Back to StoriesGame Farms Should Warrant Greater Scrutiny In Age Of Disease Pandemics

April 21, 2020

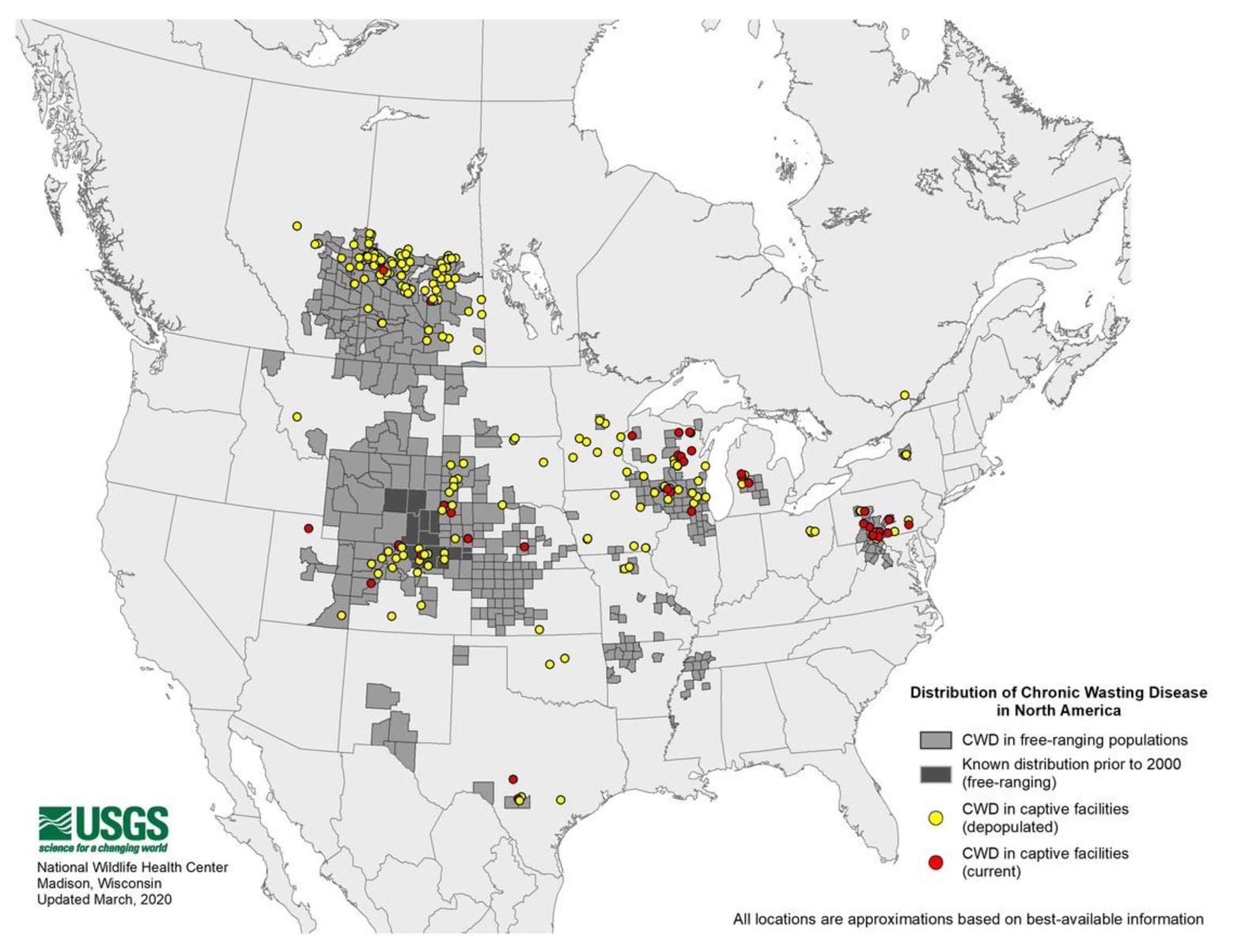

Game Farms Should Warrant Greater Scrutiny In Age Of Disease PandemicsIn this op-ed, Wayne Pacelle calls out a controversial industry, profiting off of captive wildlife, that has been linked to spread of Chronic Wasting Disease

By Wayne Pacelle

Private game farms keep deer and elk behind big fences, slaughter them for meat or velvet, and invite fee-paying hunters to shoot some of the quarry in a guaranteed-kill arrangement. Called "canned hunts," It’s about as sporting as shooting an animal in a zoo pen.

But this startlingly large industry—with perhaps 4,000 enterprises in the United States, according to the North American Deer Farmers Association—has been been linked to the spread of Chronic Wasting Disease throughout the United States.

CWD is a brain-destroying disorder like Mad Cow Disease that turns the brains of deer, elk, and moose into Swiss cheese. It’s a threat to the captive deer and the wild ones. And maybe someday, experts says, to the people who consume the meat after the hunt is complete.

Wondering which animal industry is poised to spawn the next animal or human health epidemic like Covid-19? Well, here’s one candidate for the list of plagues in progress.

Perhaps the least noticed of the major animal exploitation industries in the United States, game farms quietly operate in more than half the states, with 60 percent of them in Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Texas.

Montana citizens went to the polls in 2000 and passed a referendum banning new game farms from being created in the state. Wyoming did the same in 1975. They are legal in Idaho. Earlier in 2020, Montana got a reminder of the connection between game farms and CWD when the disease was confirmed in elk at a game farm in the eastern part of the state.

At some game farms, deer and elk are bred to produce antlers so big and heavy that some animals can’t raise their heads. These commercial wildlife-killing enterprises have been part of the equation of CWD spreading to wild deer in many states

At game farms large numbers of animals are often bunched up. It’s thought that nose-to-nose interactions between captive and wild deer through fencing or captive animals escaping from farms are the most common forms of CWD transmission to free-roaming animals.

But there is no live test for the disease and symptoms may not manifest for years, if ever. Trucking deer for sale between farms can allow the disease to spread overnight to areas previously without infections.

Not even hunters who are microbiologists can determine if the animals they slay in the wild and then serve up to their families have been infected with prions, the nearly indestructible agents of the disease. In fact, infected deer, less alert and fleet than their prion-free herd mates, may be more vulnerable to hunters, potentially increasing human exposure to CWD-tainted meat. Like Mad Cow Disease, CWD could, potentially, someday infect people with its human variant Creutzfeld-Jakob Disease, causing dementia and a fatal brain disorder.

The abnormal proteins that cause CWD to survive in the soil for long periods of time also enable the disease to remain in the environment for years.

Minnesota is the latest state with a significant surge in CWD cases. The Minneapolis Star Tribune reports that after learning of a disease outbreak at a deer farm, the US Department of Agriculture pays farmers to “depopulate” their herds, slaughtering all of the animals.

In the past three years the USDA has doled out over a half million dollars to deer farmers in Minnesota and Wisconsin, just as the federal agency has paid millions to cockfighters in California to kill their birds after two major avian influenza outbreaks there. Yes, you’ve read that right: the USDA has been compensating cockfighters and deer farmers for the disease-transmission problems they’ve been primarily responsible for incubating and spreading.

With state fish, wildlife and agriculture departments pointing to an abundance of deer eating crops, consuming ornamental shrubbery, spreading Lyme Disease, and being hit by cars by the tens of thousands on highways, one might ask why still more deer are being bred and then crowded in densities creating conditions ripe for the emergence of CWD.

CWD was first discovered at a government research facility in Colorado in the 1960s. Since then, it escaped into the wild and has spread to 25 states. Since the disease was detected in 2002 in Wisconsin— which has had thousands of confirmed cases—the state, as of a few years ago, had spent more than $45 million to contain its spread. But the state is apparently spending little now on the problem even as the outbreak gathers momentum. The order to shelter in place, apparently, has not been heeded by the deer, and the zombies are on the march.

Some conservation-minded sportsmen grasp the idea that the best way to stop the disease is to shutter the game farm. Even the Montana-based Boone and Crockett Club, an organization founded by Theodore Roosevelt, oppose the slaying of fenced, diseased animals with giant racks to preserve the sport itself from self-ruin.

Yet still, too few voices within the hunting community are sounding the alarm about the threat. Even prior to the detection of CWD in Montana’s wild deer population, Montana voters passed a ballot initiative banning captive hunts and halting the establishment of game farms.

Other states have not been as foresighted and, despite CWD outbreaks, have not taken meaningful steps to phase out deer farms or to alert hunters to the impending health threats from eating infected animals. The two biggest hunting states, Pennsylvania and Texas, each have more than 1,000 deer farms, according to the industry trade group.

Deer farmers tout the revenues generated from the meat, hunts, and “velvet” from the antlers of the animals they breed, confine, and offer up for killing. But how can policy makers endorse this practice from an economic or wildlife management angle if the government must spend tens of millions of dollars to contain CWD—if CWD has the potential to devastate deer herds and cause a sharp decline in hunting license sales, and expose hunting families to the consumption of meat that might bring them dementia?

Here’s an area where true sportsmen and animal advocates have a shared purpose. By bringing a halt to deer farms, we have the potential to end the crass commercialization of wildlife and prevent the spread of a nearly indestructible prion that can kill animals and maybe people. With the nation having tens of millions of wild deer and elk, what kind of lunacy is it to swell captive populations even more for these nefarious purposes?