Back to StoriesDoes The E-Bike Invasion Represent A Menace To Wildlife And Character Of Public Lands?

September 25, 2019

Does The E-Bike Invasion Represent A Menace To Wildlife And Character Of Public Lands?In this analysis, Larry Desjardin examines impact of Interior Department executive order opening gate for e-bikes in national parks, wildlife refuges and BLM lands. Are national forests next?

On a sunny afternoon outside of Steamboat Springs, Colorado, I clicked into the pedals of the e-mountain bike underneath me. In front rose US Highway 40 towards Rabbit Ears Pass. To my right was elite triathlete and fellow conservationist TJ Thrasher on his Cervélo competition triathlon bike. I would be racing him up the slopes towards Rabbit Ears Pass to answer the question—could a recreational cyclist, armed only with the lowest class of e-bike, outclimb an elite athlete on his competition machine? And, if so, what are the implications?

° ° ° °

The events leading up to the “E-bike challenge” can be traced back to August 29, 2019 when Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt issued Order No. 3376 with this subject line: “Increasing Recreational Opportunities through the Use of Electric Bikes.”

In that edict, Bernhardt commanded that all land management agencies under the Interior Department consider electric bikes, also known as e-bikes, as non-motorized vehicles and “shall be allowed where other types of bicycles are allowed.” This includes paved roads and dirt trails, the latter igniting immediate resistance from conservation groups.

The breadth of the order is staggering. The Interior Department manages not only national parks and monuments, but wildlife refuges, the Bureau of Reclamation, and the Bureau of Land Management. Of all of the major federal land management agencies, only the US Forest Service, managed under the Department of Agriculture, is free from Bernhardt’s order.

Lost in the debate about e-bike access are the technical, regulatory, and environmental aspects behind the controversy. Without a common base of terms and understanding, it is difficult for proponents or opponents to agree on anything.

E-bikes are bicycles with an integrated electric motor that provide an electric power assist to the operation of the bicycle. The system is composed of a small electric motor, a rechargeable battery, and a motor controller. The system can add power in addition to that put out by the rider (Class 1 and 3 e-bikes add power only when the rider is pedaling), or the e-bike can be exclusively propelled by the motor via a throttle control (Class 2) with no peddling required. E-bikes may be pedaled without power assist, though their heavier weight may discourage many riders from doing so. A typical e-bike will give the rider control over the amount of assist, or “boost,” available from the bike through a control on the handlebar.

The unilateral dictate from Bernhardt puts the character of wildness still present in public lands into uncharted territory and many worry it represents a slippery slope, enabling large numbers of people to motor faster, deeper and longer into terrain they wouldn’t ordinarily access. Equally disturbing is the method of Bernhardt’s announcement- a declaration without any public comment or even a cursory NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) assessment. Considering that many of the trails in question were approved only after a NEPA analysis that assumed a prohibition of all motorized vehicles, including e-bikes, Bernhardt’s edict strikes at the very heart of the National Environmental Policy Act and its role in protecting our public lands.

Driving the advancements in e-bike performance is the lithium-ion battery serving as the power source. E-bikes profit by leveraging the same battery technology being developed for electric cars and hybrids. A key specification for EV (electric vehicle) batteries is the gravimetric efficiency, essentially the energy capacity to weight ratio of the battery source, measured in watt-hours per kilogram. This key specification has been improving by an impressive 5-8 percent per year, as battery manufacturers race to capture a share of the increasingly lucrative EV battery market.

Driving the advancements in e-bike performance is the lithium-ion battery serving as the power source. E-bikes profit by leveraging the same battery technology being developed for electric cars and hybrids. A key specification for EV (electric vehicle) batteries is the gravimetric efficiency, essentially the energy capacity to weight ratio of the battery source, measured in watt-hours per kilogram. This key specification has been improving by an impressive 5-8 percent per year, as battery manufacturers race to capture a share of the increasingly lucrative EV battery market.

The battery capacity determines how much power an EV can apply, and for how long. The same is true for e-bikes. As new lithium-ion technologies are commercialized, constraints on the power and range of e-bikes recede.

Setting aside the controversy over Bernhardt’s order, e-bikes have a promising future in urban transportation solutions. For many people, e-bikes make commuting and performing errands via a bicycle feasible. With that behavior change comes reduced traffic congestion, more parking options, and a smaller carbon footprint. Cities that have a significant bicycle portion in their transportation mix, such as Amsterdam or Copenhagen, are often flat. Wheeled transportation is efficient on level terrain, but any rise in elevation requires the combined weight of the rider, the bicycle, and all transported items to be lifted by the effort of the rider. E-bikes, with their embedded motors, eliminate that constraint.

The emergence of e-bikes was a conundrum for state and federal regulators. They are clearly motorized vehicles, but should they be licensed and registered the same as the family car? Eventually, most states allowed their use without registration or the rider having a driver’s license as long as the power applied would not exceed one horsepower, which later was approximated by 750 watts. This was subsequently codified nationwide through the Consumer Product Safety Act, which defines a “low speed electric bicycle” as including a “two- or three- wheeled vehicle with fully operable pedals and an electric motor of less than 750 watts.”

Additional restrictions are dependent on the class of the e-bike. The three classes are:

- Class 1: Bicycle equipped with a motor that provides assistance only when the rider is pedaling, and that ceases to provide assistance when the e-bike reaches 20 mph.

- Class 2: Bicycle equipped with a throttle-actuated motor, no peddling required, that ceases to provide assistance when the e-bike reaches 20 mph.

- Class 3: Bicycle equipped with a motor that provides assistance only when the rider is pedaling, and that ceases to provide assistance when the e-bike reaches 28 mph.

All classes limit the motor’s power to 750 watts. Interestingly, the European Union has adopted the same classes, but limits the power to 250 watts. Canada has adopted a 500-watt limit. These power limits are critical to understanding the impacts to wildlife when e-bikes are allowed to traverse sensitive habitat.

Bernhardt’s order is often defended as a way to allow those with disabilities to enjoy mountain biking with their friends and family. Indeed, the order reads, “Reducing the physical demand to operate a bicycle has expanded access to recreational opportunities, particularly to those with limitations stemming from age, illness, disability or fitness, especially in more challenging environments, such as high altitudes or hilly terrain.”

The “hilly terrain” describes nearly any backcountry hike in the Rocky Mountains, and the preponderance of multiuse trails in the forests. The question is, at these power levels, are e-bikes principally designed to help the disabled, as proponents claim, or to enable superhuman capabilities for anyone who desires it? The 20 and 28 mile per hour boost limits were created to limit the performance of the machines when they were envisioned to be used on urban bike paths or a public highway. But, are these speed limits even relevant for terrain with steep uphill ascents?

° ° ° °

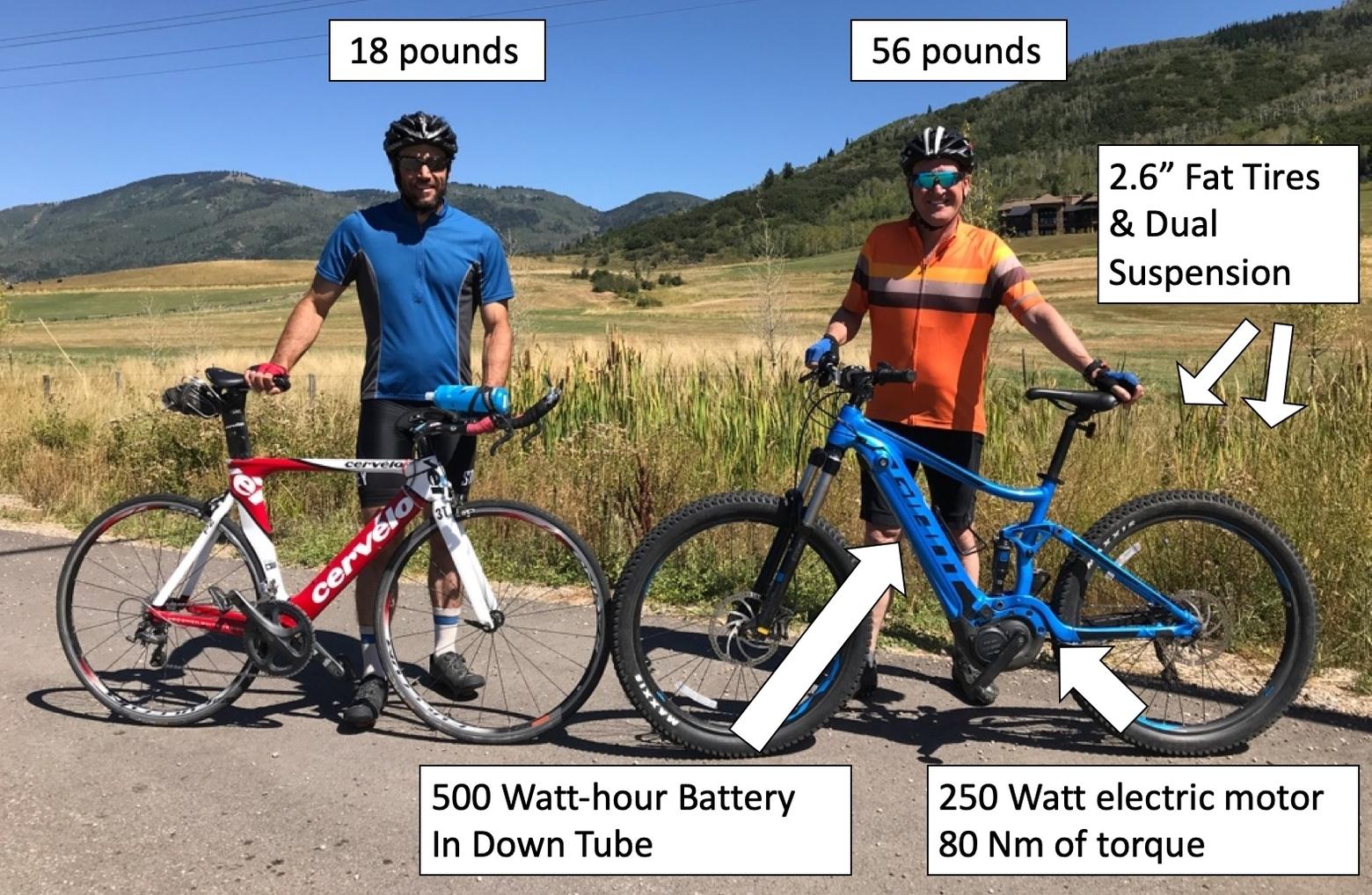

Thus, the E-bike Challenge. Being a recreational cyclist and a bike geek, I decided to rent one and see for myself. I headed down to Steamboat Ski and Bike Kare, where they matched me with an e-MTB (electric mountain bike), the Giant Stance E+2. The Giant is a Class 1 e-bike with a 250-watt Yamaha motor. It is a mid-level e-MTB, targeted at beginner and intermediate riders. I was disappointed that the newer 500-watt e-MTBs weren’t available for rent, particularly when I lifted the massive 56-pound frame onto my bike rack. At this weight, adding power assist becomes a near necessity for riding uphill. Nevertheless, I started planning how I would give it a test.

That’s when I got a call from TJ Thrasher, a fellow board member on our local conservation group. TJ is also an elite triathlete and has completed several Ironman-length triathlons. “Let’s race!” said TJ, and soon we had a plan. We would race “hill sprints” up the 7 percent grade to Rabbit Ears Pass, he on his competition 18-pound Cervélo triathlon bike and me on my 56-pound rental fat tire e-mountain bike. We were both curious what the results would be, particularly with the modest power of my rented e-bike.

Another friend, equipped with only an iPhone and a Vespa motorscooter, agreed to document the challenge. That is how I found myself, a recreational cyclist, rolling my rented e-bike into position next to TJ’s race machine.

° ° ° °

TJ and I are recent friends, having met only in the past year as board members of the newly created conservation group, Keep Routt Wild. Routt is the name of our County, and home to Steamboat Springs, a mountain town in northwest Colorado. We face many of the same challenges as those of the Greater Yellowstone Area. Our group formed spontaneously in opposition to the proposed “Mad Rabbit” Trails Project, a massive network of largely multiuse trails planned to crisscross Routt National Forest.

Based on a rich set of peer-reviewed scientific studies quantifying the impact of recreation on wildlife, and our local elk herd in particular, we’ve argued the case for the elimination or re-routing of many of the trails. The US Forest Service has subsequently proposed a more modest plan, and we continue to engage with them on this issue.

Those scientific studies are key to quantifying the impact from recreational activities, particularly hiking, horseback riding, mountain biking, and ATV use. They also lend crucial insight when e-bikes are added into the mix. Many of the studies focus on the specific impact to elk, a migratory animal serving as an umbrella species for much of Colorado. The E-2 “Bear’s Ear” elk herd of Routt National Forest is the second largest elk herd in Colorado, making it also the second largest elk herd in the world. Two studies highlight the impact of recreation on elk.

The first study took place to our south, near Vail, Colorado. Colorado State University researchers Gregory Phillips and William Alldredge measured the impacts to elk calf survival rates from simulated recreational hiking. During calving season, a radiocollared cow elk would be approached until she was “displaced”, essentially fleeing. Each event counted as a disturbance. The study showed elk calf/cow ratios declined by approximately 40% as a result of this human disturbance. The second half of the study involved removing the human disturbance component. With the human disturbance removed the calf/cow ratios rebounded to their pre-treatment levels.

The Phillips study averaged eight disturbances per cow elk to result in 40% fewer surviving calves, or about 5 percent mortality per disturbance. This is a remarkably high mortality rate from a single disturbance. The researchers speculated that the high mortality rate was largely due to predation- that each disturbance of the cow elk also led to the calf fleeing or being unprotected. While the research quantified the impact of human disturbance, it didn’t quantify what recreation activities create a disturbance, or from what distance from a trail.

However, a study a few years later in Oregon would do exactly that.

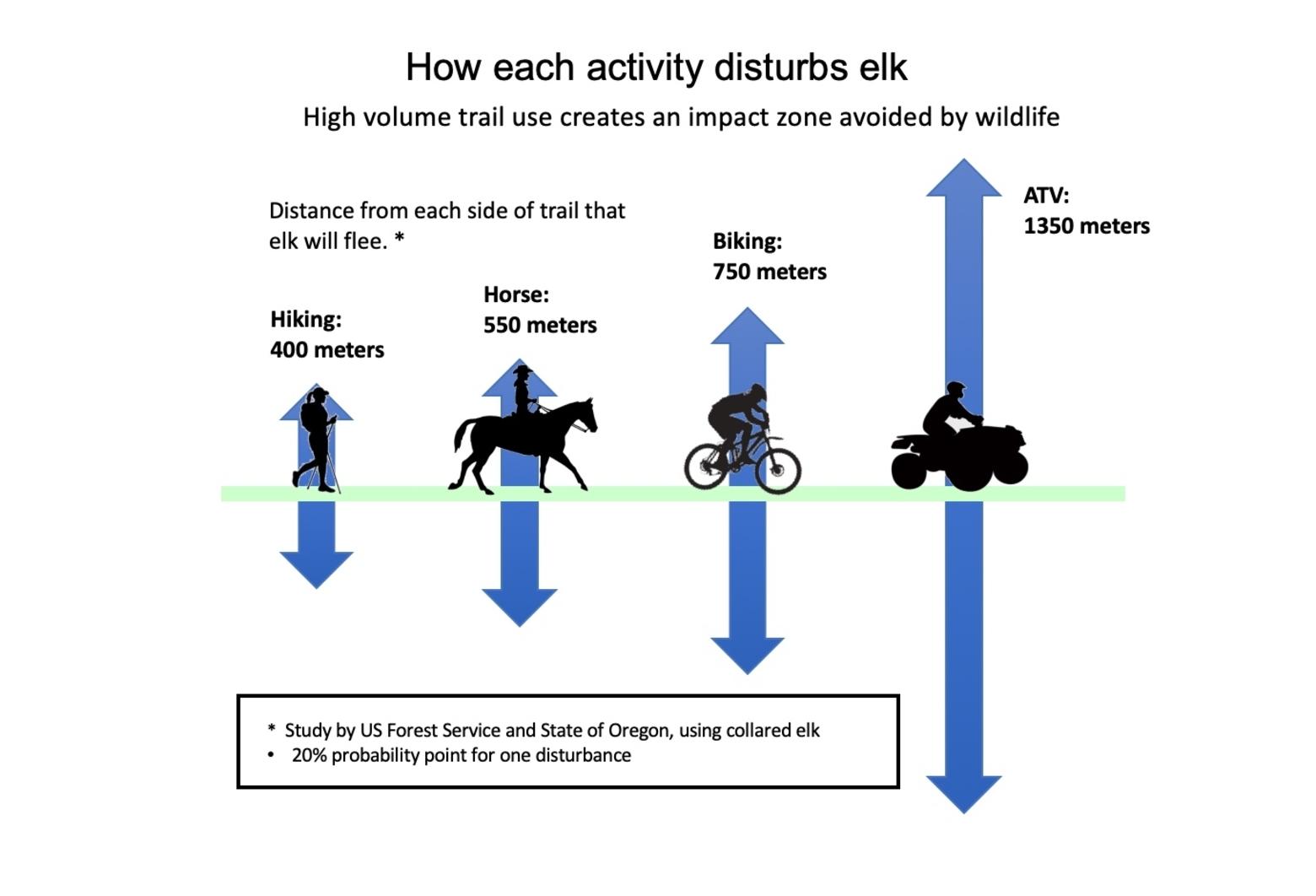

That study, often referred to as the “Wisdom study” led by US Forest Service biologist Mike Wisdom, placed radiocollars on mule deer and elk within an enclosed area in eastern Oregon, and then subjected the ungulates to specific recreation activities- hiking, horseback riding, mountain biking, and ATVs. By looking at a large number of radiocollared animals, they could model the probability that the animals would flee, and at what distance, for each specific activity. This “fleeing” corresponds to a disturbance in the Phillips study.

The results were eye opening. The results showed, specifically with elk, a wide disturbance distance from the trail, with the results varying with activity. “We saw that their flight response occurred at distances over 1000 meters (3,218 feet) for ATVs and close to that for mountain bikes, and more like 500 to 750 meters (1,640 to 2,460 feet) for horseback riding and hiking,” Wisdom said. In the September 2019 issue of PNW Science Findings, a publication of the US Forest Service, the researchers articulated additional concerns that go far beyond those during calving season. Chief among these is habitat compression.

The publication reads, “avoiding motors, wheels, hooves, or feet takes a toll on elk in two ways: increased energy expenditures and decreased access to food sources. Moving more than necessary and not having enough to eat can be detrimental to the viability of elk populations. For example, if females don’t put on enough body fat, they may not be able to reproduce.” It continued, “output from the elk “Fitbits” showed that the animals spent less time feeding and resting and more time running compared to when there was no human activity. And the amount and quality of forage area available to the animals shrank as they shifted away from recreation trails.”

“You’ve basically reduced what we call carrying capacity, the number of animals that can make a living on the landscape,” Wisdom summarized.

In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, many biologists worry about the same impacts on the region’s famous wapiti herds as well as on grizzly bears and other species. The Wisdom study subjected the animals to a specific recreation activity twice a day. Even with this low level of disturbance, elk were prone to stay away from the trails used. Notedly, the study didn’t quantify the potential additional impact of industrial strength tourism campaigns loading the trails with users from dawn to dusk, and increasingly beyond. If the modeling shows a 50 percent chance of elk fleeing from a single disturbance at a specific distance, what is the impact to a hundred such disturbances daily?

For this reason, wildlife managers often use a lower threshold than 50 percent to determine the disturbance zone around a specific trail and a particular activity. Figure x shows the disturbance width from the Wisdom study of each activity when the threshold is set at 20%.

An interesting correlation from the Wisdom study is speed. Each successively faster activity comes with a wider disturbance zone. A likely explanation is that speed reduces the time an animal has to react, and a surprised animal is more likely to flee than hide. This is consistent with findings from grizzly bear biologists quoted in a recent Mountain Journal article, including Dr. Christopher Servheen.

Servheen, retired from government service, spent four decades at the helm of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Grizzly Bear Recovery Team in the West. He is an adjunct research professor in the Department of Ecosystem and Conservation Sciences at the University of Montana. “High speed and quiet human activity in bear habitat is a grave threat to bear and human safety and certainly can displace bears from trails and along trails,” Servheen said. “Bikes also degrade the wilderness character of wild areas by mechanized travel at abnormal speeds.”

That same article quotes wildlife research consultant A. Grant MacHutchon, who analyzed risks of human-bear interactions near Jackson Hole, “Mountain biking is often characterized by high speeds and quiet movement. This limits the reaction time of people and/or bears and the warning noise that would help to reduce the chance of sudden encounters with a bear. An alert mountain biker making sufficient noise and traveling at slow speed (e.g. uphill) would be no more likely to have a sudden encounter with a bear than would a hiker. However, on certain types of trails (e.g. flat, moderate downhill, smooth surface), the typical bicyclist can travel at much higher speeds than hikers, which increases the likelihood of a sudden encounter.”

If speed is a key attribute of activities that disturb wildlife, then what would be the effect of allowing electric bicycles on those same trails? Are they slow, plodding machines, created to help those with disabilities? Or are they increasingly powerful electric motorcycles destined to break uphill speed records?

The moment of truth arrived. We would find out.

The moment of truth arrived. We would find out.

° ° ° °

Setting my rented e-bike to maximum boost, TJ and I both peddled softly until the grade turned decidedly uphill. Looking back at me, he said “Let’s go!” And then we hammered.

For accuracy, I should say TJ hammered. My 64-year body doesn’t “hammer” these days. My typical method of riding this climb is to shift into my lowest gear and stay there for the next hour and fifteen minutes. TJ, on the other hand, immediately output an explosive 650 watts into his pedals, measured by his embedded power meter. I stood on my pedals, hoping that my own peak power, probably half that of TJ’s, would add to the e-bike’s power to keep me in touch with him. I was also riding a bike that weighed three times that of TJ’s.

No athlete can sustain TJ’s initial 650 watts, including TJ. Compare his power output to that of Tour de France cyclist Thomas De Gendt. De Gendt shared his ride data on Strava after winning the prestigious 2016 Mont Ventoux stage. His average power output over the entire ride was 319 watts, with a peak power output of 1,046 watts. A Class 1 e-bike ridden by a recreational cyclist could shatter both figures.

I stayed within a few bike lengths of TJ as he faded to a “mere” 300-something watts, still more than Thomas De Gendt’s average. Suddenly, to my surprise, I was gaining on him. The distance closed rapidly as I raced up the slope at three times my typical climbing speed. Sitting comfortably on my fat tire mountain bike I reached TJ, who was furiously mashing the peddles on his race bike. I slowed my pace to give him words of encouragement before I accelerated up the climb alone to our improvised finish line. The e-bike had won the challenge.

We repeated the test three times, all with the same results. A 56-pound run-of-the-mill e-mountain bike with only 250 watts of power had enabled me to beat an elite athlete up the grade.

Imagine what 750 watts, the limit for the lowest class of e-bikes, Class 1, would have shown.

° ° ° °

This experiment reveals the flaws in using the current set of e-bike classifications for off-road use. The current classes control the performance of an e-bike by a speed limit set in the controller, above which power won’t be applied, and only the power of the cyclist can bring the speed higher. This may be an effective method to control the power applied on a flat city bike path or a two-lane highway. But when the path turns decidedly upwards, and the 20-mph limit is never reached, the full power boost is retained.

Now consider e-bikes in the context of MacHutchon’s comments about speed. The low speed that characterizes mountain bikes going uphill will be a thing of the past if e-bikes are introduced. Essentially, even Class 1 e-bikes will be able to reach 20 miles per hour regardless of the grade of trail, or the direction. Increase that to 28 miles per hour as Class 3 e-bikes are introduced. If grizzlies and other wildlife are disturbed by increased speed, e-bikes will enable this speed for all trails, all sections, up or down, all the time.

This will be the impact from Bernhardt’s order if it stands.

Many of the proponents for allowing e-bikes on trails claim e-bikes will help people with disabilities enjoy the same terrain as able-bodied mountain bikers. This is a valid concern and could be addressed by a targeted policy which includes specific labeling and performance constraints of the e-bikes offered. But that isn’t what the e-bike industry is about or where it’s going. It’s about offering superhuman capabilities to ordinary riders. Otherwise, why not adopt Europe’s 250-watt limit in the United States? Why 750 watts?

Don’t take my word for the “superhuman” capabilities being targeted and marketed by the bike industry. Just look at the advertisements from major bike manufacturer Specialized describing their line of Turbo e-bikes. "Combining speed and style through an innovative pedal-assist motor, advanced electronics, and a sleek design, our Turbo e-bikes represents the full capabilities of the e-bike revolution. They're capable of achieving top speeds of 45 Km/h while you pedal, so they'll deliver near superhuman power to any rider."

Specialized recently promoted the elite performance capabilities of e-bikes with a video advertisement featuring Tour de France superstar Julian Alaphilippe. In the ad, Tour de France announcer Phil Liggett is announcing that Alaphilippe, shown climbing, is in pain and in trouble. Soon, Phil Liggett himself shows up, microphone in hand, passing Alaphilippe on a Specialized e-bike. Their tagline? “It’s Julian, Only Faster.”

"...in an age of recreation everywhere all the time, and now without limits, is there still room for an elk to raise her calf, or a grizzly sow to teach her cubs? In this future world, is there even room for a hiker to peacefully stroll on our public lands without being hazed by a line of electrified motorcycles? Bernhardt's order is leading us in that direction."

One must wonder where this ends. Is the goal of the e-bike industry that all of us should be able to perform on the level of a Julian Alaphilippe or the equivalent elite mountain biker? Are we redefining disability to mean any athletic performance under that of the most elite athlete at the time?

More importantly, in an age of recreation everywhere all the time, and now without limits, is there still room for an elk to raise her calf, or a grizzly sow to teach her cubs? In this future world, is there even room for a hiker to peacefully stroll on our public lands without being hazed by a line of electrified motorcycles?

Bernhardt’s order is leading us in this direction. The concept of “multi-use” trails, where hikers, bikers, and horses share a common path may be a casualty of this decision. If wheeled recreation means allowing electric motorbikes wherever mountain bikes are now allowed, then it might be time to reconsider the entire package.