Back to StoriesLetting Go Of My Big Sister

June 22, 2018

Letting Go Of My Big SisterAging in America sucks, says Timothy Tate, but it doesn't have to be this way

My heart is broken open. It began cracking at Sir Scott’s Oasis Restaurant in Manhattan, Montana. This supper club was the locale where it took a turn for the worse. No, it wasn’t due to the cholesterol marbled in my 12-ounce boneless ribeye steak; it was due to my sister and wife sitting across the family-styled table that did it.

I am a psychotherapist. I help others deal with mental pain and anguish. In this profession none of us are immune to the suffering that befalls our clients.

You see, my 86-year-old sister, Beth, mentioned in my recent column about the Miles City Bucking Horse Sale and Rodeo, was in town for her granddaughter's graduation from Belgrade High School. Susan, my wife, and I thought the casual easy-going yet well-oiled manner of this iconic steakhouse would fit her Miles City sensibilities. Make her feel at home.

We were right. She felt at ease and her straight up double Crown whisky smoothed out any remaining wrinkles. My sister, brother and I are not afraid of a stiff drink although we probably should be. Since I was driving, I settled for a 14-ounce IPA. Susan sipped on a glass of Pinot Grigio.

The first sign of my emotional cardiopathy was when the waiter asked for our order and knowing of my sister’s preference, I jumped into the crackling confusion about whether she wanted her drink with ice.

“No,” I said, speaking for her protectively. “No ice. She wants a double Crown straight-up.”

Beth is no longer connected to the pace, frequency and cadence of social exchanges. Her weathered face, strong chin, and thin, dyed hair looked like a motif off a Greek urn. The majesty of her life is torn into pieces and sprinkled around her language like flower petals peacefully drifting down the stream unaware of the approaching rapids.

There is a dignity to an old woman who not only doesn’t feel old but holds her place in the demands of modernity like a grandmother’s resolute station, seated on a bench next to bustling traffic, holding her granddaughter in her lap while stroking her hair and cooing a melody over her bowed head.

All of us wonder: how did we arrive near the last stop; where did the time go?

Hundreds of millions of older women are holding this space right now in their senescence. Beth was simply sitting across from me telling me the same story I’ve heard a hundred times again but this is who I saw since she had held me as her baby brother 70 years ago.

In previous columns I have explored the challenges of a daughter attending to her mother’s dementia and dying process. There are diagnostic terms that we can pitch at our elders but for now let’s stay with a more sanguine description, simply that my elder sister is drifting away fully aware of her condition but unaware of its complications and effects on others.

How do you let go of something or someone you can’t hold on to forever?

This is what I’ve been musing upon as I sit in the office where my clinical practice in Bozeman is located. I needed to let what I am writing about here first sink in. I could hear the words of the ”Happy Birthday” song bouncing over the Hawthorne playground and remembering that today was the last full day of school for the elementary school kiddos.

I decided to walk over to the playground and have the patina of another school year brought to a close, which I have watched and heard for years, into that place where it registers in the heart; this important rite of passage that will be recalled by those going through it 70 years in the future. Will they recall it with clarity?

I noticed that a large group of kids, parents and grandparents clustered around a woman performing a graduation ceremony for Hawthorne’s fifth graders. I ventured closer only to see at that moment the release of a dozen doves.

That’s the thing about commencement; it marks both an end and beginning.

Unlatching the schoolyard gate I ambled among the kids and parents before coming upon a young mother who has ventured behind The Blue Door and who gave me a strong hug saying, “This is the end of our family’s ten-year relationship with Hawthorne.”

Her bird had flown. Then I noticed that Lorca Smetana, a local farmer, healer, and ritual leader specializing in human resiliency, was responsible for the ceremony. There’s no one better. I went to give her a hug but she was engaged with a grandmother so I stood there quietly hearing another woman call out my name.

I turned towards her voice and heard her say in astonishment, “What are youdoing here!?” She too had been through The Blue Door during her pregnancy of the boy who was now graduating. I had also officiated at her wedding. We hugged and wept as if the miracle of this unexpected reunion was meant to be.

Such are the passages that if we reflect on them can become platforms for making meaning and that, when strung together across the years, can bring depth to the meaning of life. They become the cohesion and coherence rather than a collection of scattered parts.

The miracle here is that life’s wave train sweeps all of us along with its momentum regardless of what we think we know about the ride. Often, we focus only on what we might see at the destination without taking stock of everything else along the journey.

My sister asks me this each time we meet, “What is your first memory of me?”

More than a search for validation, it is about a longing to feel seen and when we feel seen it gives us a sense of having mattered. Reflect for a second on that joyous feeling you get when an acquaintance or someone else remembers your name.

It feels like we need to be remembered to know that our life carried purpose, that we affected others. This affect, the sensation that we are linked, crosses gender, generational, and racial barriers.

The haunting look in my sister’s eyes reflects the longing to matter, to mean something to someone. She seems to be asking, through the silence of her stare and the stories she tells, whether her life was worth living?

The sanctity of life is uncovered when we accept things as they are and not dwell on what’s missing or what we don’t have.

This is not a submissive act; rather it is an active engagement with how things are rather than the exhausting mental exercise of controlling others and outcomes in an overbearing and futile act to have life conform to our emotional needs.

The reconciled emotional state as seen in my sister’s visage is a hard won acceptance tinged with melancholy but wholly free of regret. Part of us involves being willing to give ourselves a break, to dwell in the richness of what we have and who we are instead of pursuing that endlessly insufficient prize of capitalism known as more.

Therapists too are vulnerable. My broken open heart is undefended.

I have heard it said that accepting personal vulnerability is a profound form of strength. Should we be able to calibrate the energy required to stay emotionally, spiritually, and mentally defended—the walls we put up for self-protection— we might find that that amount of energy is exactly what is needed for personal transformation. Each of us has the potential for transformation in us.

But like acceptance, neither is vulnerability an invitation to abuse. If we are not careful, life within ourselves and our interpersonal relationships becomes like the tennis match of blame/criticism volleyed over the net of agreements to be returned with a shot of enraged defensiveness: an exhausting match, producing no winners.

Aging has a way of either tempering or defeating us. Is it that way by design?

The tempering option means that we accept our inevitable common fate, that life is a terminal condition.

The fear that aging leads to the paradoxical defeat of death is a chronic condition exercising control of our world view from below the surface of our ordinary days. This idea brings me back to my sister stretched out in her lazy boy recliner in the master bedroom where for 58 years she has taken a nap to the flutter of song birds feeding at the feeder hung before the picture window she faces.

It is cruel and maybe the root of our malaise that we as a society do not hold our elders in high esteem and provide quality care and support for their elderhood as a national emblem of a dignified culture.

Should we need to struggle to patch together services from limping-along underfunded social agencies, begging for care that regular families cannot afford? Our society has turned old age into a trauma.

If we are the most powerful nation in the world but refuse to make care of the elderly and poor our priority then our might is simply defined by dominant empire values: conquest, nationalism, military might, and policies that protect the power elite.

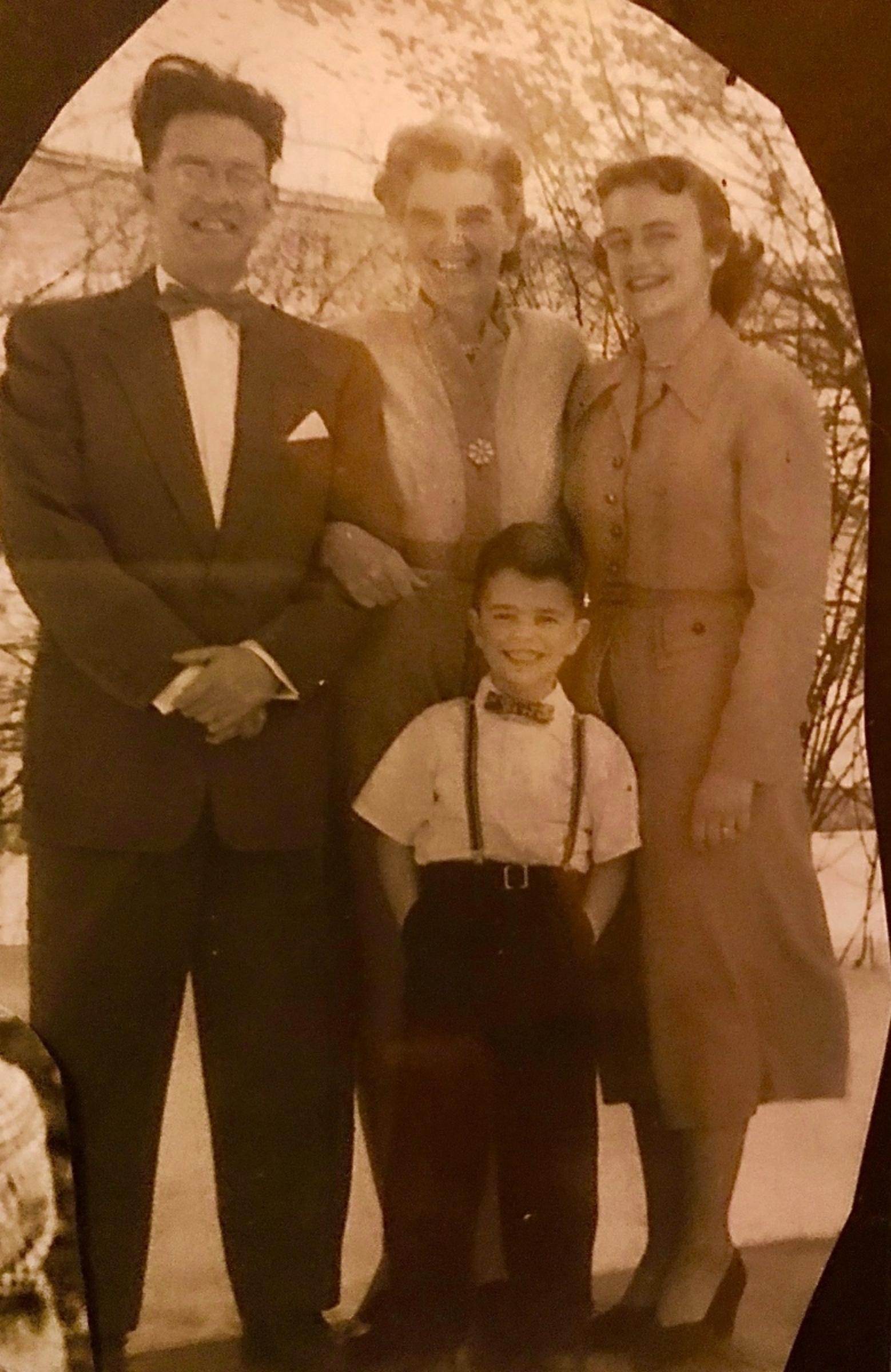

Sometimes when I look into my sister’s weathered steadfast face I see reflected the fate of everyone. That’s what busts my heart open. Once, she was a little girl, my big sister, may parents’ daughter and the wonder of that is still present. We were together when it didn’t matter what we would become.

Beth’s face is a mirror for our human condition: a sweet and sour mix of helplessness and strength, of hope tinged with certainty, of love defined by experience but no longer able to remember context or circumstance. Her only comfort comes in that moment of total lucidity when you don’t have to wonder if you mattered.

No matter how wealthy, famous, or defended, we each come home to our end with no guarantee of afterlife, regardless of how strong one’s personal beliefs may be.

One of the features of my private practice is that I like to have clients’ reading materials apropos their stage in life’s journey.

Recently I assigned the task of reading Viktor Frankl’s stirring account of his time in a concentration camp during WWII, the classic called Man’s Search for Meaning.

Faced with the most desperate and cruel conditions imaginable his words tell us of how finding meaning in life independent of circumstances is the gateway to liberation. This existential perspective dispenses with personal excuse no matter how justified a person believes they are.

Weeks ago, when I visited my sister in Miles City and shared my story in the last column, I walked down the carpeted hallway off her ranch house style home that was the nest for four children along with dozens of “adopted” kids who needed shelter.

Her 60-plus year marriage to Doc Winter Jr. provided the stability and means to provide for the less fortunate as well as a solid faith based platform for their children’s upbringing. Sure, there was trouble, conflict, gender-based roles, and an unshakeable faith in the Almighty. We were both the kids of a minister.

But underneath all of life’s negotiated agreements was a civility, a gratitude for life that breathed ease into family life. All of this rural context was fortified by annual family backpacking trips into the Beartooths, Absarokas, and Crazy mountains where I cut my teeth in the high country as a lad of 13.

Suffice it to say that Beth accepted no excuses for how challenging the last mile up to Pine Creek Lake or other treacherous switchbacks up to camp.

These memories flooded my head as I walked down the same hallway I ran down as a teenager. I came to the open door of her bedroom and peeked in to see her stretched out in her Lazyboy with a blanket over her, sound asleep.

Tears welled up in my eyes, not for her alone but for the warm-blooded care and striving of us soulful humans doing our best to live fully, lovingly, and graciously. I trust in her soft quiet slumber, if there is a dream about a big sister looking after her little brother, that she hears the whisper saying “you matter.”