Back to StoriesAmerican Shadowland: How Do We Stop The New Uncivil War?

Long ago, in Walt Kelly’s comic book series, his chief protagonist, a possum named Pogo, said to his critter companion as they negotiated their way through a swamp: “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

September 24, 2020

American Shadowland: How Do We Stop The New Uncivil War?As two Americas protest against each other, Timothy Tate in this op-ed says the only remedy is to confront the national shadow we've created. And it starts with each of us looking inward at ourselves

By Timothy Tate

“Character is like a tree and reputation like a shadow. The shadow is what we think of it; the tree is the real thing.” —Abraham Lincoln

Long ago, in Walt Kelly’s comic book series, his chief protagonist, a possum named Pogo, said to his critter companion as they negotiated their way through a swamp: “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

This simple psychological truth mirrors the encounter we The People of these fractured United States are experiencing. Part of this involves trying to reconcile the sheering forces of social conflict; another involves trying to find peace related to the conflict within ourselves during these covid times.

What does this collective trouble we are facing bode for the future? How are we to personally and collectively navigate these edgy emotionally-charged days? Are you feeling anxious, frightened, paralyzed, worried about what could happen between now and the election, and the events that may await us on Wednesday, November 4? You are not alone.

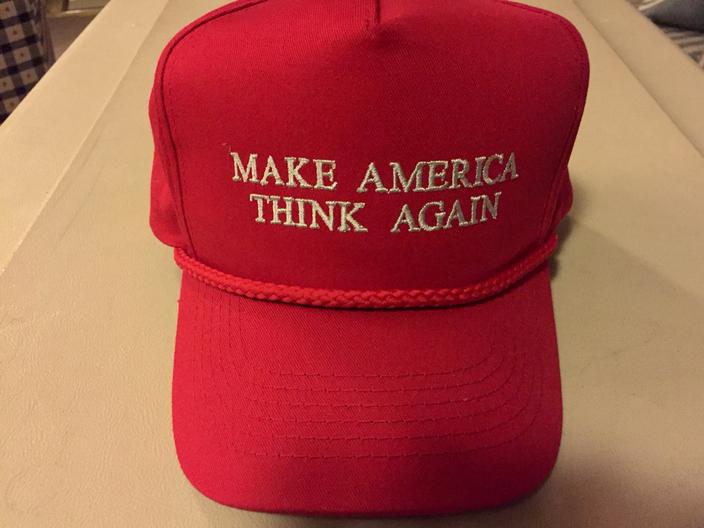

If we strip away the slogans and trumpeting, what is this enemy we are meeting?

I don’t know what the immediate remedy is for the angst, but I am concerned about the disjointed society we are becoming.

The other day I was leaving our local grocery store with fixings for the Labor Day weekend. It was the afternoon. I wheeled the grocery cart out of the store while cleaning its handle with Clorox wipes, waiting for a shiny fresh-off-the-lot Land Rover still holding its dealer plates, with all its symbolized privilege, to pass.

I next heard guttural diesel engine sounds before seeing two monster pickups waving flags and sporting political stickers turning into the market’s driveway. The vehicles went by each other, causing shoppers with carts to step aside for cover.

Did I expect them to stop for pedestrians? Well, yes. But I was surprised by my reaction to them blowing by on their way through the parking lot. The mud bogging trucks with mag wheels turned back onto Main Street where plumes of black smoke billowed from their stacks. They went charging through town making a circuit like teenagers do when they “drag” Main.

These motorists were politically dragging our once-quaint downtown thoroughfare, the road well-traveled and which represents the center of our community. They were making partisan statements intended to sow division.

I bowed my head.

The idyll of a true community is of a place to which we all want to belong, feeling interconnected and one would hope expressing compassion, empathy, relatedness and, need I say it, respect for someone in the crosswalk. At no other time in my seventy-plus years of life have I ever witnessed a national leader deliberately dividing and while plenty of colleagues in my profession have publicly assessed the pathology, that is not the point of this column.

Yes, many of you know, I am a practicing psychological therapist, and I am no stranger to direct eye contact nor opposed to using my middle finger when affronted by uncivilized behavior. I admit, the impulses for the latter are part of my “own stuff” that I have to deal with and own.

My bowed head felt more as I might behave at a funeral coping with sorrow. Unrelated to submission, my posture was a spontaneous expression of my psyche..

I could not bear to recognize nor identify those who drove the jarring mechanical beasts, behaving in a way that was obviously intended to provoke and, in a way, intimidate. Upon reflection, I take it to mean that such a brazen display reflected the enemy—not the dudes in the truck—but that which is within me. “Me” means the personal self as well as adding up via 330 million of we citizens to a collective “Us.”

What are we confronting if this sentiment is true—this wedge being driven deeper as if intended to split a circular whole piece of wood?

Family members who otherwise love each other can no longer talk about the events happening in this country because partisan inclinations—the President’s demand for loyalty—have taken priority over our deeper inter-connections that preceded him and ought to outlast him. Friendships have become shipwrecked. Covid has driven us into caves and the social tensions make many of us want to stay in them.

° ° ° °

Different therapists have different approaches. The model of psychotherapy that I practice in Bozeman, Montana is based on the assumption that there are invisible forces within the personal and collective Psyche that endure over time. Think of these as energetic patterns known as archetypes. A great way of imaging archetypes is to revisit the traits represented by Gods in Greek and Roman mythology as well as characters in every religious faith and their holy books.

One pervasive archetype affecting us all right now is the Darkside or Shadow of Life. The Christian belief system calls this, for simplistic reference, the Devil, as in “Devil get behind me,” or, more colloquially, “The Devil made me do it.”

Other religions and philosophies name and wrestle with this universal dark and enduring force such as Iblis in the Islamic tradition. This “evil” or satanic force appears to tempt people to stray from their righteous path—i.e. away from what they know in their conscience is the right thing to do.

As I’ve written before, I was raised a minister’s kid and from that I still deal with plenty of baggage that was imprinted on my own psyche early. What is confounding to many with rational minds is how believers of any established religion in this country can support leaders and personal conduct who, or which, parts company with what is supposed to reside as core ethical and moral principles.

My editor at Mountain Journal has told me not to delve too deep into religion and that MoJo examines issues and ideas and is equally skeptical of both major political parties. But he is allowing me to engage in a few musings related to our national psyche.

Would Jesus be a figure touting the US Constitution, promoting free market economics, and carrying a semi- automatic weapon slung over his shoulder welcoming the End Times, or would he be an advocate for the sick, poor, disenfranchised and dispossessed, unashamed to call himself a socialist? I'm reflecting now on what the image of Jesus was as I sat in the pulpit listening to my Dad's sermons in the 1950s.

If we as a so-called “Judeo-Christian Nation,” proclaiming slogans such as “In God We Trust,” are making excuses for people who defy or violate the moorings that are supposed to be guiding us, what does it say about us individually and as communities, states and the nation?

You might think of this duplicity, which could also be called hypocrisy, as a long shadow being cast. Our collective shadow, psychologically, is more than the sum of individuals confronting their own darknesses but is fed by the degree to which we as individuals shun personal responsibility for facing down what is right in front of us.

I suggest there are elements within our personal and collective Psyche that if brought to light might help us understand the symptomatology of: Black Lives Matter, Indigenous Rights, Antifa/Facism, risky Covid-19 behaviors, QAnon speak, Pro Choice vs. Pro Life, political rhetoric on the “Right” and the “Left,” and the throes of an adolescent democracy surging towards an election that will reinforce or transform our current cultural chaos. Mind you, I am not equating any of the above but they're representative of how Americans are sorting themselves.

Everything we do emanates from how our mind perceives the world. Your personal life experience is akin to a journey’s story line. Let’s say that you are the captain of your vessel, your body and mind, and your name tag reads: “Captain Ego.”

I’ll shy away from how the term “ego” came into play as a household word we use in our daily parlance. Ego is something that can be easily inflated and quickly deflated. Our ego prefers to be in control, seeking approval, disdaining the unknown. The illusion of control—and the thought that we are totally in control of our lives is an illusion— is based on a human need to feel like we know completely what is happening to and around us. For many, the prospect of “not feeling in control,” when dealing with daily life, unexpected events or survival, can be uncomfortable, if not unbearable. Hence, the urge to flee back into the cave.

The trouble with this approach to life is that the ego’s cornerstone is a shame-based composite, more like flaky sandstone than solid granite. In simple terms, this dark composite’s main element is the belief that by our very nature we are inadequate, flawed, scourged by original sin, unworthy. It might register as a feeling that we are unworthy of respect. The most penetrating manifestations are of feeling that we are unworthy of being loved or unworthy of even being seen by others. Egoist expressing often emerges as a contervailing coping mechanism for dealing with feelings of inadequacy.

Another compounding element that factors into ego is guilt—we all have some, you know, the feeling of thinking you've done something wrong? A sibling of guilt is shame. The difference between the two is that shame cannot be atoned whereas guilt can be, as in: “Have you no shame, Senator McCarthy?” or “do you not feel badly about what you did?"

Shame is a condition and guilt an act. Shame is, in one way, a culturally-reinforced moral compass whereas guilt is the sense of conscience. In practical terms, think of it this way: A judge will ask the alleged criminal if he or she feels badly about what they did, not who they are. What they did is often a symptomatic expression of who they are, or who they thought they had to be.

Similarly, people who are judged guilty may think to themselves, “I didn’t mean to get caught” rather than “I am such a miserable soul” or “I want to be held responsible for my actions and discover why I did what I did.” Of those three responses, can you guess which leads in the direction of better mental health and addressing one’s shadow?

People who are judged guilty may think to themselves, "I didn’t mean to get caught” rather than “I am such a miserable soul” or “I want to be held responsible for my actions and discover why I did what I did.” Of those three responses, can you guess which leads in the direction of better mental health and addressing one’s shadow?

It isn’t as simple as asserting that an individual—or a country— is suffering from moral bankruptcy or a lack of conscience. Yet the distinctions serve as a way for thinking about shadow, as a way of understanding the forces behind shame beliefs and guilty behaviors.

Sigmund Freud suggests that these are instinctual forces rooted in the human psyche (the soul, mind and spirit) and driven by primal instincts. There are those among us who protest injustice and are motivated by what Dr. Freud called the Superego—our learned sense of what is right or wrong.

This superego is in chronic tension with our primal drives, what is called our Id. The conflict zone of these two opposing forces is our ego. The libido, another term in the lexicon, is the energetic drive that manifests the conflict in sundry ways. If I am unaware or unwilling to tackle my shadow I will act it out according to my personal Superego-Ego-Id complex’s competing demands. Sorting out motivations for our behavior is enriching and meaningful but it is damned tough and requires introspection which is why so few people actually do it.

Why? Because doing do often means we need to challenge entrenched belief systems and modify them. Why is it so hard for our white society to acknowledge and answer to charges of white privilege, having a culture of white supremacy and institutionalized racism? This is why. It is frightening to have our imperfections brought out of the shadow and into the light.

A person who is unconscious in relationship to self-knowledge will act out their fear aggressively whereas an individual who is striving to take responsibility for their shadow will introspect on how fear is causing them to have contempt for others, or to blame people for their ways, or to project their own flaws onto others, or to withdraw, or to bellow in frustrated rage.

Yes, and don’t presume otherwise, but these conflicts exist for people who identify as Liberals and Democrats as much as Conservatives and Republicans.

A person who is unconscious in relationship to self-knowledge will act out their fear aggressively whereas an individual who is striving to take responsibility for their shadow will introspect on how fear is causing them to have contempt for others, or to blame people for their ways, or to project their own flaws onto others, or to withdraw, or to bellow in frustrated rage. Yes, and don’t presume otherwise, but these conflicts exist for people who identify as Liberals and Democrats as much as Conservatives and Republicans.

At times when we are confronted with the scope of troubles, the odds are that we will emotionally withdraw as if thinking or feeling, “I can’t deal with it; it’s just too much.”

Someone locked into a contracted state may appear as a rifle-toting person protecting ill-conceived notions of liberty. Or, it can take the form of a contrite protestor, feeling self-important and righteous, who feels helpless to effect racial or social inequity and feels shame about slavery, the ethnic cleansing that occurred with indigenous people and chronic undeniable issues of social inequality.

Neither the self-styled “patriot” nor the protestor can return to some fantasized “better time” nor change the history of white masculine privilege in America that enslaved, robbed people of land, massacred and committed genocide. What happened in the past is neither your creation nor your fault.

Individuals can no more alter what came before them than take responsibility for individual acts carried out by their ancestors, but individuals can—and should— acknowledge the privileged advantages and inherent biases that have been handed to them and then decide which steps they will take going forward to account for them. Of course, some aren't interested in doing that, especially if it means it will cost you something.

If one is well off today based upon being heired a fortune accrued from slave labor, it can be argued that in that case, a discussion involving some kind of reparations are in order. But what does that look like? In the case of settler and colonizer descendants who are living today on lands taken illegally from indigenous people, an argument can be made that all of us who hold deeds to such land have a responsibility to redress injustice. But what form will it take?

It might make us feel better—assuage any guilt or shame we might have for living more comfortable lives than those who struggle and have less—but just talking about unjust acts if you are a white person, cathartically making empathetic statements on Facebook or righteously walking in a march alongside People of Color does not by itself remedy the problem. Even those who awake to the advantages of their own privilege often struggle to come to terms with it—when it’s all they’ve ever known.

So, back to Bozeman, Montana. What motivates the driver of a pick-up truck revving the engine and driving down Main Street claiming to be a patriot with a flag waving in diesel smoke? What motivates a white person in marching down Main Street in protest of the status quo that has harmed People of Color? Books already have and will be written about why.

We are in the very early innings of pondering an America that really does reflect the language in the Constitution. Healing in this country is going to happen not by judging people who have differing political views, no matter how offensive one side sees the other, but in trying sincerely, as difficult as it is, to understand them. Sitting down and listening. Getting to know them. Trying to relate to them as human beings. Those in power pondering how life is when perspective is turned 180 degrees.

I’ve seen transformation happen when an admitted white racist dad had the courage to sit down with a black man and listen to him explain how he and his wife worry the worst might happen to their teenage sons every time they get into a car and drive away.

Fear of change that incites behavior in one person is hard to reconcile with that of another who believes justice delayed is justice denied and change cannot happen fast enough. Being told that one ought to be ashamed, guilty and self-loathing based upon sins committed in the past or because of the color of one's skin is difficult to reconcile with the passions of a person who believes that shaming and guilting others into submission or silence is an effective tool for achieving change or compelling another to listen and have empathy.

Our identity culture reflects this times but it is fraught with land mines and one could argue that it actually hobbles the cause of diversity. Each of us is more than our race, gender, sexual orientation and political leaning and those can evolve or change over time.

If the rationale for protests and counter protests is demonstrating for a cause, then logically we ought to ask: What are the measures of success and how can we together derive deeper meaning personally and collectively?

Sowing more division as a response to division without consideration given to how it can lead to more empathy and compassion for each other and, of course, yielding justice, equity, diversity and inclusion will not produce a better country. As our history has demonstrated, change must sometimes happen through coercion. In situations where power, unjustly wielded and held, refuses to yield, civil disobedience to force change may be the only option when those who claim to possess rights want to prevent others from having them.

This stuff is messy. Meeting violence with violence, as in arguing that communities need to defund police while, at the same time that law enforcement is needed to stop bloodshed and looting does not engender empathy from those most resistant to change and most in need of heeding change's necessity.

Again, giving serious consideration to why we do things can, if we allow ourselves to be vulnerable and understand the motivations can become a valuable and potent form of soul searching. And it is probably the only way we can confront the shadow.

Let's not kid ourselves: We are in a seriously perilous, precarious place with the convergence of political divisions, a plague and a depression happening all at once. There comes a point at which the unthinkable becomes unstoppable and then must run its course like a wildfire.

For the first time in the history of this country, we have a leader who will not commit to a peaceful transfer of power. In his mind he has already won the election; there is no need to hold one; he has invalidated the write-in ballot process, saying it is corrupt without evidence, and members of Congress in his own party, including politicians from our states, are not challenging him in his refusal to adhere to the long-established rule of law. Call it what you want, but that isn't democracy.

Many believe that we are fighting for the soul of the United States. If that is true, then it ought to be our patriotic duty to face the shadow of our society together before it is too late.

The only lasting method of reconciliation that I know of is to face the black hole of our inherited shame and to make amends for the personal transgressions of which we all are guilty. Healing and meaning happens first on the inside, not in chanting a slogan of power at a political rally or in a street march but by being willing to make real change in your life.

This I know from having interaction with hundreds of clients: Inner peace never lasts without forgiveness and, at a societal level, as Archbishop Desmond Tutu says, referencing the truth and reconciliation hearings that happened in South Africa after centuries of Apartheid, a society must first speak the three hardest words for a human to utter: "I am sorry." It is the first step in taking responsibility for harm done to others Such a psychological encounter, however, is not for the faint of heart.

We as humans are hard-wired to avoid accountability. It is easier to tout the virtues of religious beliefs or cast oneself as a patriot rather than conducting oneself in a way that emanates empathy, kindness and love as Christ taught, or in understanding what Abraham Lincoln meant when he said, condemning slavery, that “a house divided against itself cannot stand.”

Even during the Civil War, amid the bloodshed of competing social and economic ideologies, Lincoln did not try to malign the political party of his rival in the race for the presidency as being disloyal or trying to destroy America. In the 719 words of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation he implored privileged Americans—white Americans—to heed the calling of their better spiritual and civic angels by pulling together. And we should not forget that thousands of American white males on the Union side gave their lives so that slavery could be ended.

The paradox of the trouble we’re in now is this: we need a unifier who will put country before his own self. However, if we think that we must have a great emancipator in the Oval Office to Make America Great or conversely, deliver us out of these dark times, we are delusional. We cannot turn to others to save ourselves and it is only by a collective personal reckoning that the symptoms of an infirmed society can be healed. Yes, there is truth to the expression that we must be the change we want to see in society.

Is adherence to a political party more important than striving to be a better person, a better citizen, a better believer who embraces the most virtuous expressions of faith? If the answer is the former and not the latter, we will be moving deeper into a darker shadow where there is danger for us as individuals and collectively for our country. Yes, voting is the most potent way that our individual life and our civic life converges. But it’s what we do before and after we step into the booth or mail in our ballot that matters more.

Individually, we need to ponder—and take responsibility for— what kind of people we want to be because that is the only way to escape the shadow of our moral and ethical contradictions. Doing it together is how it ripples at a societal level.

We know in our hearts and rational minds what to do. Pogo and Honest Abe are there to remind us why.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Original artworks in oil by John Felsing. Check out more of his work by clicking here. Used with his permission. What do you think about Timothy Tate's op-ed? Drop us a note if you have comments you're willing to share. Keep them civil and no longer than 300 words.