Back to StoriesProtecting Tranquility One Square Inch At A Time

August 2, 2021

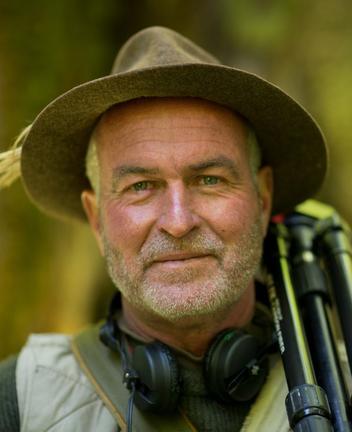

Protecting Tranquility One Square Inch At A Time Escaping the noisy human cacophony: They call Gordon Hempton 'the sound tracker' but he's really a maestro who reminds us that natural harmonic bliss exists in the quietest spots of the Lower 48

By Gordon Hempton

Everyone should be blessed with a place they can call their own—a place where they can feel intimately connected with the rest of life; a place where they can shed, like water off a salal leaf, the cares of a busier, stressful, noisy life back home.

For me, that place is the Hoh Valley of western Washington in the rainforest of the Olympic Peninsula. I discovered it with my ears.

But not initially.

I first walked up the Hoh Valley trail alone the summer before my senior year as a botany major at the University of Wisconsin. This was 1975, and I was taking a summer exchange course on photography at Evergreen State College. I backpacked in with an Olympus OM-2 and plenty of Kodachrome 25, intent on photographing what I’d been told was a spectacular, towering, temperate rainforest.

I took plenty of photos, all right, but looking at them later, I felt frustrated, and didn’t really know why until some six years later, when I returned to the Hoh not as a sightseer, but as a listener, and began to appreciate the rare charm of this secluded valley. This came early in my career as a nature sound recording artist and acoustic ecologist.

Yes, my career is about being attuned to sensual elements of landscapes that are spectacular if we weren't so distracted as to not hear them.

Since then, I’ve circled the globe three times searching for the pristine sounds of nature untrammeled by the noise of man prolifically distributed across every continent but Antarctica. I’ve set up my equipment in every state in the nation and in most of America’s national parks. Sadly, I’m almost always disappointed. Typically, there’s truck traffic from a highway 10 miles away. Or the steady, low frequency hum of a paper mill.

We need quiet places like this to bring us closer in touch with our planet—and also ourselves.... In a profoundly quiet place,, you come to learn there is a wealth of meaning and understanding carried on the musical score of delicate and subtle sounds—natural notes that can be enjoyed only in the absence of manmade noise and only after quieting yourself emotionally as well. These places of tranquility need to be defended.

More and more I find myself listening for something that has vanished, which explains why I keep coming back to the Hoh. Tucked away in a remote, often overlooked corner of the continental United States, in a rare national park unbisected by a roadway, beneath few prescribed jetliner routes, the Hoh Valley remains a listener’s paradise and a national treasure. I believe it’s the quietest spot in the Lower 48.

I know the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and remote places like the Thorofare located in national forest off Yellowstone's southeastern flank are said to be among the most remote in the Lower 48. But remoteness doesn't always translate to quietest, at least for escaping human noise. Where do you go to find nature's symphony?

Fall is my favorite time of the year in the Hoh. Arriving at the visitors’ center parking lot and turning off the engine, the first sound I hear is the tinkling of the motor as it begins to cool. I can be nearly a mile up the trail and still hear the beep-beep of somebody’s remote door lock shouting out the job is done. But step-by-step up the gentle trail the ties to civilization fall away. In the absence of wind and rain, my sound meter has registered in the low 20 decibel range, as quiet as a bedroom at night.

After two miles, you’ll hear the far off hot of owls, even during the daytime. And the sledge-hammer blows of the pileated woodpecker. And the high-pitched twittering cascade of the winter wren, a great favorite of mine. You’ll hear them much more often than you’ll see them, which is why even the best photographs can’t capture the full experience of the Hoh. Sound does not hide behind a fallen tree or a bend in the trail. Our ears take us where our eyes cannot--and in a listening sanctuary like the Hoh, reward us again and again.

About three miles from the visitor’s center begins the rare opportunity for true aural solitude. You’ve passed out of earshot of activities at the camping area at the trailhead and the turnaround point for many day hikers. It’s not uncommon to walk for hours and pass only one or two hikers, generally descending from the mountains after a several-day backcountry experience. They no longer smell like their laundry detergent. Nor are they fretting about things left undone back at home or at work. I love the contented looks on their faces.

At 3.2 miles up the trail, I turn left off the path when I reach a cave-like opening made by a co-joined stilted spruce and hemlock, and soon step through a low muddy area often crisscrossed with elk tracks. I stop when I come to a small red rock atop a chest-high moss-covered log. The stone, given to me years ago by David Four Lines, the late cultural elder of the Quileute Tribe, marks the spot that I’ve designated One Square Inch of Silence—a sanctuary of solitude that I am defending from all human noise intrusions.

We need quiet places like this to bring us closer in touch with our planet—and also ourselves. Living in suburbia and the city, we’ve come to equate the loudest sounds with the most important. We listen to the loudest first. The squeaky wheel gets our attentive grease. But in a profoundly quiet place like the Hoh Valley, you come to learn there is a wealth of meaning and understanding carried on the musical score of delicate and subtle sounds—natural notes that can be enjoyed only in the absence of manmade noise and only after quieting yourself emotionally as well.

These places of tranquility need to be defended. The disruption of natural quiet by jets landing and taking off in Grand Teton National Park, the only national park with a major commercial airport inside it, is well known. In the fall, the noise of aircraft engines is so loud as to muffle the soundscape of bugling elk, or impair the ambiance of a visitor trying to capture the early morning rapture of sunrise. And across the National Park System there are concerns about aircraft presence.

Currently the Navy is escalating training flights of EA-18G Growler jets, one of the military’s loudest, over the skies above Olympic National Park and the western coast of the peninsula. These Navy training flights can currently be heard for 57 minutes on an average day, even deep inside in the Hoh rainforest, according to a recent scientific study.

Similar to an avalanche’s rumbling roar or a devastating earthquake, the sound of EA-18G Growler jets is high-energy, low frequency—simply demanding our attention on the Olympic Peninsula. Our Hoh Rain Forest is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and Biosphere Reserve. Why here?