Back to StoriesIs 'The Gallatin Way' Being Lost?

January 27, 2022

Is 'The Gallatin Way' Being Lost?A historic scenic passageway to Yellowstone, the Gallatin Canyon is today undergoing profound change. Duncan Patten in his sweet book reminds us what's still at stake

by Todd Wilkinson

In a region known for its scenic drives through the mountains, this one, too, ought to rank right up there, wending literally along the banks of a famous blue-ribbon trout stream, connecting the fastest-growing micropolitan area in America to a quainter western entrance to Yellowstone National Park.

Two-lane US Highway 191 is a marvel of engineering that continues to be upgraded and yet, paradoxically, the more conducive it becomes to carrying higher loads of traffic, the poorer it bodes for the wild sense of nature through which it circuits.

Nothing transforms wild places more, the eminent conservation biologist Reed Noss has said, than a road being built into previously little-developed landscapes. Indeed, the bulging presence of Big Sky, which is steadily displacing one of the last great concentrations of large mammals in the Lower 48, would not exist were it not for US Highway 191.

Ranked among the most dangerous roads in Montana, with white cross markers adorning its asphalt fringe, and every year notching grim statistics related to road-killed elk, deer, bighorn sheep, bears and even wandering pets, US Highway 191 has a notorious reputation, especially during icy winters.

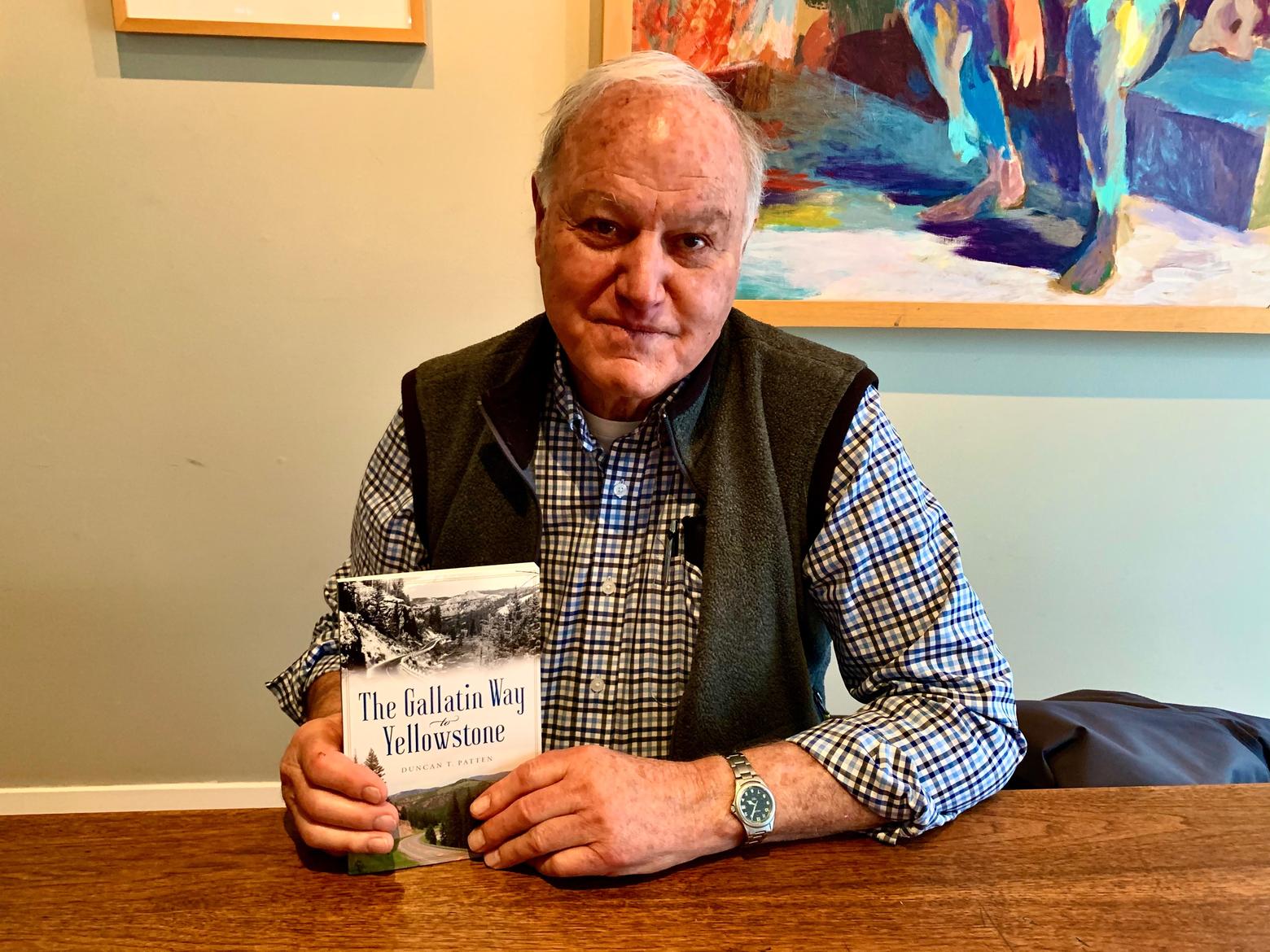

And yet this stretch, which brazen semi drivers use as a shortcut for hauling freight, also has a storied history—one that is recounted in brilliant and inspiring detail by Gallatin Canyon resident Duncan T. Patten. Patten’s book, “The Gallatin Way to Yellowstone” has been sitting on my desk for a while, becoming dog-eared and marked up with highlighted passages from its illustrated pages.

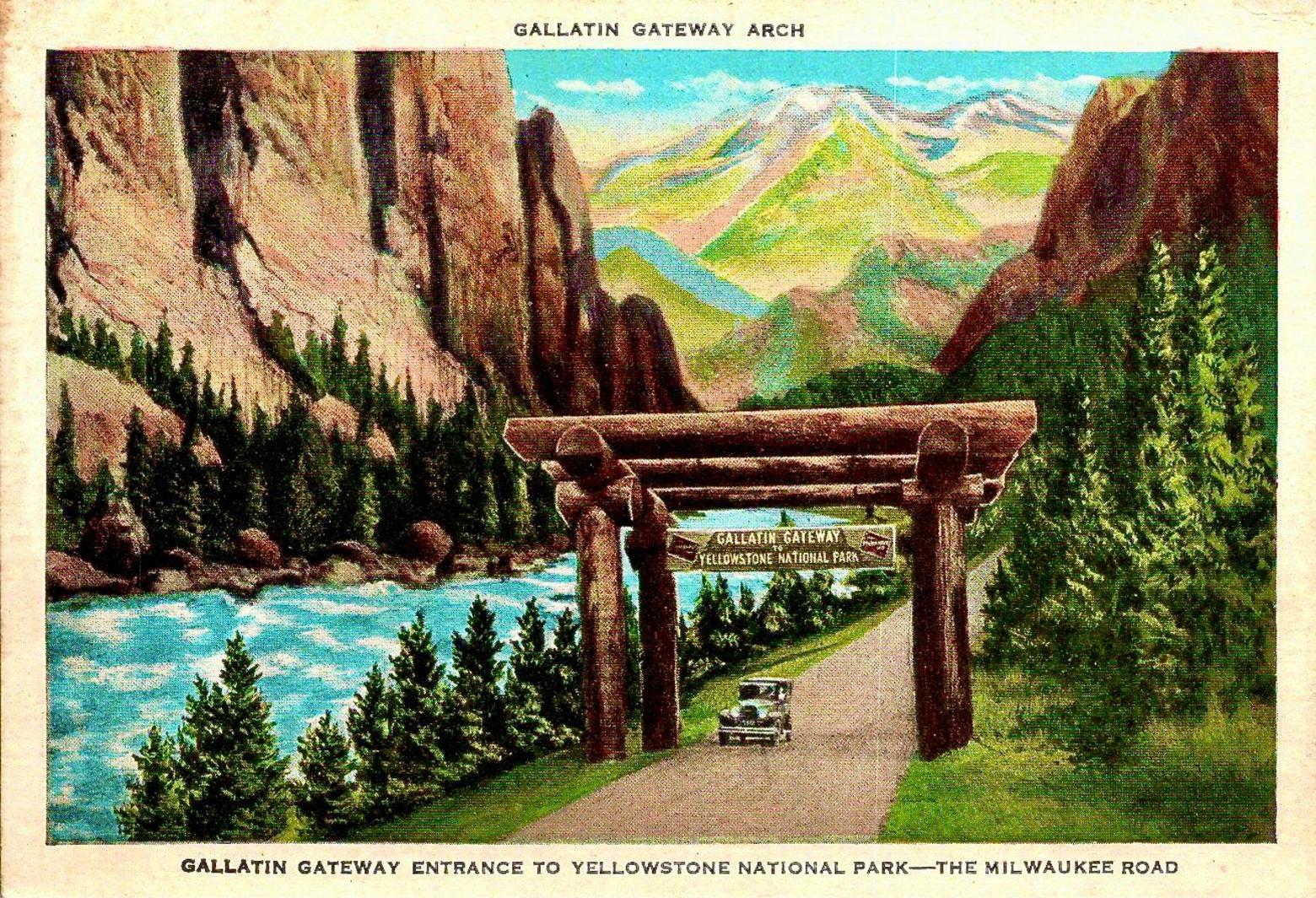

Long before US Highway 191 became the hair-raising experience it can be, parts of it were old trails for indigenous people moving to and from the mountains we know today as the Gallatins and the interior of what became Yellowstone. Subsequently, after Yellowstone was founded 150 years ago in 1872, a nascent road was given the poetic-sounding moniker, “The Gallatin Way” and it became the focus of continuous re-tinkering.

First it was turned into a muddy pathway for stagecoaches, advocated by the Bozeman Chamber of Commerce, to give tourists a shortcut to the back west door of the world’s first national park and its geyser fields. Then it gave access for dude ranches, livestock growers, prospectors and timber companies. Over time, it became an economic lifeline and then, following the birth of Big Sky, it became a road underbuilt for the high volume of traffic it holds now—levels that rival the kind of bumper to bumper commuter traffic you find in any urban suburb.

Unfortunately, state and federal highway engineers who dream of continually straightening, widening and expanding the footprint of US Highway 191 also stand accused of being callous, or, at best, indifferent, to the accruing negative impacts of their work. You know there’s a problem when the aesthetic impacts of a road flanking a river not only diminishes the once-quiet ambiance of the flowing water beside it but is treated as a more valuable commodity.

Every glorious river valley in Greater Yellowstone and indeed the Rockies with a highway astride of rivers is dealing with the kind of transformative issues that are only accelerating in the Gallatin Canyon, leaving one to ask: Is all progress good? Is there any kind that can happen without destroying the spirt of place? Can any of it be prevented?

One passage struck me in the early pages of Patten’s book. “Long-term residents of the canyon and locations farther south often viewed Big Sky as a blemish on the beauty of the canyon, while others now see it as an integral part of today’s canyon and the Gallatin Way,” Patten writes. “Change is normal—everything changes over time; thus, how the canyon and the Gallatin Way have changed is a lesson to recognize that we ‘cannot burn back the clock.’”

Lest anyone mistake Patten’s intention, he is neither a booster for the kind of development that is continuing to erupt largely unchecked in the Gallatin Canyon nor is he condoning the thoughtless forms of real estate speculation and monetization of nature that continue to exact a toll. He is imploring all of us to pay attention, to appreciate the canyon not as a Colorado-like thoroughfare leading to a major four-season resort, but to heed that this road actually passes through the northwestern corner of Yellowstone National Park.

Let’s underscore the significance of that fact. Yellowstone and the Gallatin Range that rises above the east side of US 191 hold all of the major mammals that were on the landscape prior to the arrival of Europeans on the continent. Grizzlies. Wolves. Bison. Moose. Wolverines. Bighorn sheep. Mountain lions. Elk, to name a few. (Plus, there’s the glittering jewel of the Gallatin River, which already has been tarnished by sewage problems related to development around Big Sky and, on a few occasions, algae blooms).

Patten wants travelers to take stock of this as they motor through—hopefully prompting them to slow down, make less haste, being more attentive and knowledgeable, soaking in that amazing fact of wildness as expressed by bio-diversity. First coming to Gallatin Canyon as a boy to have a dude ranch experience in 1943, Patten is revered as "the old guy in the canyon with an unwaveringly astute memory."

"Part of the fun and challenge of using repeat photography is trying to find locations where original photographers stood. In some cases those locations have disappeared, because of highway routing or other things," he told me, noting that engineers in some places actually moved the river out of its original bed.

Patten is not only a fine writer; he’s an astute ecological thinker, counted among the best in the West. Wielding a specialty in hydro-ecology, he is known for examining how river ecosystems—the most biologically rich parts of landscapes—function. During his career, he’s been involved with a number of different studies on Greater Yellowstone issues undertaken by the prestigious National Academies of Sciences.

Most of all, Patten, his wife, Eva and their family have been denizens of the Gallatin Canyon for generations, owning a historic ranch themselves and their care for the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem has turned them into avid conservationists.

It’s fair to say that probably the majority of people, who cumulatively log millions of miles passing through the Gallatin Canyon every year, are unfamiliar with the history of how the road beneath their tires came to be. Patten’s book and its trove of imagery provides a fascinating remedy for their lack of awareness and ought to be required reading for all public land managers, realtors, developers, and anyone headed to ski, hike, hunt, fish, ride mountain bike or horseback, or even race between Bozeman and West Yellowstone.

“The Gallatin Way to Yellowstone," which invites us to ponder how we can secure more respectful treatment of nature by pondering the past, should be on every bookshelf. Let it not become a painful reminder of something irreplaceable that we let slip through our hands.