Back to StoriesIs 'Wildland Conservation' That Does Not Emphasize Wildlife Really Conservation?

April 28, 2021

Is 'Wildland Conservation' That Does Not Emphasize Wildlife Really Conservation?Delightful new 'Artist's Field Guide To Yellowstone' offers inspiring reasons to care about protecting wildlife in Lower 48's famous bioregion

by Todd Wilkinson

For nearly 35 years I’ve been writing about “wildlife art”—not paintings and sculpture created by animals, of course, but by artists who choose to depict wild, not-human creatures as subject matter. While no artist is obligated to be an advocate for protecting the things that earn them money and professional standing, it’s always amazing how reticent some artists are to take a stand for the environment.

EDITOR'S NOTE: A portion of book proceeds will be donated in support of Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative which uses science to help humans and wildlife better coexist in healthy ecosystems. You can purchase the book at tupress.org using promo code NRCC at checkout.

There likely would be no Yellowstone as we know it today had it not been for the surreal depictions of the landscape that became the park by Thomas Moran and the early nature photography of William Henry Jackson. The movement to save bison from extinction might have happened too late were it not for romantic painters who called attention to the slaughter. There would probably be millions fewer waterfowl and other species that depend on wetlands for their survival without the advent of decorative Duck Stamp licenses that generate revenue for safeguarding habitat.

Is wildland conservation that does not prominently emphasize wildlife really conservation?

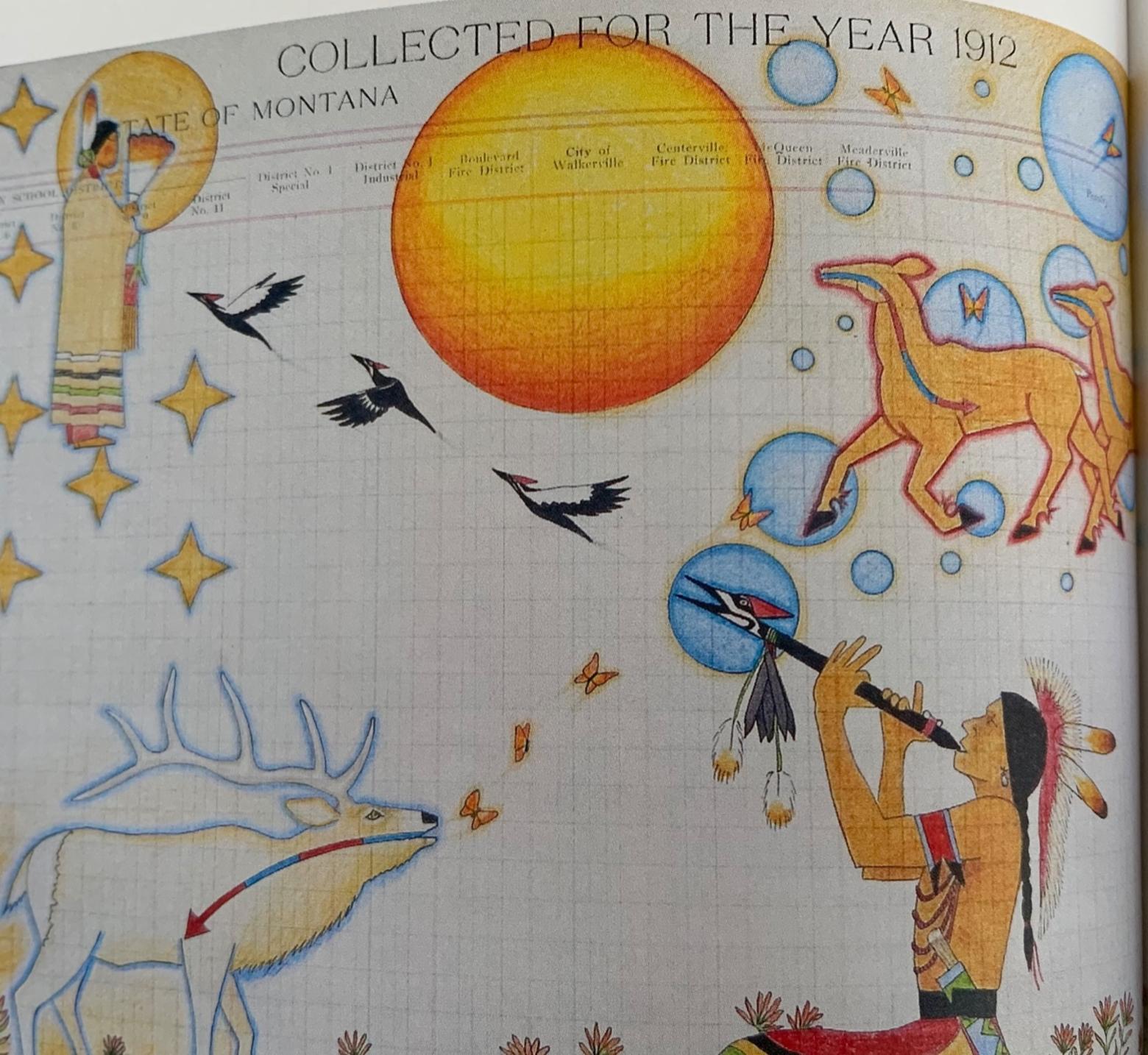

The iconography of wildlife is powerful and it arouses something deep in the primitive parts of our brain, stimulating likely the same kind of archetypal imagery known to paleo-humans and their predecessors hundreds of thousands of years earlier. The point is wildlife in art attracts attention, it can deliver people to places without them having to actually go there, it can educate and when we are enlightened we are more likely to care.

None of this has been lost on Katie Shepherd Christiansen who has with admirable persistence moved forward a book project that celebrates critters and other life forms in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the richest bioregion holding large terrestrial wildlife remaining in the Lower 48 states.

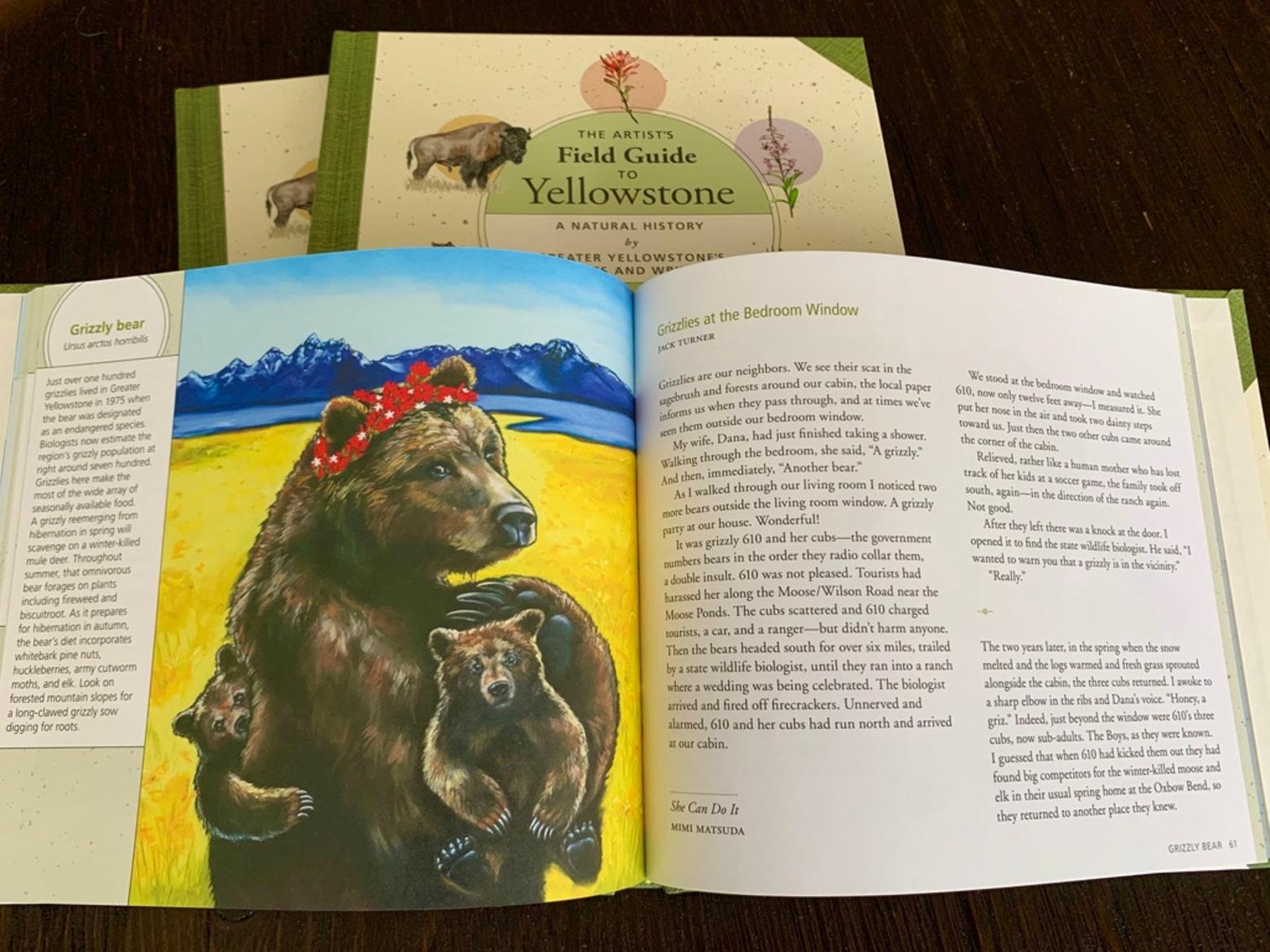

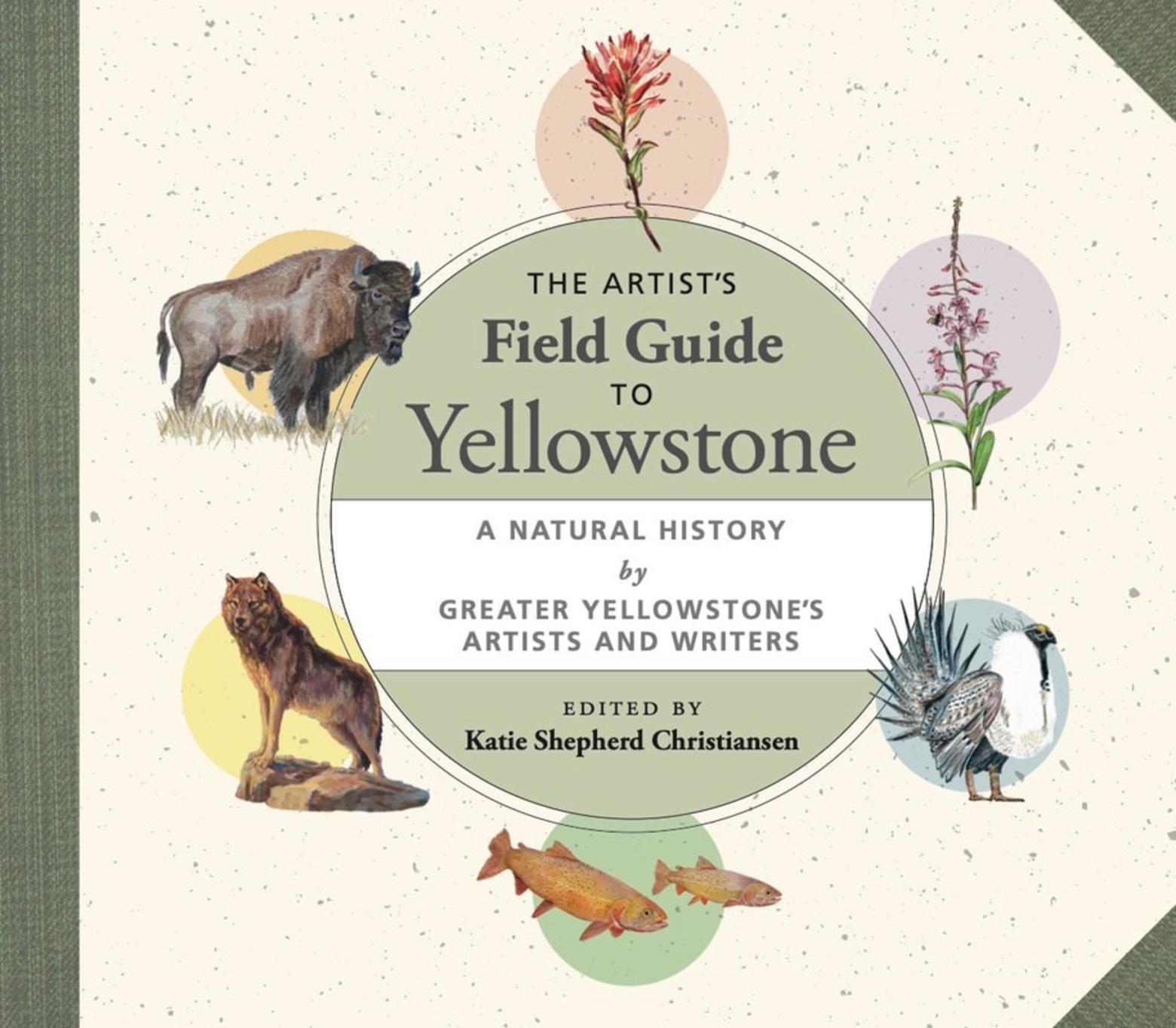

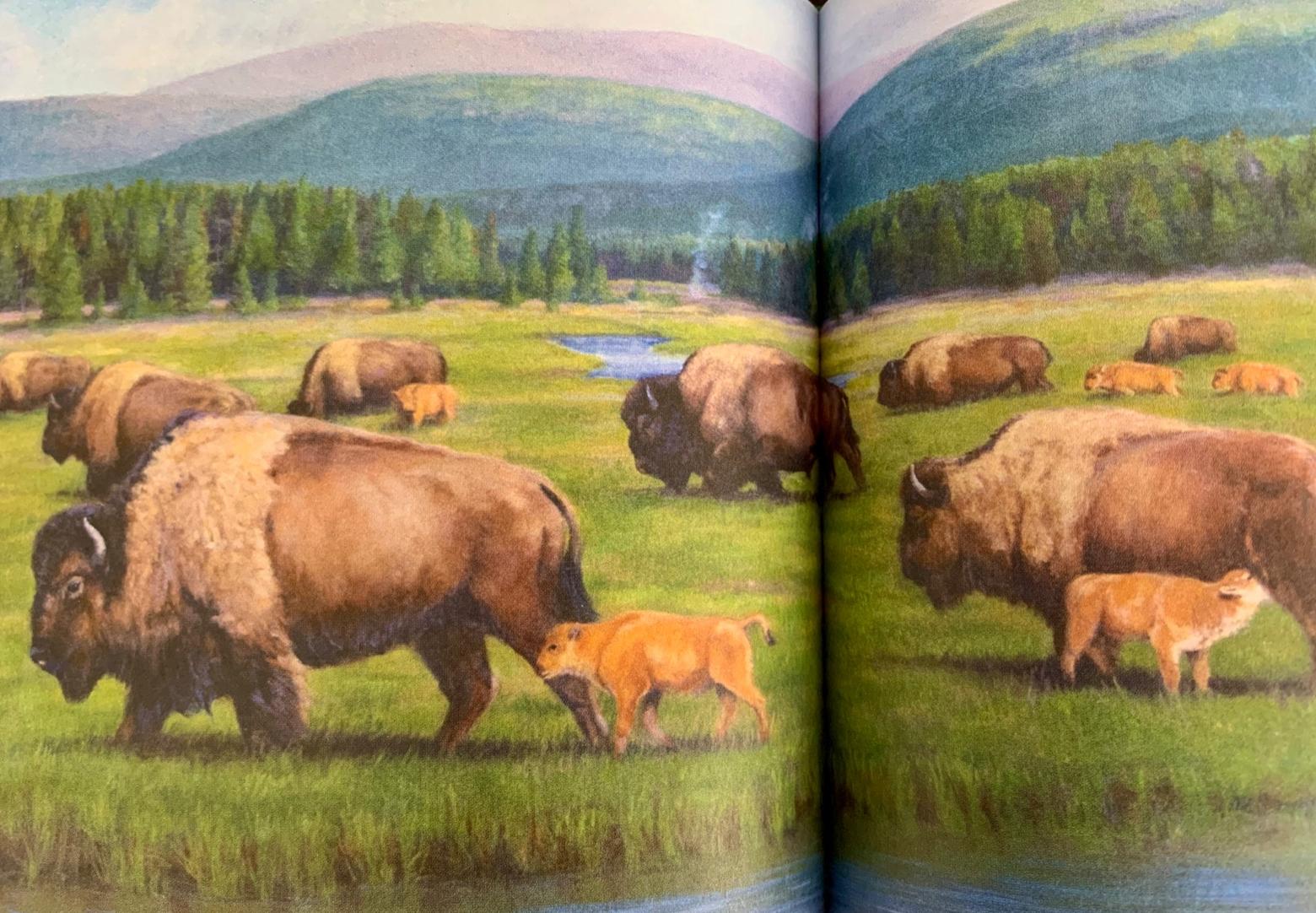

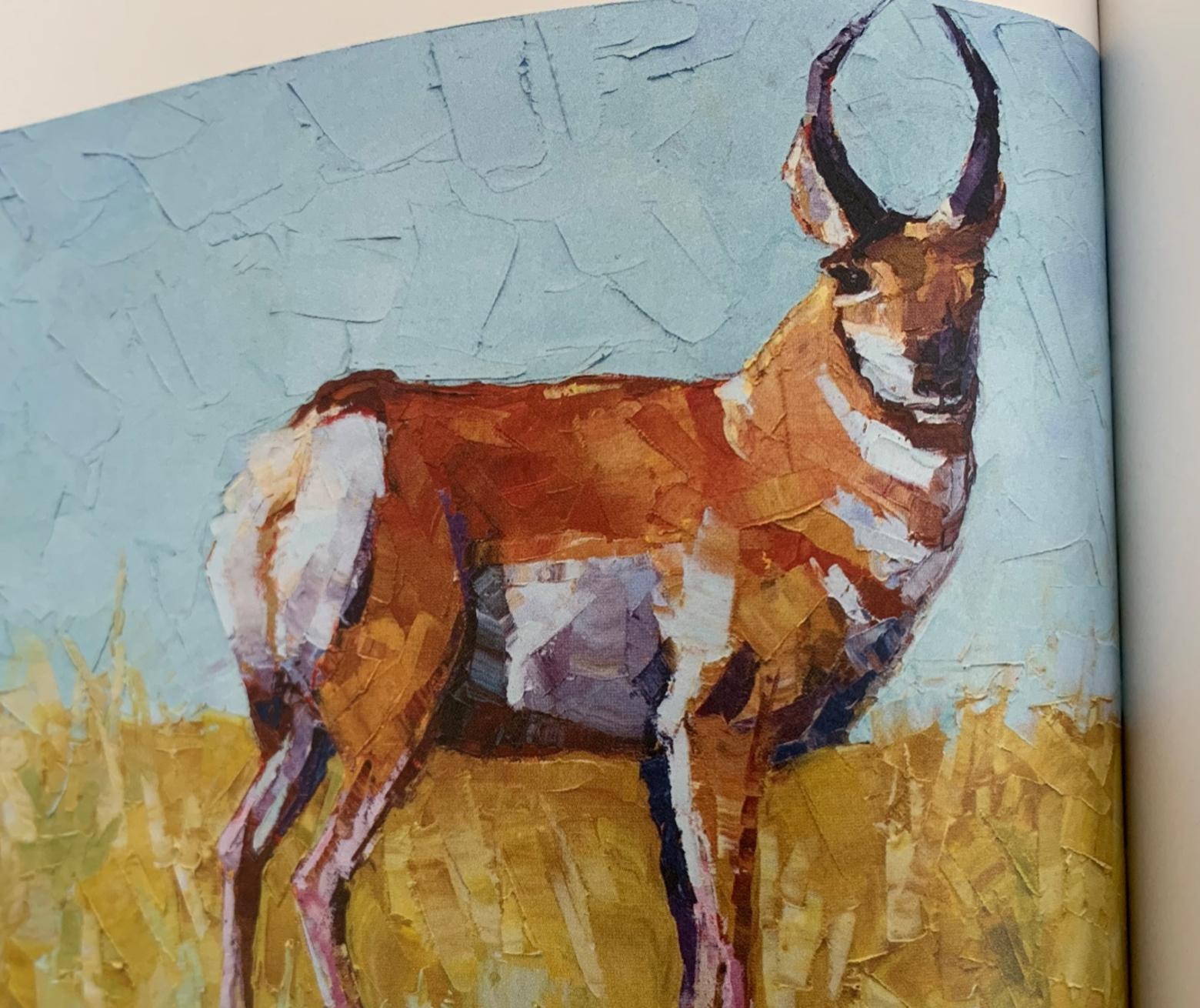

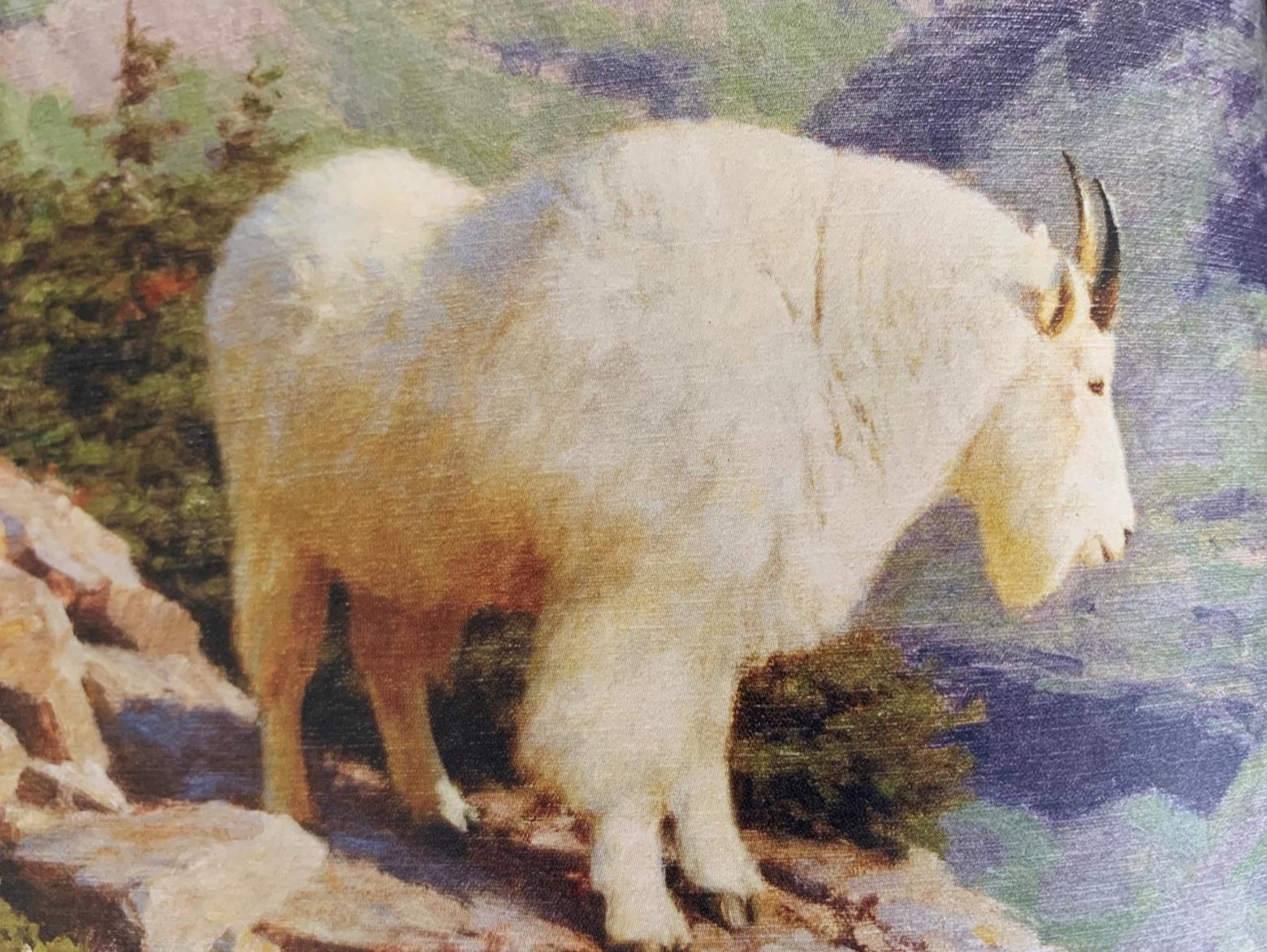

The delightful new volume The Artist’s Guide to Yellowstone: A Natural History by Greater Yellowstone’s Artist and Writers (Trinity University Press) is Christiansen’s brainchild. Now it is out and well worth the wait. Brilliantly, stellar artists are matched with writers and together they focus on celebrating an individual animal that roams Greater Yellowstone's wild country.

The visual artists include Kalon Baughan, Tamara Callens, Meredith Campbell, Sue Cedarholm, Derek DeYoung, Loretta Domaszewski Katy Ann Fox, Dave Hall, Dwayne Harty, DG House, Will Hunter, Sarah Kariko, Laney, Jenni Lowe-Anker, Mimi Matsuda, James Prosek, Robert Schlenker, Jocelyn Slack, Tucker Smith, Kay Stratman, Kara Tripp, Shannon Troxler, Kathryn Turner, John Wasson, Carrie Wild, and Monte Yellow Bird Sr.

The roster of writers, hailing from across the ecosystem, includ Elise Atchison, Rick Bass, Todd Burritt, Tom Campbell, Katie Christiansen, Lyn Dalebout, Matt Daly, Joanne Dornan, Gary Ferguson, Matt Hart, Geneen Marie Haugen, Susan Marsh, Craig Mathews, Arthur Middleton, Doug Peacock, Karen Reinhart, Kelsey K. Sather, Jack Turner, Rebecca Watters, Tina Welling, Marylee White, Connie Wieneke, Todd Wilkinson, and Terry Tempest Williams.

Christiansen is an artist, writer, conservationist, avid outdoor recreationist and mother. She lived in Greater Yellowstone for most of the last decade between Bozeman and Jackson, though she is currently based in Boulder, Colorado.

“I have worked for environmental NGOs for most of my career, spanning science, policy, management, education, outreach, and the arts. Through my organization, Coyote Art & Ecology, I have collaborated with such groups as the Trust for Public Land, National Geographic, the WILD Foundation, Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics, and AMB West Ranches,” she says.

Holding a Masters Degree from the Yale School of the Environment, where she co-taught Yale undergrad courses organized around Yellowstone and Global Change, Chrisiansen traveled with student groups to guide them in exploration and study of the biological, social, and policy contexts of the region.

Not long ago, Mountain Journal caught up with Christiansen and engaged her in an interview.

MOUNTAIN JOURNAL: What was the genesis of this project? There are a lot of different books out there about Yellowstone/Greater Yellowstone, but this one is certainly novel and that's saying something.

KATIE SHEPHERD CHRISTIANSEN: The concept of the book is this unusually integrated, layered project that weaves together science and art as communicated by fifty storytellers, and organized like a traditional field guide. By science I mean what we think of as traditional natural history knowledge and illustration, as well as what is known by scientific study and investigation about the state of wildlife. This scientific knowledge is shared beside and through the book’s art, which ranges from modern folk style to fine western artwork, as well as reflective, diverse prose and poetry, all created by expert storytellers from the local community.

Taken together, it sets out to tell a story of Yellowstone across different mediums, and from the fifty unique perspectives held by each contributing artist and writer. The perspectives of each contributor are accounting for the human struggle to interact with our landscape here: what does it mean to live on land shared with grizzly bear and bison? What does it look and feel like to respect and give deference to the wild here? What does it mean to see one’s self intricately tied to Yellowstone’s community of life, and what are the implications for how we go about existing as humans in this shared space?

MOJO: Part of those questions above relate to advancing ecological literacy, which is a central focus of MoJo, your organization Coyote Art & Ecology, and the Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative which is receiving proceeds from book sale. How does this project, which brings together artists with other professionals address the questions you raise above?

CHRISTIANSEN: Admittedly, when I came to the idea for the project, I didn’t fully understand how such a creation could fit into the larger conservation effort. I started the project interested in creating a unique kind of field guide that might be of interest to a different readership, thinking linearly that education about natural history equates to support for conservation. The other initial inspiration was wanting to bring together and empower a community of people: the artists and writers who contributed to this project. And while these were not bad thoughts, they were missing the substance as to how and why such an integrated community effort holds certain potential to affect change through values and stories.

So I like to think of this book as having two origins -- the first when I envisioned an artful take on a natural history field guide, and the second when shifts in my perspective provided a better understanding of the task we are up against. I believe I then saw the true potential of this project and how I could better integrate content and offer the community a more powerful testament to our values.

MOJO: As you reflect back on the connection between art and conservation and its importance, what comes to mind?

Good and proper conservation is often understood as science-driven decision making. And to some extent, this is true: we should be looking to the best available scientific understanding of a subject, such as wildlife populations or shifts in habitat suitability, when considering how we are to respond to a particular issue. However, it is simply not possible that decisions only be based on “what the science tells us.” Decision-makers are tasked with interpreting “the science” into policy or management, and decision-makers, like the rest of us, are by nature of being human, biased. This bias isn’t necessarily out of ill-intent or used for manipulation, rather it simply arises out of one’s experiences and perspectives. It is the lens through which we all see the world.

Conservation, then, is a values and perspectives aligning task. It is a process of integrating scientific understanding with our knowledge of social context, policy process, and goals, and all backdropped by the integrator’s standpoint.

MOJO: You’ve designed some of the signage used at Story Mill Park in Bozeman and Astoria Park Conservancy in Jackson Hole—two places where people move into places inhabited by wildlife.

CHRISTIANSEN: Art is in the business of presenting ideas and perspectives that inspire the formation of values. It is a mechanism, as is science, for making sense of the world around us. But unlike the way we label science today, art freely admits to its bias and in so doing provides a space for all of us to consider how our own standpoints influence the way we see the world and understand ourselves. It reminds us that we form our values through the narratives with which we identify. And that we can choose different stories that will lead us to different values.

Why does any of this matter? Because today’s predominant values-driving stories are not going to be sufficient for creating and maintaining a sustainable future both here in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and at a global scale. Art that conveys the beauty of the natural world, and our awe in and responsibility to it, can serve as a foundation for building values around ecologically rich systems that support human life.

"To the people of Yellowstone: may this book deepen our understanding of the wild community we make home. And to those who might never experience a grizzly at your doorstep, the heralding song of a western meadowlark, or the dancing of aspens in the fall: may you experience this place through our stories and art." —Katie Shepherd Christiansen

MOJO: What did you learn and come to appreciate more in putting this book together.

CHRISTIANSEN: The experience of building a project like this--and engaging contributors, project partners, donors, and media--has proved to be an attempt to build something that doesn’t fit within the existing social structure. This project, like many others, has had to rely on various traditionally closed or conventional systems and institutions in order for it to become reality: systems and institutions like book publishing, philanthropy, conservation, and even the art community.

So it’s provided an opportunity to see where within society and our social systems we are willing to give room for new ideas, as well as where systems and institutions are less likely to create such space. I’ve also come to appreciate the depth of commitment that local storytellers maintain for Yellowstone’s wildness. The artwork and stories in this book are heartfelt and emotional. They are each testaments to what we must fight for here. They are a chorus of calls for us to see with new eyes the wild before us, and to not squander our riches.

MOJO: You’ve said that art should be recognized as more powerful ally of conservation.

CHRISTIANSEN: For the group of artists and writers who contributed to this compilation, this book was but a small outlet when considered against all they do to offer their expertise on behalf of wild places. The conservation community is missing a major opportunity by siloing “art” as something whose place is exclusively on gallery walls. Conservationists should be partnering with artists at every opportunity to make us all more effective at presenting a compelling narrative for nature. And conservationists owe the art community an overdue thanks for their contributions that go unrecognized as “conservation work” and yet lay the values framework within communities and minds that leads to conservation-mindedness in our community.

MOJO: What do you hope it accomplishes?

I conclude my preface with this: “To the people of Yellowstone: may this book deepen our understanding of the wild community we make home. And to those who might never experience a grizzly at your doorstep, the heralding song of a western meadowlark, or the dancing of aspens in the fall: may you experience this place through our stories and art. Let this book be an invitation to know your own wild community in your own wild corner of the world.”

And that really is my hope, that this project might inspire an updated understanding of nature and of ourselves as we attempt to live on this landscape that we share with wild neighbors. If we’re willing to be vulnerable to this exploration, then we open ourselves up to the possibility of expanding our concept of community to include all life, and in so doing, give ourselves a shot at surviving on this finite planet.

EDITOR'S NOTE: A portion of book proceeds will be donated in support of Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative which uses science to help humans and wildlife better coexist in healthy ecosystems. You can purchase the book at tupress.org using promo code NRCC at checkout.