Back to StoriesThis Is Our Common Place To Celebrate The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

April 24, 2018

This Is Our Common Place To Celebrate The Greater Yellowstone EcosystemMeet here: Mountain Journal may be idealistic but we still believe your voice matters

We are Greater Yellowstoneans. We share an ecosystem and yet often it seems as if we dwell in different worlds.

Consider the differing politics of Wyoming, Montana and Idaho, the three states that converge to form our 22.5-million-acre region. Consider the different community affinities, how the social vibe of Jackson Hole is different from that of Cody or Lander, which, in turn, is different from Riverton and Dubois, which have dramatically different feels from Rexburg and Ennis, certainly distinct from that swelling burg to the north, Bozeman.

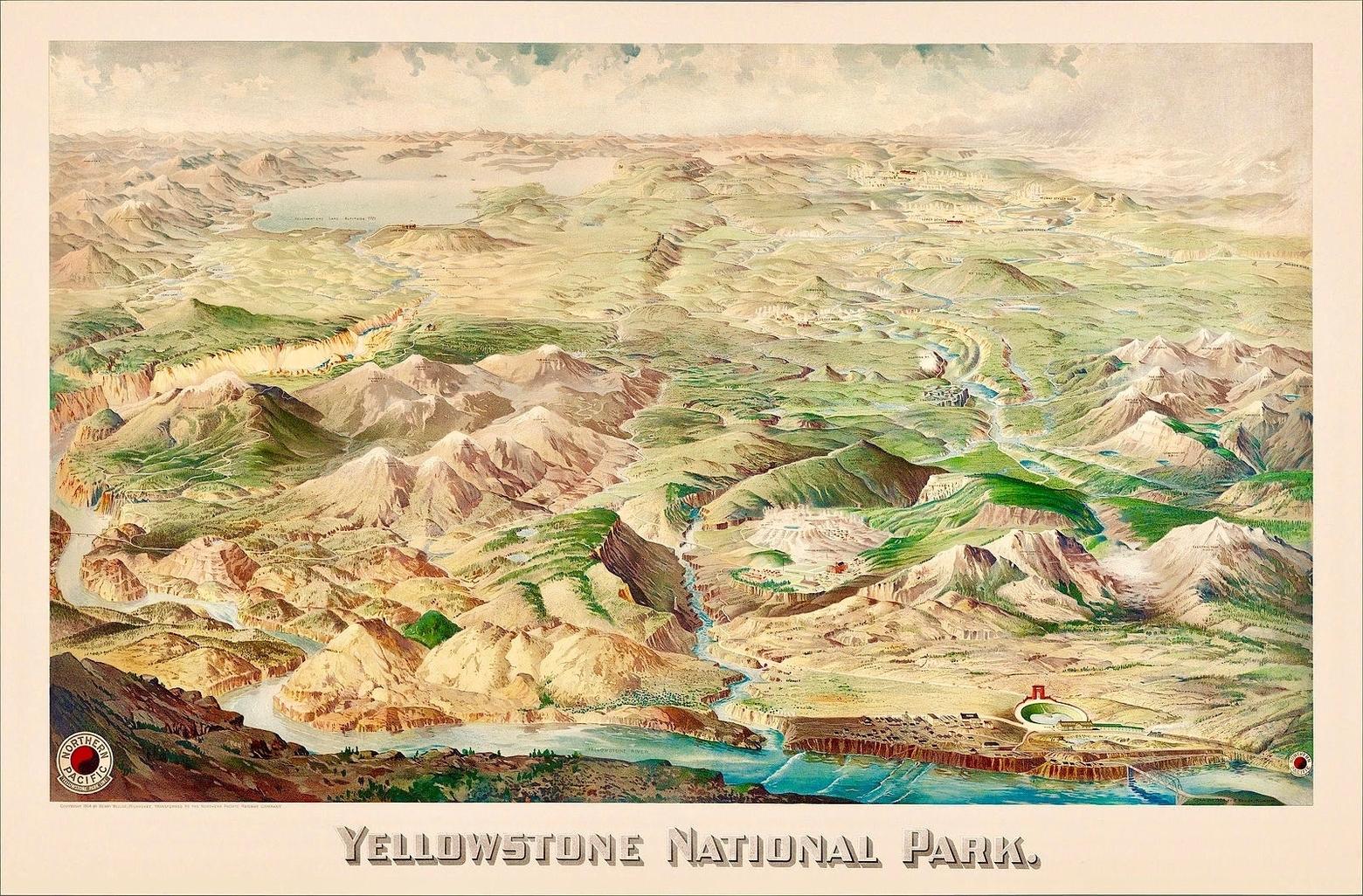

Think of how different a trip to Yellowstone feels versus a traipse around Grand Teton or how distantly remote the Red Desert, located on the south end of Greater Yellowstone, feels from Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge in Montana’s Centennial Valley.

Or how the Crazies are just as much of an obscurity for denizens of Star Valley as the Salt River Range is to those in Red Lodge. Or how the Absaroka-Beartooths, national park-caliber wildlands in Montana, command as much devotion as the Wind Rivers which were once candidates for being a national park.

In my ramblings around Greater Yellowstone these past 30 years, I’ve noticed how it used to seem that we existed further apart. Today, thanks to more enlightened understanding of ecology, commerce and awareness of how things tie together, there is an emerging common identity.

The good abiding news: you don’t have to be rooted here physically to be an advocate for its well-being, because it is a part of our shared heritage, no different from holding a hand to heart and momentarily, at least, setting aside differences to see three converging colors in a flag.

Even though federal land managers long resisted the term “Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem” in favor of “Greater Yellowstone Area” because those in charge thought using the word “ecosystem” sounded too green and therefore unacceptable to politicians or even to their natural resource extraction training in college, our common region possesses a modern centrifugal allure.

The idea of common place has deepened. Mountain Journal, which we founded to explore that connection, today has readers in 190 different countries and people who believe in the value of public-interest journalism, watchdogging a region they love, helping us continue through the generosity of personal contributions.

Like it or not, the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, this vast geographical island of clustered mountains, high plateaus, headwaters for major rivers rising from its interior, wildlife migrations, native trout, unmatched still-functioning geothermal phenomena and a rare caliber of solitude, is unique.

Every Western state has pretty scenery and fine places to play, but none with our wildness. “Unique” is an abused, overused word in our society, though its actual definition means one of a kind, unequalled and unusual.

One thing about we Greater Yellowstoneans and, by extension residents of the three states, is the fact that many of us suffer from myopia. Unless we get out and see the outside world, or rattle ourselves out of the trance of daily sleepwalking, it’s difficult to mentally wrap one’s mind around the truth of how unique Greater Yellowstone really is.

We’ve just spent two human generations resuscitating Greater Yellowstone’s grizzly bear population and now the state of Wyoming wants to sell opportunities to kill individual bears as if hawking trinkets.

We fight over water to grow common, non-native alfalfa in order to feed common non-native beef and we spend a lot of money killing wolves in order to protect said beef on public land when the greatest commodity ranchers own is private land habitat (in all its forms) that keeps our world-class region functioning. Open space. Grass. Clean water. Soil.

The question is how does society reward/compensate/honor/recognize ranchers for the valuable services they safeguard/deliver, that gives them economic peace of mind, self-satisfaction and keeps them—and not residential sprawl— on the land?

We (our often closed-minded county commissions) claim to be fiscal conservatives, yet we allow people to build second, third or fourth vacation homes on the edges of national forests and expect American taxpayers to spend vast sums of money protecting the structures from burning.

Some developers push growth and chastise land use planning and zoning, yet try to wash their hands of responsibility for the negative impacts their projects bring.

Your passion is invited, differences of opinion welcomed, civility required and demanded.

Meanwhile, our state tourism bureaus spend millions, using misleading pictures, touting summer vacations in Yellowstone without reflecting on the reality that no more promotion is needed. Roads already are filled with jarring congestion that is the opposite of the idyll they are selling.

All of the above are just a few of the inspiring, remarkable and disturbing realities converging in America’s wild backyard. They are complicated but not intractable.

What’s missing? A cohesive thoughtful cross-boundary adult dialogue that isn’t being advanced. Not long ago, MountainJournal.org created a group on Facebook called Greater Yellowstone Forum.

It’s not earth-shattering. It’s merely an easy to access “place” to celebrate the things we love about Greater Yellowstone and share good ideas of how to solve problems to existing challenges. Look for it.

Your passion is invited, differences of opinion welcomed, civility required and demanded. If your modus operandi is launching personal attacks, pushing only personal interest ahead of public interest, or you don’t behold Greater Yellowstone with the reverence we believe it deserves, no worries. There are certainly other places for you to wield an opinion.

For the rest, please like the Mountain Journal page on Facebook which you can find at: www.facebook.com/themountainjournal and tell your friends about us. Together we’ve started a groundwell of advocacy for the most unique wild ecosystem in the Lower 48. We still believe your voice matters.