Back to StoriesElk in Crazy Mountains Test Negative for Brucellosis, Easing Livestock Concerns

March 3, 2025

Elk in Crazy Mountains Test Negative for Brucellosis, Easing Livestock ConcernsAgency, state officials complete latest surveillance effort in Montana's ongoing battle against wildlife-livestock disease

by Sophie

Tsairis

In late

January, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks conducted operations in the Crazy

Mountains northwest of Big Timber, Montana, capturing elk and testing them for

brucellosis. As part of an ongoing surveillance project, the team secured 52

elk, fitting 16 animals with GPS tracking collars to monitor movement patterns.

While positive tests for the highly contagious disease have increased over

recent years, FWP’s laboratory results from the Crazies showed all sampled elk

tested negative for the disease, indicating no detected exposure in the herd.

The

testing is the latest from the Targeted Elk Brucellosis Surveillance Project, a

collaboration between FWP and the Department of Livestock created in 2011 to

monitor and understand the spread of brucellosis among elk populations, and to correctly

delineate the geographical distribution of the disease. Exposure detection in

two elk near Greeley Mountain and McLeod Basin in 2016 made sampling in the Crazy

Mountains a priority, as did the large presence of livestock in the area.

The

negative results in the Crazy Mountains have wildlife researchers fairly

confident that elk there have not been exposed to brucellosis and do not pose a

disease transmission risk to livestock, providing crucial reassurance for the

region’s cattle industry.

“Test data from live elk captures inform brucellosis

management decisions in Montana,”

State Veterinarian Tahnee Szymanski said in a February 13 press release. “These

negative test results are valuable to Montana’s livestock industry as they help

provide confidence to our trading partners about the quality and strength of

our state program.”

The Greater

Yellowstone Ecosystem has battled the chronic presence of the infectious

disease threatening wildlife and livestock since 1917, when it was first found

in the region.

Historically,

surveillance for the disease across the GYE largely relied on collection

samples from hunter harvested animals, making it difficult to obtain large

enough sample sizes from Montana elk to inform state management decisions. To fill

this gap in data, the project focuses on elk herds near the boundaries of

Montana's designated surveillance area — the region identified as having elk

exposed to brucellosis. Since its inception, researchers have conducted

targeted sampling on 24 different elk herds, with 10 of those herds testing

positive for brucellosis exposure.

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem has battled the chronic presence of the infectious disease threatening wildlife and livestock since 1917.

Jenny Jones, research technician for FWP told Mountain

Journal it’s important to note that brucellosis exposure is determined by

the detection of antibodies to the disease. It is possible that an animal testing

positive is not actively infected—it may have cleared the disease, or it could

be dormant.

Jones said researchers aim to capture around 100 elk from

each herd. “If prevalence is greater than or

equal to 3 percent, then by sampling 100 elk there is a 95 percent chance of

finding at least one exposed animal,” she said.

The surveillance operations, primarily funded by

the Animal Plant Health Inspection Service with additional support from the

Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, involve intensive field work during Montana's

winter months. Each January and February, contracted helicopter teams pursue

elk across snowy landscapes, netting individual animals for testing.

Helicopters allow researchers to catch approximately

25 elk per day in a short amount of time from a specific area. Once captured,

the animals are blindfolded and hobbled before the researchers take blood

samples and attach GPS collars to selected individuals. But because elk herds

often winter on private property, the scientists need help from willing private

property owners.

“Capture

operations would not be possible without assistance and permission from

numerous landowners,” Jones said.

The collars, typically applied to approximately 30

of the elk captured, provide critical hourly movement data that reveals

migration patterns and potential transmission risks. The data serve multiple

purposes beyond disease surveillance, helping biologists understand seasonal

range use and informing hunting quotas and district boundaries.

The primary driver of this extensive surveillance

effort is the risk of transmission from elk to cattle. Jones said she is not

aware of any cases of bison spreading the disease to cattle. The perceived threat has

been a controversial focus for ranchers during ongoing wild bison management

decisions.

“The

main concern is elk to livestock, which is predominantly cattle with a few

bison ranches as well,” Jones said. “Most cases of livestock infection have

traced the initial transmission to elk.

Wild bison are not generally allowed in Montana, while elk movement is

unrestricted.”

For Montana's cattle industry, a brucellosis

outbreak carries severe consequences, including extensive testing, quarantine

and potential loss of livestock.

“There is no treatment for wildlife or livestock,” Jones

said. “There are vaccines administered to livestock but as with all vaccines

they are not 100 percent effective. Livestock that test positive are euthanized

and the remaining herd is quarantined.”

The disease also poses health risks to humans,

particularly dairy workers and hunters who may encounter contaminated fluids or

tissues. Human brucellosis typically presents as a flu-like illness with

fatigue but if left untreated can lead to long-term conditions like arthritis,

recurring fever and memory loss, according to the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention.

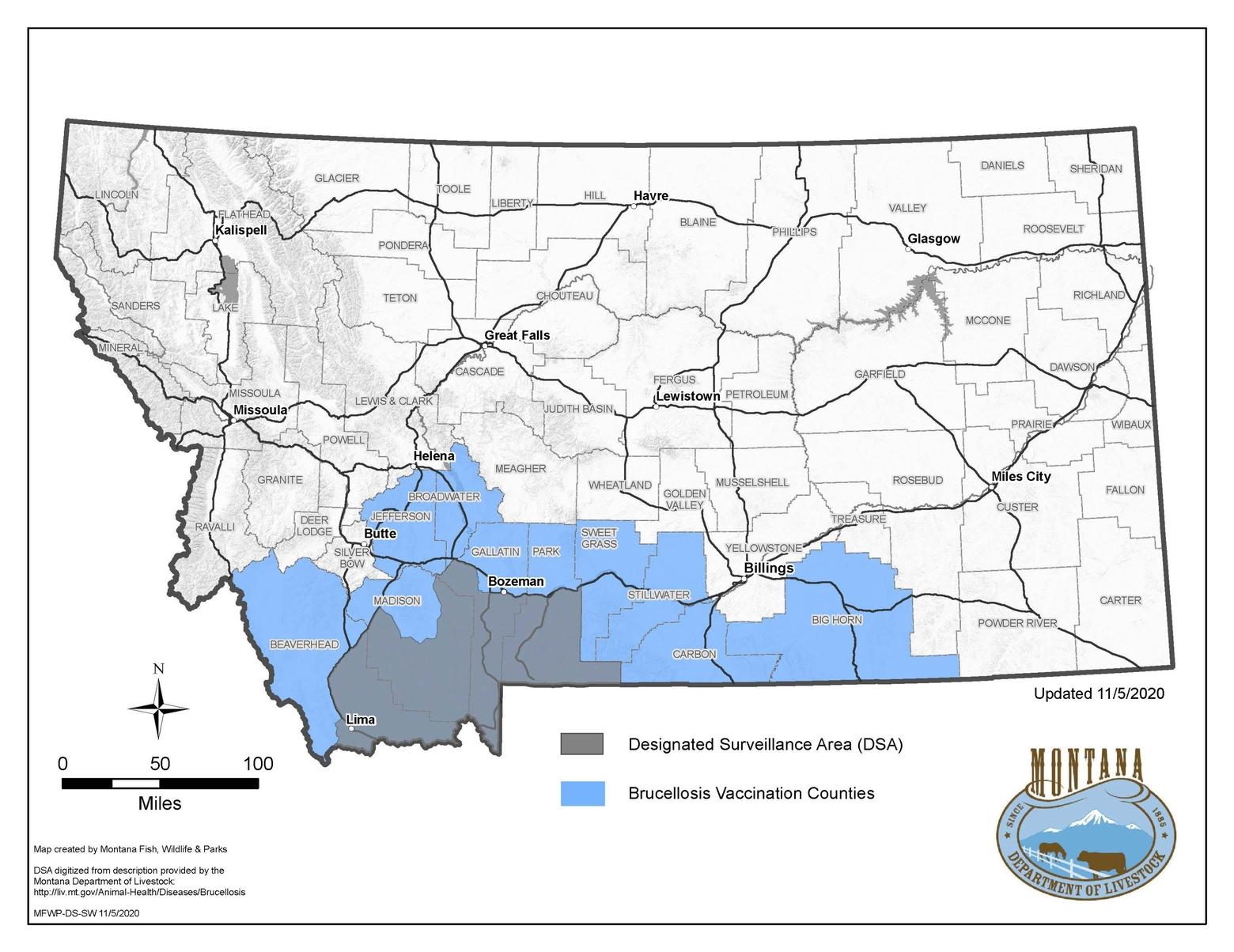

Since 2010, when Montana created the designated

surveillance area, or DSA, its boundary has been expanded five times based on

surveillance results showing exposure in previously unaffected areas. These

adjustments, recommended by the Department of Livestock and approved by its

governing board, help maintain Montana's brucellosis-free status for interstate

livestock trade while acknowledging the disease's continued presence in

wildlife.

“Most cases of livestock infection have traced the initial transmission to elk. Wild bison are not generally allowed in Montana, while elk movement is unrestricted.” – Jenny Jones, research technician, FWP

Szymanski said it’s a big lift for

producers who run cattle operations in the DSA. State requirements mandate that

cattle over 12-months in age that are sexually intact must have a negative

brucellosis test if they leave the DSA. She said 95,000-100,000 animals are

tested in Montana every year.

“We’ve had 13 affected livestock herds since the

inception of the program,” Szymanski said. “It’s not that there are a

substantial number of herds affected, but the reason we do the wildlife

surveillance is to know where are on the landscape seropositive elk are and

where livestock would be at risk for transmission. It’s how we decide our

programmatic requirements.”

Brucellosis

cases in cattle are managed by each state’s Department of Livestock. Jones said

that while some limited information is shared with FWP and the public, such as

the county in which infection is detected, specific information is

confidential.

“Wyoming

and Idaho also have their own DSAs,” Jones said. “Some of the boundaries align

along the state boundaries, primarily, because brucellosis is endemic in

Yellowstone National Park and likely spread from there out to all three states

[of Montana, Wyoming and Idaho].”

Despite the disease's persistence, she said, wildlife

management practices remain largely unchanged in affected areas, with the

exception of hazers — people on horseback or ATV who elicit movement of elk

herds off private property and away from cattle — deployed in Madison and

Paradise Valley to move elk away from private property with livestock.

According to FWP’s website, the agency, along with

informal input from the Elk

Management Guidelines in Areas with Brucellosis Working Group, annually

assemble a work

plan outlining potential management actions within the DSA or other areas

where brucellosis-exposed elk have been confirmed within the previous five

years. Before implementation, these management plans must receive formal

approval from the state Fish and Wildlife Commission.

Szymanski said she considers Montana’s program to

be successful at mitigating the spread of brucellosis. “We are very fortunate

to have the level of buy-in that we do, and a [cattle] industry that’s really

engaged in the discussion.”

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Mountain Journal is a nonprofit, public-interest journalism organization dedicated to covering the wildlife and wild lands of Greater Yellowstone. We take pride in our work, yet to keep bold, independent journalism free, we need your support. Please donate here. Thank you.

Related Stories

December 19, 2024

Bison Restoration in Greater Yellowstone gets $3M Boost

The Eastern Shoshone Tribe in Wyoming will

use the federal funding to expand bison habitat and research.

March 12, 2025

CWD Suspected in Dead Elk at Wyoming Feedground

As cases of the always-fatal

disease increase, wildlife managers are grappling with complex management decisions.

January 23, 2024

Call of the Mild

With

regional snowpack at record lows and average temperatures well above normal,

how are local wildlife coping with the unusual winter?