Back to StoriesCrazy Talk

March 27, 2025

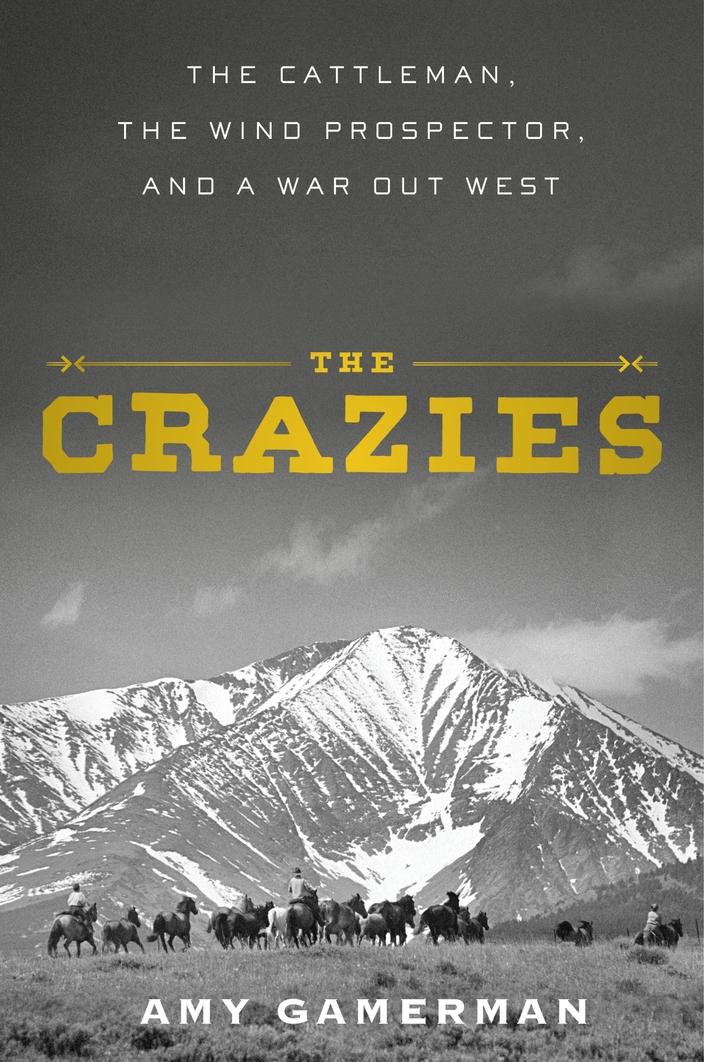

Crazy TalkIn new book on Crazy Mountain property battles, journalist Amy Gamerman explores the contrasting values altering ancient landscape

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article incorrectly referred to the East Crazy Inspiration Divide Land Exchange as including the Crazy Mountains and the Gallatin Range. It has been corrected to reflect that the swap included the Crazies and the Madison Range.

by Robert Chaney

The timeframe of the Crazy Mountains ranges from millions of years to handfuls of hours.

Trying to pack all that into a book left Amy Gamerman feeling as wind-tossed as the tumbleweeds blowing around Big Timber, where much of her new book, The Crazies, takes place. The Wall Street Journal reporter from Connecticut focused on a fight between a rancher developing a wind farm and a billionaire defending a trophy viewshed. It went to the printing press last summer, having to place bets on the climax endings of Montana’s most controversial climate-change trial and an equally contentious land swap linking luxury resorts in the Crazy and Madison mountain ranges. She chronicled the defeat of a windmill generation project just months before President Donald Trump would kneecap North America’s wind industry through executive order.

“You write up until the last minute you’ve got to let go of it,” Gamerman said shortly before beginning a tour of Montana bookstores in late March. “You try to make sure it’s updated. But at a certain point its pencil’s down. This won’t be the last word.”

What she did accomplish was a story encompassing the Paleocene volcanic eruptions that thrust the Crazy Mountains above surrounding seabed sediments to the revolutions in fracking and renewable power that underpin today’s energy economy.

“Everyone in this conflict thought they were doing the right thing, doing what was in the best interest of the Crazy Mountains,” Gamerman said. “It was Old West and New West — the transforming influence of big money into these traditional ranching communities. It was what it means to be wild and be wilderness and what that future should be. Plus renewable energy. And climate change was another story that happening in real time as I was reporting.”

The Crazies has a cast of characters longer and more colorful than the Yellowstone TV series, which Gamerman said she deliberately avoided watching to keep its soap operatics from staining her real-life melodrama. A 2017 Wall Street Journal assignment to profile Texas oil-shale billionaire Russell Gordy involved a visit to Gordy’s new ranch in the most scenic corner of the Crazy Mountains. In the process, she met Rick Jarrett, a cattle rancher tinkering with the idea of adding electricity-generating windmills to his struggling beef business.

“There were all these delicious ironies at work,” Gamerman said. “You’ve got a grizzled old rancher who doesn’t believe in climate change embracing renewable energy because the wind resource is a crop he can harvest. It’s something he can profit off of to continue a traditional way of life so he can keep running cows on a ranch that’s been in his family for five generations.

“On the opposite side is this Texas oil-and-gas billionaire who made a fortune fracking and drilling and leasing for an invasive form of coal mining in Illinois. He’s made his money defacing beautiful places and adding to greenhouse gasses, and now he’s draping himself in a mantle of environmental conservation and stewardship. He thinks there shouldn’t be wind turbines because they’re ugly.”

A third voice defining the landscape comes from the Apsáalooke Crow Tribe, who claim ancient ties to the Crazy Mountains. As Crow Tribal member and educator Shane Doyle put it, the Crazy Mountains “occupy a central place on the landscape — situated as an iconic lighthouse in a region of staggering vitality and contrast. They lie at the heart of Montana’s rich and treasured mosaic of culture and diversity, a heritage to celebrate, which dates back over 13,000 years and spawned one of humanity’s great achievements: Plains Sign Language.”

While reporting the book, Gamerman visited the archaeological site where the first evidence of Clovis people was unearthed. It was a child’s tomb, filled with spearpoints and other Paleo-Indian tools in various stages of completion: “an instruction manual with an ancient culture’s most vital information, written in stone,” she wrote.

“I stood on that spot, looking east at the Crazy Mountains,” Gamerman said. “The sun would come up over the mountains, and this would be the first thing touched by the sun as it was rising. You feel this tiny spark of connection to what these people must have seen and thought 13,000 years ago.”

The mountains invite imagination. Elise Atchison fictionalized the economic battles over the landscape in her 2022 novel Crazy Mountain. The Philip Morris tobacco corporation built a luxury resort modeled after a Wild West town that became known as the Marlboro Ranch in 2000.

That in turn got tangled in a growing clash between wealthy newcomers seeking splendid isolation, long-time farmers and ranchers accustomed to being left alone, and hunters and hikers determined to keep their access to popular big-game and wilderness public acres.

The East Crazy Inspiration Divide Land Exchange proposal taxed the public attention span for years. Initially considered as a way to settle long-standing fights over private ranches encroaching on public access, it expanded into a complex trade of thousands of acres in both the Crazies and the Madison Range adjacent to the ultra-luxury Yellowstone Club’s expanding resort.

In January, the Custer Gallatin National Forest authorized swapping 3,855 acres of public land in the Crazy Mountains and Madison Range for 6,110 acres of private land in both landscapes. Much of the bargain depended on consolidating the “checkerboard” ownership mix of public and private land that had bedeviled Montanans for generations. But while the checkerboard layout arbitrarily gave all players bits of high- and low-quality landscape, the swap raised questions of relative value in viewsheds, wildlife habitat, scenic trails, Indigenous culture and real estate potential.

In January, Yellowstone Club representative Mike DuCuennois told Montana Free Press the exchange was “a huge step forward to secure permanent public access and further consolidate public lands in the Crazy Mountains,” a likely reference to a smaller swap the Forest Service authorized in 2021.

Other observers were less optimistic.

“I share an uneasiness felt by many who have taken the time to dig in,” David Tucker wrote in Mountain Journal a year ago. “It feels like the public is getting a raw deal and that a precedent is being set for future land disputes.”

The Crazies has a cast of characters longer and more colorful than the Yellowstone TV series, which Gamerman said she deliberately avoided watching to keep its soap operatics from staining her real-life melodrama.

For Gamerman, the tableau illustrated changes that roil American society across its urban/rural and rich/poor fault lines.

“It’s interesting how differently each person can see what’s in front of them and how the landscape means different things for different people,” she said. “There are billionaire trophy ranchers creating their own private national parks. They’re seeing extraordinarily valuable irreplaceable, precious things where once it’s gone, you can never obtain it again.. With these guys, it’s almost more about curating than conserving: ‘This is my rare collection of beautiful land — I’m protecting it and its value like an artwork.’

“For a generational rancher like Rick Jarrett, it’s a struggle to hang on to a dwindling ranch that’s gotten smaller with each generation … This is land his ancestors suffered extraordinary amounts of punishment to hang on to, and resources he should be able to exploit. He looks at those snowy mountains and wonders ‘is there enough snowpack to irrigate my alfalfa fields and support my cows?’ He loves it as much but in a different way.”

The courtroom struggle between Jarrett and Gordy confounded many taken-for-granted political assumptions. For example, while practically all the people Gamerman interviewed would consider themselves conservative Republicans, many were deeply invested in the same wind energy that Trump said “may lead to grave harm — including negative impacts on navigational safety interests, transportation interests, national security interests, commercial interests, and marine mammals.” Meanwhile, others whose fortunes depend on exploitation of private property rights used legal arguments about “aesthetic value” and “natural beauty” to block a fellow property owner from developing their own resources.

"The newcomers don’t know their neighbors. And as they’re dying off, the people who own the big ranch up in the mountains aren’t showing up at the funeral with a casserole.” – Amy Gamerman, journalist, author, The Crazies

The results have transformed the communities around the Crazy Mountains. Many of the newcomers buying up its scenic vistas have maintained the agricultural traditions.

“When you are looking at these owners of large ranches, they say they’re still supporting the local economy, hiring ranch hands, raising cows,” Gamerman said. “Maybe not as many, but they’re supporting a way of life.

“But it’s a very selective way of contributing to the community. What I found in the case of Big Timber, was the presence of so many really wealthy landowners, the rise of these mega-ranches, with billionaires buying up dozens of small family ranches, putting them all together — it’s like scooping out a community from the inside. The newcomers don’t know their neighbors. And as they’re dying off, the people who own the big ranch up in the mountains aren’t showing up at the funeral with a casserole.”

That has implications for American society at large, Gamerman added. Few big-city people have any understanding of the grinding amount of work that goes into a cow-calf operation, how a rancher’s retirement plan depends on their children’s ability — and willingness — to buy out their parents, how drought and wildfire and shorter winters all chip away at the value of turning a bull into a burger.

“There’s a profound lack of sympathy for that on the East Coast,” she said. “And I don’t think folks in Big Timber were predisposed to think warmly about somebody from the East Coast either. But look at what’s going on in Montana. Look at the rise of American oligarchy. If you want to see the implications of that, consequences of that, what that looks like in real time — go look at Montana.”

Book tour dates

Wall Street Journal reporter Amy Gamerman will give five public readings from her book The Crazies in March and April across Montana. Events include:

March 31, 7 p.m., Ravalli County Museum, Hamilton

April 1, 7 p.m., Fact and Fiction Bookstore, Missoula

April 2, 6:30 p.m., Montana Book Company, Helena

April 3, 6 p.m., Country Bookshelf, Bozeman

April 4, 6 p.m., Carnegie Public Library, Big Timber

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Mountain Journal is a nonprofit, public-interest journalism organization dedicated to covering the wildlife and wild lands of Greater Yellowstone. We take pride in our work, yet to keep bold, independent journalism free, we need your support. Please donate here. Thank you.