Back to StoriesGiving Grizzlies Their Legal Voice

July 19, 2020

Giving Grizzlies Their Legal VoiceRobert Aland, a tax attorney from Chicago, credits bears with turning him into a citizen advocate for nature—as he believes all residents, even part-timers, should be

There are, arguably, many different kinds of part-time Greater Yellowstoneans who either own vacation homes here or visit often in order to relax and play.

There are those who simply want to escape to a wild West version of Disneyland. They arrive to get away from somewhere else, having little interest in fraternizing with the locals, paying no heed to what’s going on in our region day to day and may view their time in the Northern Rockies as a one-way relationship—as in: “What can I experientially take from the ecosystem, to serve my own immediately desires, without being burdened by considering how I might possibly give back?”

There are others who may

interpret the region as being a province of quaint rural bumpkins. These

visitors may contribute to local community causes such as the arts, a hospital or food banks but they may have no understanding of how important conservation has been in protecting the things they savor. Many fail to grasp how Greater

Yellowstone is qualitatively different from any other landscape in the country.

And then there are those who

educate themselves, who proudly possess a level of ecological literacy in understanding

how Greater Yellowstone is, from a wildlife perspective, one of the most

remarkable bioregions left on the planet.

These people (politically they

may identify as left or right) get involved in conservation. They embrace

the ethos of being net givers rather than takers, and they don’t flinch if

identifying as tree huggers gets them criticized in certain circles.

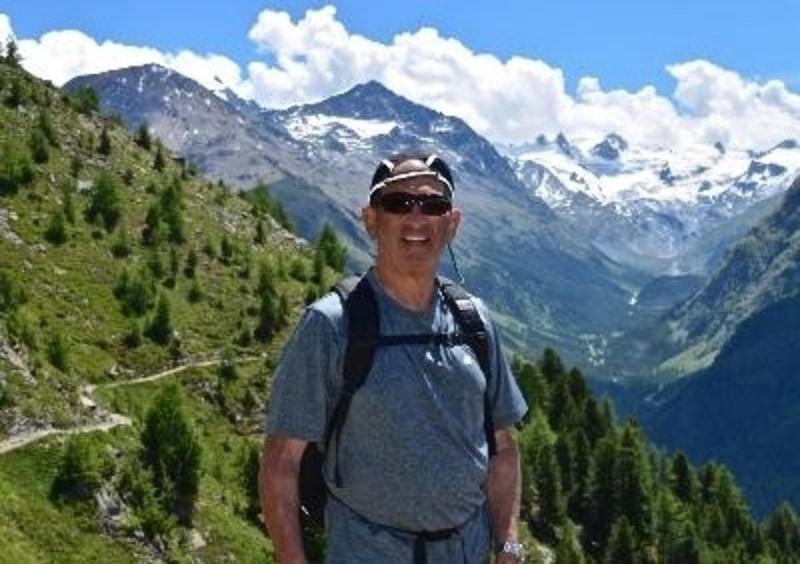

Robert Aland fits into the

latter. Aland is a veteran tax attorney from Chicago, who had a long practice

before he retired and he still reaches tax law as an adjunct professor at the

Northwestern University School of Law.

He knows the importance of

balancing ledgers and has a keen ability to recognize when numbers don’t add

up. Aland and his wife are passionately devoted to advancing the cause of

conservation for an animal that is the quintessential emblem of wildness in

Greater Yellowstone: the grizzly bear.

The Alands reside part-time in

Wilson, Wyoming and have been coming to Jackson Hole since the 1970s. Back then, grizzlies had been largely killed off in Teton County by hunters, ranchers, outfitters and poachers.

Recently, he as an individual plaintiff joined a wide range of conservation groups, indigenous tribes, elders and others in suing the US Fish and Wildlife Service. In particular, they emerged

victorious in a US district court ruling in Montana (a ruling upheld July 8 by

the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals) that overturned the Fish and Service’s

decision to remove Greater Yellowstone’s grizzly population from federal

protection.

Inciting national outrage, what

the Fish and Wildlife Service’s action did, in removing grizzlies from federal

protection under the Endangered Species Act, resulted in the states briefly

taking over bear management and, in the case of Wyoming, moving quickly to monetize

bears by selling licenses to shoot 23 of them.

I

asked Mr. Aland, who just turned 80, what prompted his involvement in the case

personally, volunteering his time as an attorney? “Since I was a small child, I have been disgusted

with the treatment of wildlife by humans. When my father took me to the

Ringling Brothers Circus in my home state of Alabama, and I saw lions and

tigers walking in circles in small cages or being tormented for public

enjoyment and elephants walking single file with trunks grasping tails, I asked

my father to take me home,” he said.

Aland added, “I believe trophy hunting is

particularly disgusting. It is not a sport. A true sport involves

two or more competitors, equally equipped, playing by the same rules—let the

best competitor win. Sneaking up on an unsuspecting animal with a

powerful weapon and killing it for fun, profit or personal validation is not a

sport. This brings me to grizzly bears in the Lower 48, which were nearly

exterminated by the time they were given protection in 1975 under the

Endangered Species Act.”

Aland, who says there's no retirement age in being a conservationist, sees himself as being a kind of “defense attorney for bears that cannot speak

for themselves.” He admires the non-profit law firm EarthJustice and its

staff in the Bozeman office led by senior litigator Tim Preso (who earlier in

his life was a journalist).

Two

summers ago, Aland and other plaintiffs prevailed

in convincing US District Court Judge Dana L. Christensen to halt Wyoming’s and

Idaho’s plans to stage their first sport hunts of grizzlies in 44 years.

Aland is incredulous that after decades of Americans rallying to save grizzlies in

Greater Yellowstone, increasing the number of bruins in the vast region from

around 140 to about 720, Wyoming wanted to offer nearly two dozen up for

hunters.

“The bottom line, consistent with my feeling about

wildlife since childhood, is that I want these bears to be protected and

preserved forever,” Aland said. “I want the number of bears in the Lower 48 to

increase steadily and naturally. I do not want the bears to become decorations

on family room floors and walls.”

Aland

understands how visitors to Greater Yellowstone and second home owners might

want to enjoy their time here without reflecting on what’s at stake from a

conservation standpoint for bears and public lands. But he disagrees with such

thinking. They ought to care, he says, because the wildlands of the

region belong to them too and as citizens they need to be advocates. When

Aland isn’t scrutinizing government documents, working with others to file Freedom of Information

Act requests and traveling to hearings, he spends part of his time in Wyoming volunteering

for the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation in helping landowners take down barbed

wire fences that are dangerous obstacles to safe wildlife passage.

Some

15 years ago, Aland admits he didn’t know much about the Endangered Species Act

and its purpose. He poured himself into studying the law and has volunteered,

by his rough estimate, about 7,000 hours of time to making sure the legal

framework for safeguarding bears and other imperiled species remains intact.

In

my communication with Aland, who is being careful and sequestering himself in

this time of Covid-19, I asked him if he thought the states and federal

government fully comprehend how beloved Greater Yellowstone’s population of

grizzlies is by the public and what those civil servants need to heed.

“Yes, there is no question that the federal and state

governments understand completely how beloved these bears are to the American

public. However, the governments arrogantly disregard public opinion due

to pressure from politicians, trophy hunters, ranchers and resource exploiters

that seek access to the bears’ ‘critical habitat,’” he claims. “Let me give you

objective proof.”

Aland notes that when Yellowstone-area bears were

first proposed for removal from Endangered Species Act protection in 2005,

members of the public submitted 200,000 comments, which was a large number.

According to statistics published contemporaneously

by the US Interior Department, over 99 percent of the comments, including 90

percent from residents of Montana, Wyoming and Idaho, opposed delisting.

Nonetheless, Aland says the Interior Department

disregarded the expression of overwhelming public sentiment by saying it didn’t

have to recognize it, as it wasn’t a formal referendum. Still, he believes that

wildlife management ought to reflect the desires of citizens.

Shortly thereafter, a court decision overturned the

government’s first bid at delisting but four years ago, the Fish and Wildlife

Service and the three states tried again.

“Fast forward to 2016, when the Interior Department

issued its second proposed delisting rule,” Aland says. “This time the

public filed about 665,000 comments, an even more astounding number. There is

no doubt that the public sentiment against delisting in 2016 was as

overwhelming as in 2005, but the Interior Department, under severe political

pressure to delist the bears, refused to publish the statistics as it had in

2005.”

Those 665,000 comments represent one of the largest

outpourings of citizen involvement on a wildlife issue in US history and he is

convinced the overwhelming majority was opposed to delisting and trophy

hunting.

When the Ninth Circuit Court ruled in early July of

this summer to uphold a lower court decision, that the Fish and Wildlife

Service’s justification for delisting was based upon flawed reasoning,

including failure to consider critical facts related to future survival of

bears, Aland says. He notes the courts correctly considered science and the legal

intent of law when it comes to “recovering” a species.

No other wildlife issues in modern times have

aroused more public interest than that of Greater Yellowstone grizzlies. Aland

believes the federal government has made a mockery of the public involvement

process because, on the one hand it solicits citizens, as mandated by law, to

become engaged in a significant wildlife conservation decision, and, on the

other hand, it dismisses what they have to say.

Aland may reside in Chicago but his heart is in

Greater Yellowstone. Grizzlies, he adds, are a national natural treasure “to be

conserved, not for the purpose of hunting them.” He knows not everyone agrees

with him, especially those who want to stalk a grizzly with the gun, but as a

person who pays close attention to numbers, he insists most do.

Where public support for conservation is concerned

and where the sentiment of the country is headed, these are expressions by

citizens, he says, that ought to count if government is going maintain the

trust of the people on wildlife issues.