks surrounding it were lit with

gold from the late-day sun.

All at once, bliss poured

into me. I forgot myself, one lone human figure stepping across granite slabs. I

merged with the rocks and each low rattle of creek water, each bit of sun gleaming

against the side of a cliff, each thick-leafed twig of mountain heather. Together

we were gathered into the warm woven threads of the all.

I struggle to put this sense

of connection and completeness into words that come close to suggesting how it

felt. It’s easier, I believe, to say what an experience of bliss is not. It’s not

exuberant joy, the way I feel skiing deep powder on a cold sunny day, or

reaching a summit from which miles of mountains spread in all directions. It

isn’t wonder, which I feel under a sky full of stars or watching a moth emerge

from a cocoon.

I might describe bliss,

perhaps counterintuitively, as a dampening of self-awareness and cognition. My

awareness expands to encompass what surrounds me in a way that leaves behind

mere thoughts, words and explanations.

Moments of bliss live in memory as times when my solitary self became deeply connected to the greater whole.

This feeling might be similar

to what saints and mystics describe in their writings, a sense of being one

with God. It might be a slight suspension of my physical and temporal

existence, one of those cracks that let the light in. All I can do in words is

describe the feeling with metaphor, for the gift of bliss is ineffable.

I contrast the bliss I felt on

one summer evening in the high Absarokas to a walk along the ocean shore on a winter

night. I followed the narrow and changing strip of not-quite land and not-quite

sea, where the sand was wet and solid underfoot, where the sound of the waves seemed

to pound from all directions.

The experience was memorable,

but neither singular nor one of bliss. The ocean asked for an empty and contemplative

state, neither sad nor joyful. It asked for the kind of attention that is best

given in solitude, in winter, at night. I felt more like a witness to the power

and immensity of the sea than an integrated part of it. I am a land mammal,

after all.

Beyond a fundamental

connection with wild nature, among our deepest is with music. First you hear

it, then you become conscious of the sounds. It might draw you in. You stop,

listen. If you love what you’re hearing, you invite it in. Perhaps it’s a piece

you recognize, remembered from youth or last summer’s concert. You find

yourself humming while doing the dishes. You coexist with the music, deepening

your connection.

I suppose our greatest

connection to music comes by playing it. You are creating the thing you love. A

rare few are able to compose, much to the delight of the rest of us.

This can happen with any

kind of art, but music is an art form that lives in the air we breathe. It is

perhaps the oldest of the arts, predating humanity as birdsong, thunder, the

sound of moving water.

I might describe bliss, perhaps counterintuitively, as a dampening of self-awareness and cognition. My awareness expands to encompass what surrounds me in a way that leaves behind mere thoughts, words and explanations.

Some art can be enjoyed in

solitude, but music—and its close cousin, dance—creates an atmosphere of

community. Music exists in all cultures, an innate part of being human. Rhythm,

percussion, heartbeat, earth beat, bringing in all to become one under the same

tempo.

I’ve been playing piano

lately after decades away from a keyboard. I find, to my disappointment, that I

have as much trouble reading the notes for both hands simultaneously as I did

when I was taking lessons as a child. But I find to my pleasure that I can still

pick out a tune without reading the music sheet at all.

I think this means that

music inhabits me. My brain forgets, my fingers remember, and my ear tells me

how I’m doing. It’s physical instead of thoughtful, like the bliss I find in

the mountains.

One reason music strikes me as different

from other art is its airborne physicality. Paint, clay and charcoal are

physical as well, being made of earth and its products. But they seem to remain

inert—a damp lump, a cracked scrape of dry pigment, a charred stick—until I

pick them up to make something. Musical notes seem to come alive from out of

nothing when a vibration begins, formed by sound waves with specific

frequencies traveling through invisible air.

It’s like magic, but science tells us

it’s real. The wave lengths, amplitudes and frequencies of all kinds of

radiation, light and sound are phenomena of nature; how the universe works.

Just how the universe works can be partially

described in the language of mathematics. If dance is music’s cousin, math is

music’s twin. I recently finished reading, or rather meditating upon, Alec

Wilkinson’s A Divine Language, in

which he describes mathematics as something humans discovered, rather than

invented. He suggests that math is evidence for a universal intelligence.

This idea put a puzzle piece into

place for me.

As a child, I spent the majority of my

free time in the woods adjacent to my parents’ house, accompanied by the trees

I climbed and talked to, the native blackberry vines that bore the most

delicious fruit, and the birds and small animals that still lived in that 10-acre

woodlot surrounded by a growing suburb. The red ants, upon whose nest I sat as

a poorly considered experiment at age 4 or 5, accompanied me home one day as

well. There was also a presence I felt in

those woods—gauzy and nebulous, without a name.

Wilkinson writes that he felt

something with and beyond him as a child, an undefined presence. Perhaps

children are better tuned into such things than distracted and busy adults, but

I could strongly relate to his experience, even now. It is the source of bliss. My nameless sense of something beyond

me now seems to have a stronger foundation. A foundation made of concrete. Or

maybe mathematics.

The child I was had a rudimentary sense

of the unity, symmetry and elegance of all things. I took that sense into

adulthood, and decades later I am somewhat better at articulating it. It is a

comfort to feel that I, and each of us, can be part of the unbreakable connections

in the universe.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Mountain Journal is the only nonprofit, public-interest journalism organization of its kind dedicated to covering the wildlife and wild lands of Greater Yellowstone. We take pride in our work, yet to keep bold, independent journalism free, we need your support. Please donate here. Thank you.

Related Stories

January 16, 2024

In Cadence: ‘Mni Wiconi’ and the Great Observers

Recalling the 2016 Standing Rock demonstrations protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline, a Lakota woman reflects on the rhythm and power of...

November 22, 2023

The Arrival of Harriman’s Iconic Trumpeter Swans

By the early 1900’s trumpeter swans were nearly extinct, but concerted efforts have reinvigorated their numbers. Land around Harriman Ranch State...

December 13, 2023

Ecocentrism and Anthropocentrism: Where do we Stand in Greater Yellowstone?

In this guest essay, Clint Nagel examines two world views of humanity’s role on planet Earth. And says the time to...