Back to StoriesThe Healing Nature of Nature Therapy

May 8, 2024

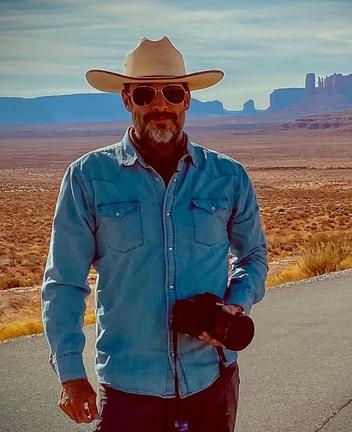

The Healing Nature of Nature TherapyIn a world stuffed with technology and distraction, Bradley Orsted reaches out to touch the natural world in Greater Yellowstone

Story and

photos by Bradley Orsted

The

wildness of Greater Yellowstone inspires wonder and awe in everyone willing to

venture out and touch it, walk in it, observe its wildlife, and breathe in its

air. We are beginning to understand time in nature also has a curative effect

on everything from PTSD, depression, anxiety and substance abuse, to lowering

cortisol levels. Many therapists have begun seeing their clients in the woods

in lieu of a stuffy office, using the backdrop as an integral part of the

treatment. But what exactly is nature therapy, how does it work, and how can we

self-medicate?

For me, nature therapy is any time I spend out of doors where my central

nervous system settles down. It’s really that simple. Any place I can stroll or

sit long enough for the birds to go back to what they were doing will suffice. With

some patience and practice, this can be achieved almost anywhere: a city park

has the same restorative benefits as an alpine lake. Sound crazy? Science is

finally catching up with what poets and indigenous cultures have known all

along: Nature heals. Mindful time in the outdoors unlocks the medicine already

hard-wired within all of us. But how?

When I enter the nature headspace, especially in grizzly country, I become a heightened sense of awareness. My elevated consciousness stimulates a feeling of connection and interrelationship with the world around me.

Pick a

religion. Go ahead, any religion. I’ll bet there is a prophet or disciple who was

either sent, or willingly sought out the wilderness for wisdom and healing.

From desert hermits to the ascetics, human beings have been venturing into

nature to navigate the wilderness both underfoot and within since the dawn of

time. Black Elk, the well-known holy man of the Oglala Lakota went to the Black

Hills to seek his visions, Muhammed received his divine message in a cave,

while the Buddha sat under the Bodhi tree. Both Jesus and Moses went to the

wilderness. Christ spent his 40 days wandering in the desert while Moses got 40

years; nepotism on an Old Testament scale. The point is, if we’ve sought wisdom

and healing in nature for 99.9 percent of our time as a species on this planet,

why are we now turning to the not-so-great indoors for healing?

Our brains

and physiology evolved in nature, in the great out of doors. Mountain meadows,

trees, water, fire, wind and skies. We are all biophilic. As the

environmentalist-poet Gary Snyder says, “Nature is not a place we visit. It is

home.” It’s where we developed as a species, and what we know at our collective

core. We did not evolve in these boxes within boxes inside boxes we call homes that

are artificially heated or cooled to match our ever-present whims, and where we

self-lambaste with technology, constantly overstimulated, but never really

getting anywhere. We need sunlight and fresh air more than ever to keep us

balanced.

Even animals

seem to seek nature therapy. I know it sounds odd, and it may just be a

longshot, but here’s what I’ve seen: When animals are wounded or sick, they

seek draws, ravines or thickets to lie down in while trying to hide, rest and

heal. Bears dig roots for their medicinal values. Nature is their pharmacy. I’ve

also witnessed both bison and bears appear to enjoy the views in Yellowstone National

Park, while pausing to acknowledge it. Passive awe. It’s one of the key

components to a healthy lifestyle.

When I

enter the nature headspace, especially in grizzly country, I become a

heightened sense of awareness. My elevated consciousness stimulates a feeling

of connection and interrelationship with the world around me. My internal

dialogue slows. My mind turns to beauty and introspection. I remind myself it’s

good to be a little cold, picking up the pace on the trail. In nature, I’m

sometimes overcome with such a sense of tranquility and compassion that my body

seems to transcend the corporeal world. My central nervous system begins

quieting because I am home, and this is recognizable to my being. The reason

this is happening is easily explained in the brain.

When we

experience nature, even on a superficial level, we’re triggering our bodies to

release “happy hormones.” These four feel-good hormones are dopamine, serotonin,

endorphins and oxytocin. As neurotransmitters, they are naturally released

inside our brains when we merely spend time outside. Simultaneously, we’re

lowering blood pressure and allowing our brains to take a much-needed break

from the barrage of a multitude of mostly meaningless decisions we make every

day.

Five hours a month is the recommended amount of time we need outside to

boost our immunity, elevate creativity, and help settle the central nervous

system, aka homeostasis. That’s only 10 minutes per day outside walking, or

even just sitting in the sunshine, to reap the restorative rewards of Mother Nature.

Fold in a digital detox as well during those 10 minutes a day outside and watch

your focus return. Don’t believe me? Try it for a week.

We did not evolve in these boxes within boxes inside boxes we call homes ... We need sunlight and fresh air more than ever to keep us balanced.

Writing

this in the shadow of the Crazy Mountains in south-central Montana, I’m

fortunate to have a 360-degree view of wilderness around me. However, I also

spend a lot of time at a city park next to the wastewater treatment facility

that parallels a busy set of train tracks. When the wind blows just right off

the Crazies and across the pungent retaining pool, and as a nearby BNSF train barrels

for Billings, I can still smile and feel the energy coming off the earth.

It doesn’t

sound like the perfect setting for nature therapy. That’s why I enjoy it so much.

Having spent enough time in the wild, I can now access that mindfulness

wherever I am. It doesn’t matter if it’s downwind of a retaining pond next to a

speeding locomotive, or navigating a busy city sidewalk. I can breathe deeply,

control my anxiety, and lean into the calm knowing I’m home.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Mountain Journal is the only nonprofit, public-interest journalism organization of its kind dedicated to covering the wildlife and wild lands of Greater Yellowstone. We take pride in our work, yet to keep bold, independent journalism free, we need your support. Please donate here. Thank you.

Related Stories

January 21, 2025

Why ‘Yellowstone’ Became a Dirty Word to so Many Montanans

No one ever claimed the hit cowboy soap opera was aiming for realism. But for Montana locals, the show’s many day-to-day...

November 22, 2023

The Arrival of Harriman’s Iconic Trumpeter Swans

By the early 1900’s trumpeter swans were nearly extinct, but concerted efforts have reinvigorated their numbers. Land around Harriman Ranch State...

July 11, 2024

Counting Cougars

In this guest essay, photographer and Yellowstone guide MacNeil Lyons recounts the top 10 most thrilling mountain lion sightings he's experienced....