Back to StoriesWhen Wild Nature Enters Our Dreams

People dream big in this rough world of the American West, in daydreams before we arrive, after we get here and with how we move through it—whether in ascending a mountain, skiing a couloir, whitewater kayaking or soaking in a sunset. In night dreams, apart from potential real encounters in the light of day, we sometimes confront grizzlies, wolves, elk and bison.

February 28, 2021

When Wild Nature Enters Our DreamsFrom visions to daydreams to the imagery that visits us in slumber, dreamscapes can reveal much about ourselves and how we're navigating the world

by Timothy Tate

People dream big in this rough world of the American West, in daydreams before we arrive, after we get here and with how we move through it—whether in ascending a mountain, skiing a couloir, whitewater kayaking or soaking in a sunset. In night dreams, apart from potential real encounters in the light of day, we sometimes confront grizzlies, wolves, elk and bison.

What role do dreams play in our life and how might we implore their wisdom as we sleep in our tents, bivouacs, and bedrooms in towns that are often interwoven into a fabric of wild nature?

The practice of psychotherapy in communities like ours is informed by the grand landscape that summons adventure, discovery and risk-taking. Unlike a counseling practice situated in a Midwestern town’s strip mall, which looks like every place else, what some treat as Greater Yellowstone’s natural playground is but one hike from our front doors.

I can tell you based on conversations I’ve had for four decades and what I’ve learned from my indigenous friends: Mountains have called dreamers to their summits for millennia seeking personal vision. Be it pondering who we are in rarefied air or asking our subconscious self to deliver a dream that will give us a sense of purpose, I believe all of us are seekers pursuing answers to life’s questions.

I can tell you based on conversations I’ve had for four decades and what I’ve learned from my indigenous friends: Mountains have called dreamers to their summits for millennia seeking personal vision. Be it pondering who we are in rarefied air or asking our subconscious self to deliver a dream that will give us a sense of purpose, I believe all of us are seekers pursuing answers to life’s questions.

What we call Livingston Peak in the Absarokee Mountains rising above the river town along the Yellowstone, was a sacred place for chiefs and warriors to fast for a vision, as was Crazy Peak in the Crazy Mountains.

As a homework assignment, learn more about the vision of Crow leader Plenty Coups who foresaw a shift coming between the real human Old West as it existed across thousands of years, and the frenzied New West in which nature has been altered in ways beyond the pace of natural transition.

The book, Black Elk Speaks recounts the spiritual leader's vision on the banks of the Tongue River outside Miles City, Montana, as he suffered through fever and illness near Fort Keough. Black Elk was there at the Little Bighorn River when George A. Custer and members of the Seventh Cavalry fell. He also was close by during the nightmare slaughter of Wounded Knee in 1890.

Dreams—waking and not—can come in monumental forms. They can give us insight into our daily lives, speaking to one’s perceived calling or lack thereof. We can wake from them stunned or sometimes they’ll rattle around awhile before we crack the code.

I was a child dreamer imagining, during sleep, travels with my parents to foreign shores during late adolescence. I had been introduced to a world my child’s brain could not grasp in whole awareness but it was experienced. It involved steamships of travelers crossing the Atlantic Ocean, steam trains crossing Scotland’s lush and foreboding highlands and a soon to be divided Berlin in post-war reconstruction in 1956.

Our psyche—what refers to our soul, mind and spirit— needs a way to conceptualize and integrate content beyond the pale of our daily experience.

We turn to our nightly dreams to behold in images and stories what our brain otherwise fumbles. Some believe the characters who visit in us in dreams are versions of ourselves. Some believe that dreams are ways of working on personal insecurities, trust issues, losses and failures.

Classic dream and sleep studies help us realize the value of dreams. Psychologist Tore Nielsen, director of the Dream and Nightmare Lab at the Sacre-Coeur Hospital in Montreal states: “As soon as you start to rob them [patients] of REM, the pressure for them to go back into REM starts to build.”

Tell me, have you lost sleep during these times of Covid? Have you, too, been restless? And, it should be noted, when we are not having sound sleep our dream time too is interrupted.

Dreams in some ways are like the downtime when a computer server goes offline for maintenance, to clear out the digital bugs and tracking “cookies” that are accumulated as we move through cyberspace. When people are getting enough sound regular sleep and their dreaming is happening, they tend to have more resilience.

What Nielsen meant is that dreams are good for us, good for our health and they can help us move through periods of transition, times of crisis and in confronting our own existential certainties. You can feel as though you’re dying in a dream but you can awake from it relieved that you’ve been given a second chance.

There are four types of dreams. The first kind happens in your initial REM cycle some 90 minutes after falling asleep. It helps the brain release the daytime drama. The second dream cycle may offer a four part dream that tells a story of the state of your personality. The third dream type is the visionary kind like “I had a dream…” of MLK, that either informs humanity or the individuals' higher calling. It could deliver epiphanies.

The fourth type of dream is the recurring one that tells recounts and repeats the origins of your shame patterns.

It was after I completed my Master’s in Counseling at Boston University that the value of dreams became clear. A colleague of mine, who taught sociology while I was teaching psychology, gave me Carl Jung’s autobiography Memories, Dreams, and Reflections. I remember opening the book and descending into his account of the seminal dreams of his young adulthood stirring a feeling like when I catch sight of someone I love.

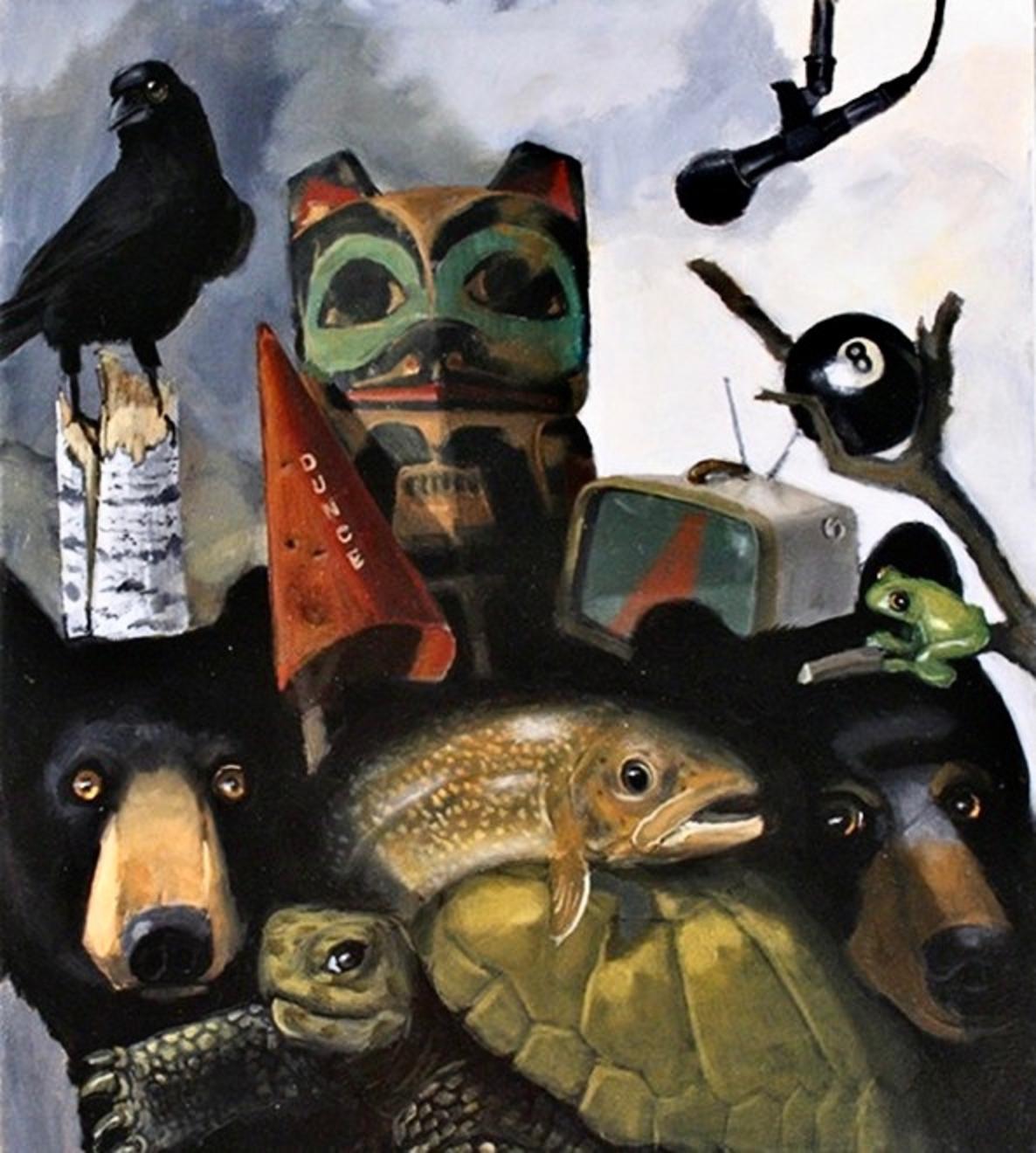

The flora and fauna of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem provide lush context for and encounters with alpha predators. They can be potent symbols for Westerners going back who knows how long, taking the form of pictographs and petroglyphs, in the rituals of name taking or adorning a lodge.

Identifying with animals is part of our personal journey and it exists as a stark counterpoint to using animals as commercial iconography, as magnets for generating profit which is fundamentally an outward experience as compared to an inner, intimate one with self.

Grizzlies, wolves, mountain lions, coyotes, badgers and wolverines challenge dreamers to face forces within their psyche. Meaning is individualistic and it might take a lifetime to understand what the recurrence of an animal, visiting us in dreams, means before we head off into the eternal dream.

What I have found is that we derive greatest insight not in achieving exactitude in the symbolism of dreams but our willingness to internally reflect, to have dialogs with ourselves that lead us to realize we are not trapped but given choices which enable us to expand our view—to be empathetic to ourselves, to other humans and to other species.

What I have found is that we derive greatest insight not in achieving exactitude in the symbolism of dreams but our willingness to internally reflect, to have dialogs with ourselves that lead us to realize we are not trapped but given choices which enable us to expand our view—to be empathetic to ourselves, to other humans and to other species.

Women in my practice tend to dream about bear and wolf encounters more than men. This excerpt is from a woman in my practice who later went on to achieve a doctorate in Depth Psychology.

“The house had a passageway to the wilderness. We were sent out through the passageway. Once in the wilderness I sensed that the path was gently sloping downward and there was a rock wall to the right and a dense forest to the left. There was another woman with me, behind me. I sensed other women had been here before. It was a ritual of sorts. It was my turn to slay. We were scantily dressed or not dressed at all. I had weapons at my disposal. A black wolf came charging at me with its yellow teeth, growling. I had something and hit it. Then I held a staff with an arrowhead. The wolf was charging and charging. I wounded it but it kept coming. There was blood on me. It came at me, and then with all the force within me, I jammed the weapon into its open mouth when it charged at me.”

Dreams like this can propel the dreamer beyond the tyranny of the ego (our own strive for self-importance which is connected to self-esteem, and conversely insecurity) into the imaginal.

Self-care, self-love, self-forgiveness are vitally importance in helping one realize they are worthy of being loved.

This is different from being self-centered, believing that everything in the world, everything that I might extract from the nature of this region, revolves around me.

When you are liberated from acting solely on ego, you realize a wider range of positive possibilities and it lays the groundwork for feeling more connected to the world around you. And, with this, I can mention a fifth kind of dreams—that which leads us to transformation and shedding burdens that we still drag forth but need to let go of.

I extend an invitation to the readers of Mountain Journal to spend a month setting the intention to remember dreams and writing them down. Are we visited by different symbols in the West where we live side by side with a deeper degree of wild imagery?

Remembering dreams allows us to know another dimension of our lives that otherwise disappears into the fog of daily life. Who doesn’t want to use their imagination to make the best of a seemingly bad situation?

Dream, dream on.