Back to Stories

MOUNTAIN JOURNAL: How and when did the power of photography first register with you?

JOHNS: I would not say I feel daunted by my father or his positions. I have a huge amount of respect for him and the people he interacts with. I hold a high standard of excellence for myself and I tend to be pretty hard on myself. But as I grow, I try my best to soak up and channel his wisdom. I realize that the very qualities that have made him such a great dad — his patience, passion, kindness and willingness to let people find their own vision without interference — are the qualities that have given him great success and inspired tremendous devotion from the people with whom he works. He leads by example, and together with my mother they have always insisted that we (my siblings and I) stay true to who we are. If I felt daunted by anything it would be the rapidly changing, fast moving and increasingly subject to debate world of the media. Sometimes I feel like I can’t keep up.

MOJO: What' the best advice you've ever received and who gave it to you?

May 2, 2018

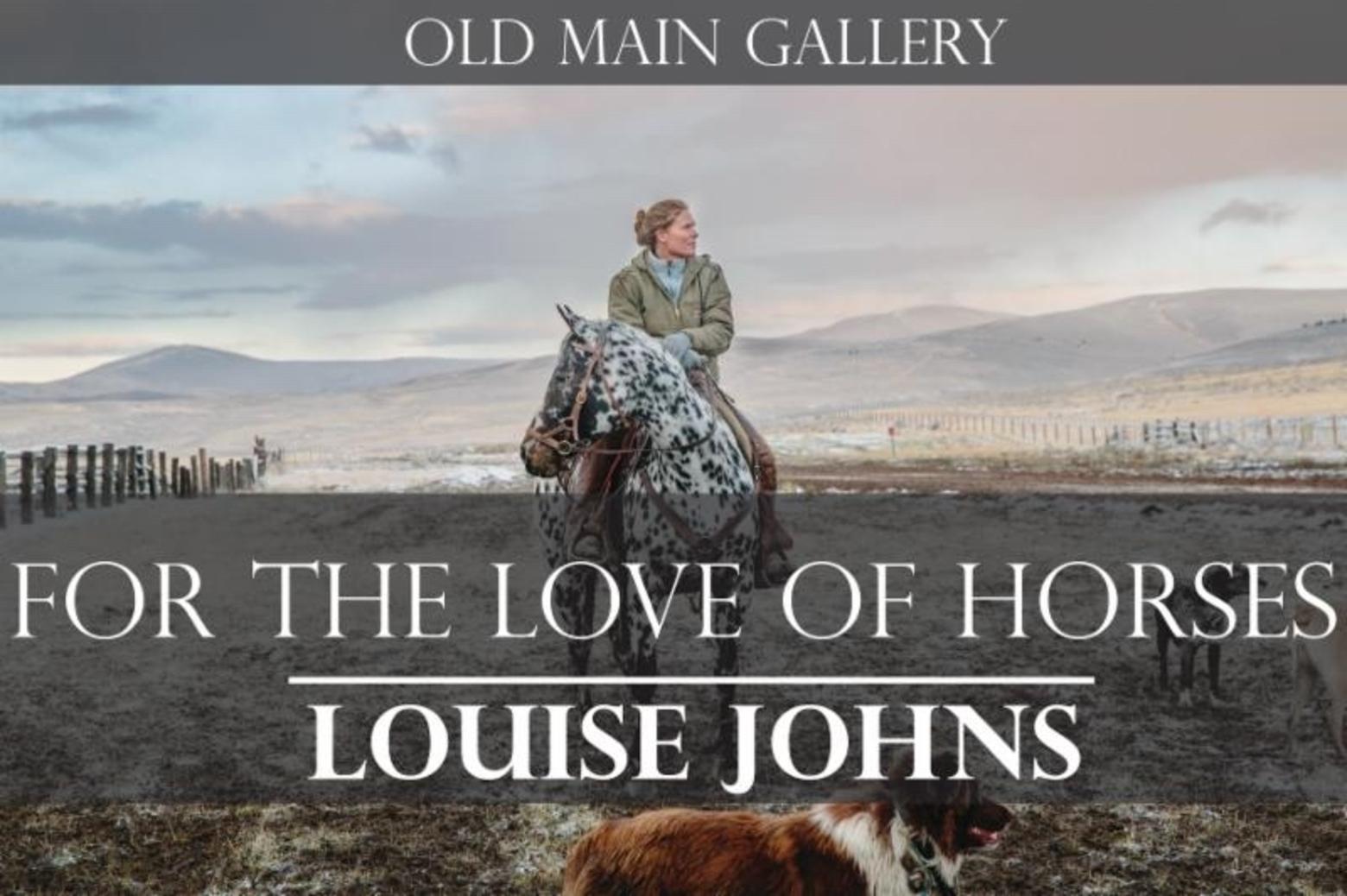

Together We Go: The Ways Of Horses And Western Women

Photojournalist Louise Johns explores the special bond that defines our region

Meet Louise Johns. She is living her dream as an emerging photographer and she is a member of the young generation worth watching. Louise will be putting together photo essays on the relationship between Western women and their horses, but it is really an exploration of the convergence of humans, animals, topography and ways of life.

Born and raised in rural Virginia, Louise was raised a competitive horseback rider in a sport called Three-Day Eventing. Upon graduation from high school, she came west to the University of Montana for college, a move enthusiastically embraced by her parents who also have become transplanted in the northern Rockies. Louise’s father, Chris, is a longtime photographer for National Geographic, who rose to the position of editor in chief of the magazine and recently served as a catalyst for NatGeo’s May 2016 edition devoted entirely to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and the story told by Bozeman’s David Quammen.

After studying photojournalism in college, she has been a photographer’s assistant, freelance shooter and National Geographic Young Explorer. Louise had the closing photograph in that issue and once, you see it you won’t forget it. Check out information on Louise's solo show opening at Old Main Gallery in Bozeman on Friday, May 4. If you're in the area, stop in and see her work.

Not long ago, we had a conversation with Louise.

MOUNTAIN JOURNAL: How and when did the power of photography first register with you?

LOUISE JOHNS: I had the great privilege of traveling with my dad during some of his assignments as a photographer for National Geographic Magazine. When I was about 10 years old he took me with him for a story he was photographing about Sacagawea. We drove from our home in Virginia to Montana’s Pryor Mountains, and camped there for a week where he and his assistant, Bobby Model, were photographing wild horses as part of the story.

One day, we had been out since dawn looking for horses and my dad had finally scoped out a spot and set up a camera on a tripod. I was wandering around watching the horses. I was a very quiet and shy little girl, but I was curious. I went over to his camera and started looking through the lens, clicking the shutter, watching the horses move in and out of the frame. Slowly the mood changed, and I ended up shooting pictures for about an hour, surrounded by the usually flighty, skittish horses. During that time, my dad never said a word. He never coached, advised or stopped me from what I was doing. He just let me discover. That was the first time I really looked through a camera, but it wasn’t until years later that I picked up a camera again, and realized that moment had really resonated with me. The camera was a way to record the beauty of life and be a still, quiet witness. I could follow my curiosity and communicate what I saw and felt through the camera.

About 10 years later I took a photojournalism class at University of Montana, and that’s when I first considered that I might want to make a life as a photographer. The more I photographed, the more I understood what I had always heard the great photographers say: that photography is an act that comes from the heart. From the beginning, I’ve had some of the best mentors in the world that really instilled in me the values of photojournalism. So I figured that if my heart was in it, I could learn to use my camera, develop my eye and find my way.

MOJO: Given your father's skill, the positions he's held and the people with whom he's interacted, do you feel daunted?

JOHNS: I would not say I feel daunted by my father or his positions. I have a huge amount of respect for him and the people he interacts with. I hold a high standard of excellence for myself and I tend to be pretty hard on myself. But as I grow, I try my best to soak up and channel his wisdom. I realize that the very qualities that have made him such a great dad — his patience, passion, kindness and willingness to let people find their own vision without interference — are the qualities that have given him great success and inspired tremendous devotion from the people with whom he works. He leads by example, and together with my mother they have always insisted that we (my siblings and I) stay true to who we are. If I felt daunted by anything it would be the rapidly changing, fast moving and increasingly subject to debate world of the media. Sometimes I feel like I can’t keep up.

"Develop your voice so you can thoughtfully amplify the voices of others. Understand who you are and constantly refine your vision. Be grounded, and continually hone your voice throughout your life by learning and growing with an open mind and an open heart." —Louise Johns

MOJO: To some people, the informed, photography can be like painting. Those who do it well understand the subtleties of what makes for a great photograph (or poem). Describe the challenge of making an image that is really saying something.

JOHNS: I think master photographer Cartier-Bresson says it best: “It is putting one’s head, one’s eye, and one’s heart on the same axis.”

In my experience the challenge of making an image that is really saying something comes with the ability to be present and live in the moment, so you can see, feel and experience the world around you. You’re looking for moments. And you have to then know your camera well enough to be able to record and creatively translate the moment in the blink of an eye. I came to love photography because I found it as a means to communicate the things I care about — the precious, subtle moments of life, the moments that reveal the core of who we are. Making a great image has a lot to do with the time spent when you’re not photographing — listening, learning, asking questions and nurturing relationships. I’ve been taught since the very beginning that in order to tell a great story you must live it. Another integral part of the process is having a really good photo editor. An editor will help you really see your pictures and piece them together in a way that communicates to a broader, diverse audience. A good editor will play into a photographer’s strengths, help them grow and find their voice.

MOJO: Your image at the end of the May 2016 Nat Geo focused on Yellowstone brought a resonant conclusion to the issue. Tell us what's going on there and why it succeeds with a kind open-ended narrative?

JOHNS: Truth is I didn’t even realize the significance of this image until NGM photo editor, Kathy Moran picked it out. Sometimes it’s hard to step back and detach yourself from your work, especially when it is so close to your heart and you believe so deeply in the people and places it represents. This image was about 2 years in the making. It began in 2013 when I worked as a horse wrangler at the J Bar L Ranch in the Centennial Valley of Montana. That’s where I got to know Elle Anderson, the little girl in this picture, and it was my first real glimpse into a rural western way of life, and I was a part of that life. Living with that community had a huge impact on me, and the relationships I made there have stuck with me and lead me to other places. I made this image of Elle in 2015 when I was watching the children for their mother, Hilary. I have always loved spending time with the children, going on little adventures with them and entering their world in this boundless landscape. I think it succeeds as a final image for the Magazine because it speaks to the future, the purity of a young soul and the very essence of living in wide open spaces.

MOJO: You are drawn to rural Western people. And your work in the months ahead for MoJo will explore the connections women have to horses. What intrigues you about these subjects?

JOHNS: My horses have taught me the most important lessons in life — commitment, persistence, compassion, patience, kindness, and that i have a responsibility to care for something that is far bigger than myself.

When I moved to Montana I learned about a different kind of horsemanship— one where horses are integral to working on the land. They are in many cases a key component of rural western life, and have been for a long time. What I knew of horses took on a whole new meaning that I’m continually discovering through my work in the rural west. I want to explore stories of other women who have been shaped by horses, what those relationships are like. We can learn a lot about life through our horses, and I think they have a way of cutting to the core of who people really are. Collectively I think the voices of these women will reveal a depth to the human soul which is often missed in our daily lives. I believe horses have the power to bind people, and to help us all remember what is most important in life.

MOJO: What' the best advice you've ever received and who gave it to you?

JOHNS: Develop your voice so you can thoughtfully amplify the voices of others. Understand who you are and constantly refine your vision. Be grounded, and continually hone your voice throughout your life by learning and growing with an open mind and an open heart.

This is collective advice that’s been given to me by some wonderful, wise mentors, namely my mother and father, my partner Daniel Anderson, Susan Welchman, Nick Nichols, Joe Riis and Erika Larsen.