Back to StoriesMaintaining Forward Progress With The Great Bear

September 15, 2020

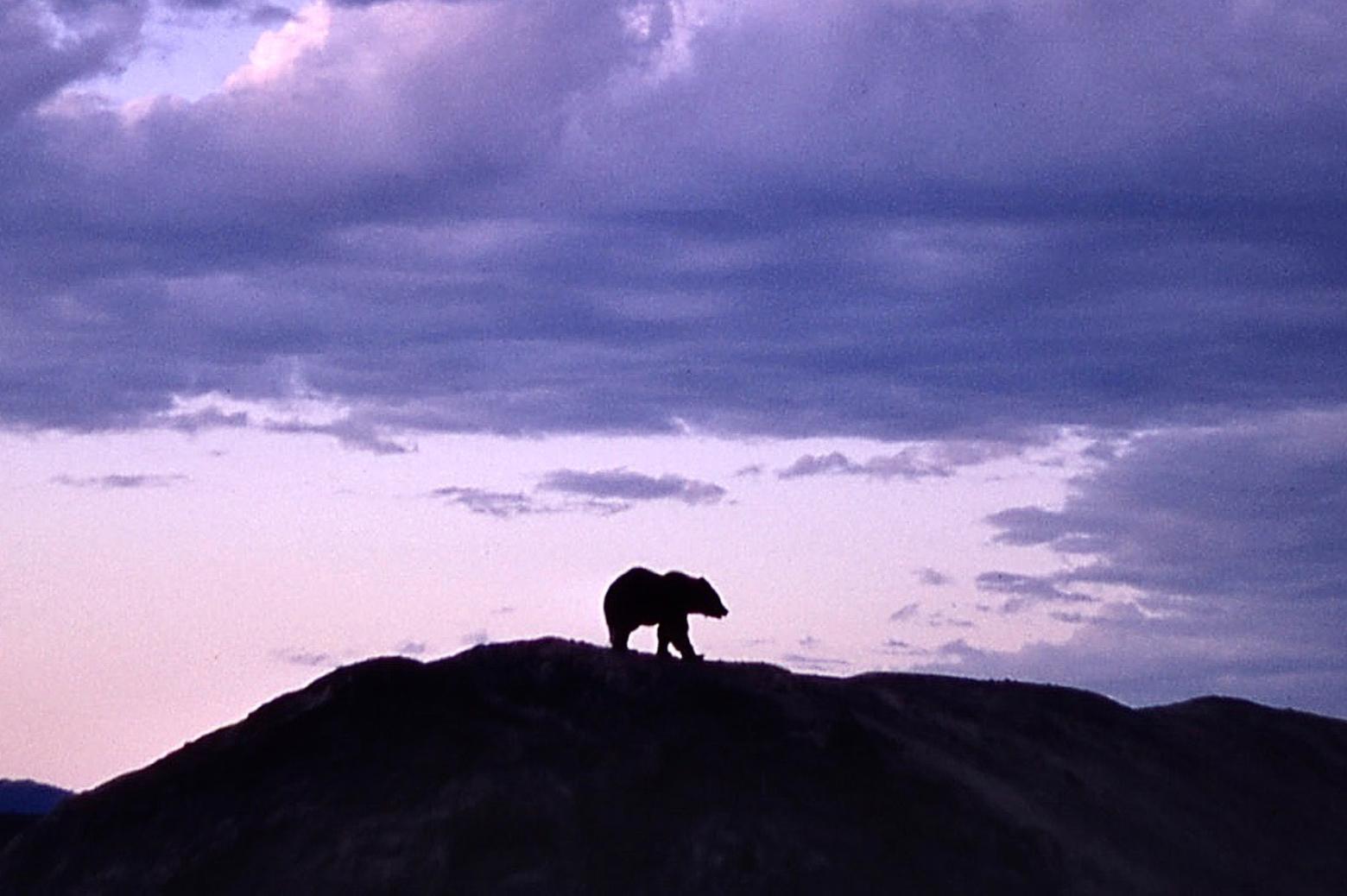

Maintaining Forward Progress With The Great BearRandy Newberg is host of some of the most popular hunting shows on social media in America. He reflects on stalking wapiti in grizzly country and Montana's strategy for guiding bruin conservation

by Jessianne Castle

Randy Newberg doesn’t carry a sidearm. Clocking some 100 days every year exploring the unbound—and often bear-laden—pockets of the American landscape, Newberg says when it comes to a bear attack, he’d leave his trust in an aerosol rather than a piece of lead.

“I’m really proud that Montana is one of the places that grizzly bears have always been. It’s an example of the conservation ethic in Montana,” he says.

It’s a personal decision, one that

is the right of each individual who steps foot in the woods, but for Newberg,

carrying bear spray is a no-brainer.

Newberg is a hunter who calls

Bozeman, Montana, his home. He is the producer of two popular TV shows, “Fresh

Tracks” and “On Your Own Adventures,” as well as the Hunt Talk Podcast, where

he advocates for sportsmen and public land access.

The first time Newberg encountered

a grizzly bear at close range, he says drawing a sidearm, aiming, and then placing

an accurate shot would have been near impossible. He was on an archery elk hunt

in Southwest Montana, full of anticipation after spotting a herd of cow elk. As

he crested a small hill, he came head-on upon a boar grizzly, maybe 12 yards

away.

Fortune looked kindly upon

Newberg—the boar turned and hoofed it after realizing Newberg was there. “He

covered ground so fast,” Newberg says. “If he would have decided to come toward

me, he would have been on top of me so quickly. I wouldn’t have been able to

arm myself. I now have no false ideas that I’m going to do some John Wayne or

Clint Eastwood thing on a charging grizzly bear.”

Carrying bear spray is one of a

handful of behaviors that have become customary for Newberg as he ventures into

areas that are home to grizzly bears. Newberg chooses to take these precautions

out of a sense of self-responsibility for the conservation of grizzly bears and

he hopes other people who find themselves in bear country will consider taking

proactive steps as well.

Our behaviors and choices all play

in to the larger picture that is the future of grizzly bears in Montana. And a

future that is bright for both grizzly bears and people depends on the actions

of local communities, businesses, nonprofits and individuals.

The essential role of stakeholders

is emphasized in the work of the Montana Governor’s Grizzly Bear Advisory

Council and its newly released recommendations for how wildlife officials

should manage bears. These recommendations, released on Sept. 8, will provide a

starting point for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks as the agency drafts a new

statewide grizzly bear management plan that will address grizzly bears as an

endangered species and their management after delisting.

Choices

Newberg, 55, has called Bozeman

his home for almost 30 years. It’s a burgeoning place today, but one nestled in

a microcosm of the Rocky Mountains, an area ripe with elk country lore. But the

heavy timber and robust forage of good elk habitat is excellent grizzly bear

habitat too.

The first night Newberg spent

camped out in thick griz country, every sound was amplified. Snapping sticks

from a winter-ready squirrel or the rustling of leaves on a cool breeze

triggered an immediate worry: What was that? Was that a bear?

“I want to hunt elk, so I had to

figure out how to get over fears about grizzly bears,” he says. “For me that

meant learning all about grizzlies so I can avoid conflicts. The more you know

about bears, the easier it is to avoid them.”

“I want to hunt elk, so I had to figure out how to get over fears about grizzly bears. For me that meant learning all about grizzlies so I can avoid conflicts. The more you know about bears, the easier it is to avoid them.” —Randy Newberg

Hunting poses an interesting

complication in bear habitat: in order to successfully pursue game, hunters

travel quietly, often at daylight or dark. This is contrary to the typical

bear-safe recommendations: hike in groups of three or more; avoid hiking at

dawn, dusk or at night; make noise; stay on maintained trails.

Newberg shared his thoughts about

how to safely hunt in grizzly bear habitat during a July episode of The Elk

Talk Podcast with Corey Jacobsen. Among other points, Newberg told Jacobsen that

by knowing bear behavior you can better predict where bruins might or might not

be.

For example, in the steep,

furrowed mountains of the Madison Range, during Montana’s September archery

season, grizzly bears are likely at high elevations eating army cutworm moths

that feed on the nectar of alpine wildflowers by night and rest under rocks and

boulders by day. Also, grizzlies could be congregated on north-facing, brushy

slopes still abounding with huckleberries. Knowing these two things, a hunter

could reduce his or her likelihood of stumbling upon a bear by avoiding the high-density

areas: high, rocky elevations and brushy north slopes.

He added that if the spot you plan

to elk hunt is especially bear-dense, it could be worth it to hunt earlier in

the season—such as during September archery or the beginning of rifle season in

October—when bears are still looking for moths and berries, as opposed to later

in the season when they’ve started scavenging on hunter-killed carcasses and

are getting ready to den in late October or November.

Another scenario unique to hunters

that is also a high-risk setting for bear encounters is during animal processing.

“Getting an elk down on the ground in grizzly bear country is the hunter’s definition

of mixed emotions,” Newberg told Jacobsen. There’s a great sense of excitement

and accomplishment, as well as the realization that you now have to process the

animal, spending time focused on gutting and preparing what has already become

a bear attractant.

Newberg prefers to hunt with another person that way one can gut, carve and cut, while the other keeps an eye out for bears. They’ll haul the meat a couple hundred yards from the carcass for processing, and if they have to make trips in order to pack it all out, they always hang the meat away from the carcass in a place they can clearly see as they approach on the return trip.

“There are lots of things you can do to lower your risk, but there is still always the risk,” Newberg told Jacobsen. “Even if you do all of the right things you could still have an encounter or just bad luck.”

But for Newberg the risk that comes with having grizzly bears is a part of what makes Montana the special place that it is. “When you use the natural world as your grocery store, you grow to appreciate all the animals,” he tells me over the phone. It’s a couple weeks after Newberg and Jacobsen recorded their podcast, and just a month before the Treasure State’s opening day of archery.

“I’m really proud that Montana is one of the places that grizzly bears have always been. It’s an example of the conservation ethic in Montana,” he says.

Changes

In 1975, with some 800 to1,000

grizzlies remaining in the Lower 48—down from an estimated population of

50,000-100,000 prior to the 19th century—the U.S. Fish and Wildlife

Service (USFWS) listed grizzlies as threatened under the newly-created Endangered

Species Act..

The decades of robust conservation

efforts that followed affirmed the public’s commitment to preserving grizzly

bears. Albeit a slow journey, the distinct grizzly populations near Glacier and

Yellowstone National Parks—known as the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem

(NCDE) and Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE)—steadily grew in health and

number and by the year 2000, the public heard rumblings of delisting.

The Fish and Wildlife Service—the federal agency

responsible for the oversight of listed species—sought delisting of the

distinct GYE population in 2007 and 2017, however several groups sued the

agency and federal courts overturned the delisting rules over fears of

prematurity. Litigation has continued in offices and courtrooms, meanwhile on

the ground in Montana, Wyoming and Idaho, communities and wildlife managers are

wrestling with the challenges that come with more people and more bears in some

areas and dwindling bear populations in others.

Currently grizzly bears are

managed in the Lower 48 with an interagency, multi-state approach that includes

oversight from the Fish and Wildlife Service and field support from the state wildlife departments, US Forest Service and US. Geological Survey, which oversees the Yellowstone Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team.

The silvertip was listed on the

Endangered Species List under six distinct populations—six areas bears were

known to still exist in 1975. These are the Greater Yellowstone, Northern

Continental Divide, Bitterroot, Cabinet-Yaak, Selkirk and North Cascades

ecosystems. Today, USFWS reports there are an estimated 700 bears in Greater Yellowstone, 1,000

in the Northern Continental Divide, maybe 50 to 60 in the Cabinet-Yaak, and 70 to 80 in the Selkirk. There is not yet a resident population of grizzlies in Montana and Idaho’s Bitterroot Ecosystem or

Washington’s North Cascades.

In 2000, then governors Jim Geringer

of Wyoming, Marc Racicot of Montana and Dirk Kempthorne of Idaho convened the

Governors’ Roundtable on the Yellowstone Grizzly Bear Conservation Strategy.

This roundtable comprised of 15 citizens, five each from Montana, Idaho and

Wyoming, who were charged with thoroughly reviewing an interagency draft of

what is known as a “Conservation Strategy.” This document guides conservation

and management actions upon delisting for bears in and around the Greater

Yellowstone.

At the time, former Director of Fish Wildlife and Parks Patrick Graham said, "Bears do not recognize political boundaries. That’s

why Idaho, Montana, Wyoming and the federal land management agencies must work

together."

Newberg was among those 15

individuals who were appointed to develop the plan. “I look at the amount of

changes, how much change of their daily lives Montanans agreed to,” he says,

describing a cease in timber sales, grazing allotments and motorized use in

core grizzly habitat. “This happened because people said they would be willing

to make changes. That was a generation ago. It was a huge part of what allowed

grizzly bears to recover as they have today. The amount of sacrifice that the

citizens of Montana, Idaho and Wyoming have made should not be forgotten.”

Commitments

“Grizzly bears are valued by

people and cultures across Montana and around the world,” Montana Gov. Steve

Bullock wrote last year. “Grizzly bears are also feared and can affect people’s

livelihoods and safety. … Grizzly bear numbers in Montana continue to increase,

and have expanded into areas where they have not been for decades, including

places key to connecting their populations. … Existing management plans did not

fully anticipate grizzly bear distribution across the landscape and as

Montana’s human population continues to grow, we can expect conflicts between

bears and people to increase in frequency and complexity.”

These words begin an Executive

Order calling together a citizen panel that was tasked with creating a vision

for grizzly bears across the entire state. In July 2019, Bullock appointed 18

members from more than 150 applicants to sit on the Governor’s Grizzly Bear

Advisory Council, which met monthly between October 2019 and September 2020 in

order to discuss current conservation measures and community challenges then

draft a series of recommendations that will guide Fish Wildlife and Parks as they look to

develop a statewide bear plan.

On Sept. 8, the council released

recommendations that provide guidance on how the council would like to see FWP interact with bears. Specifically, these recommendations consider topics

like public education, conflict prevention and response, bear distribution, and

funding. They include the council’s thoughts on a possible grizzly hunt if they

are delisted, and recommend funding priorities. Look for a story soon in Mountain Journal on what the council recommended.

Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks Director Martha Williams says

this statewide approach is an important step in continued grizzly bear

conservation—at a time when bears are beginning to expand into areas outside

the original recovery areas—as the conservation strategies deliberately leave

for each state the discretion to prioritize and enact goals for attaining

healthy and sustainable populations of grizzlies, provide for human safety, and

minimize impacts to people’s livelihoods.

“As bears move to new areas, they

also move into areas that contain more private lands or communities,” Williams

says. “Regardless of whether the grizzly bear is listed and covered by the Endangered

Species Act or not, we all have a responsibility to understand what is needed

to help people and bears, and take actions to help both. We at MT FWP recognize

that a robust public engagement process helps inform a thoughtful approach to

grizzly bear management. It does not replace science, as science informs and

serves as a critical foundation to our actions. Yet, much of grizzly bear recovery

centers on conflict prevention, conflict reduction, and information, education

and outreach. Those require working with people and communities.”

“Regardless of whether the grizzly bear is listed and covered by the Endangered Species Act or not, we all have a responsibility to understand what is needed to help people and bears, and take actions to help both. Much of grizzly bear recovery centers on conflict prevention, conflict reduction, and information, education and outreach. Those require working with people and communities.” —Martha Williams, director of Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks

Throughout the council process,

members have worked hard trying to explain their personal values and experiences

while also hearing and understanding the values and experiences of other

council members. Their process was guided by Heather Stokes and Shawn Johnson,

social scientists from Missoula’s University of Montana. Unique from many other

working groups, this council chose to not only lead their own discussions, but

also appoint a member-derived writing team that drafted their recommendations,

as opposed to relying on agency staff.

“I am immensely grateful for the

difficult, inclusive and intentional conversations the Grizzly Bear

Advisory Council took on,” Williams says. “They poured their hearts and souls

into their work. They clearly cared and they put the time and effort in to

develop big-picture guidance and actionable recommendations for the Governor,

Montana and ultimately MT FWP.

“How lovely is it to see a group

of committed individuals with widely disparate views come to respect each other

and not only respect where each is coming from, but take on the hard and

uncomfortable work of trying to figure out how to move forward, where to go,

how to guide Montana in this important work?,” she adds. “I’d argue Montanan’s

have done this time and time again, and how grateful we can all be for those

individuals willing to roll up their sleeves and take on a task that can be

thankless. Yet, it’s how we do our best work and work that is needed.”

Newberg recalls the challenges of

working together to find solutions—there were controversial issues the

Governors’ Roundtable had to work out 20 years ago. But he says it took

reasonable people who were willing to see issues from another’s point of view.

It required talking, a willingness to become vulnerable, and deep respect and

trust. And tackling those hard issues still requires those things.

“When people sit at the table,”

Newberg says, “you know they want to be part of the solutions. If you care

about wild places and wild things, you get satisfaction that Montana is still a

place where bears can be. Regardless of delisting, I think Montanans can be

proud that we’ve always made space and accommodation for grizzly bears.”