Back to StoriesAre We Ready For The Coming Feral Hog Invasion?

December 5, 2019

Are We Ready For The Coming Feral Hog Invasion?Seriously, while Montana, Wyoming and Idaho are currently free of rogue swine "herds," they're headed this way

Here’s a question I bet many readers have seldom pondered: what’s the bigger threat to our part of the world—native bison wandering out of Yellowstone National Park into Montana or invading non-native feral hogs now entering the state for the first time, crossing the invisible international border from Canada?

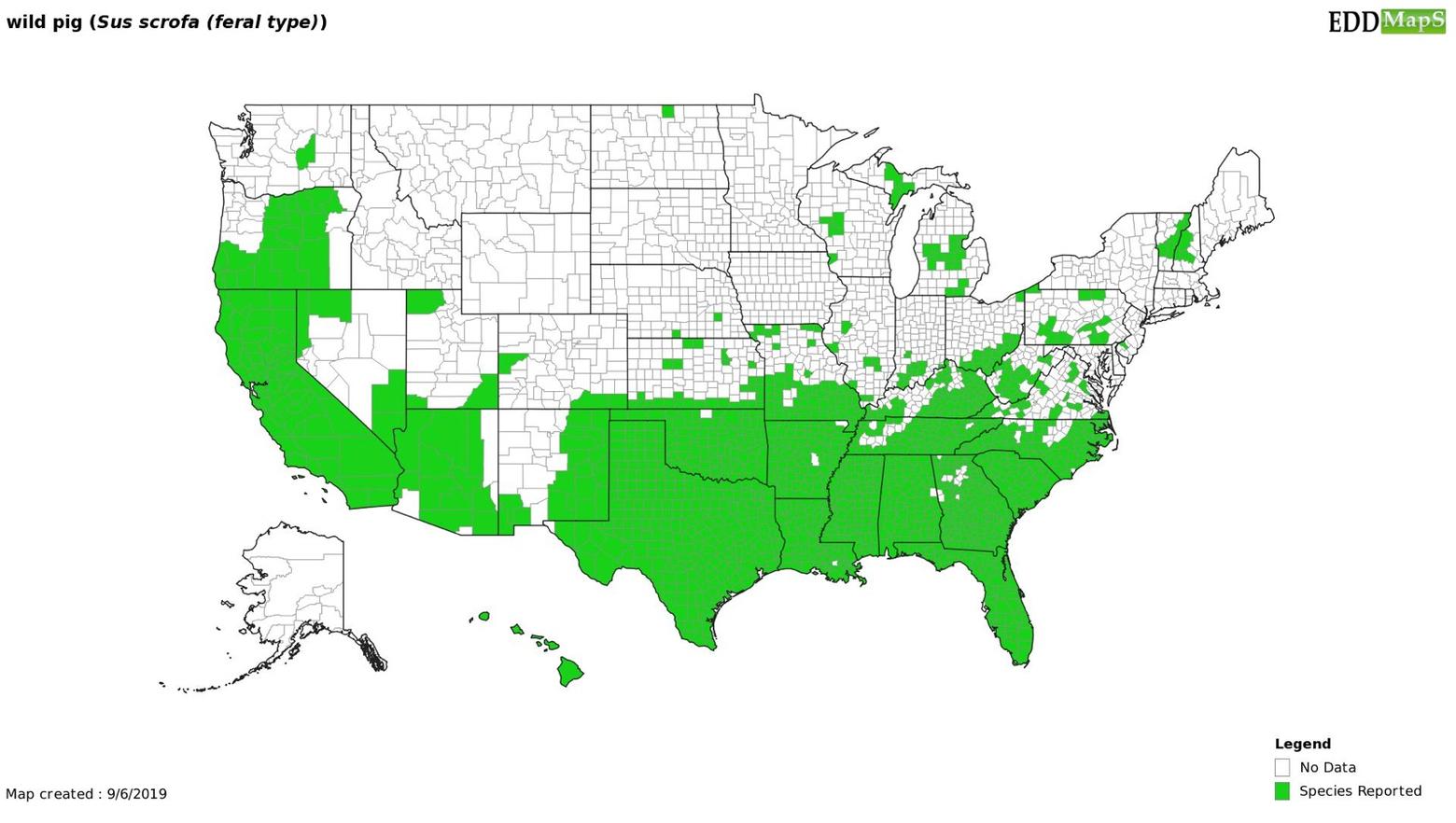

Not long ago, feral hogs were spotted a few miles north of Montana and many experts believe they’ve probably already taken up residence in the rural, remote high plains of the Treasure State. They also are approaching Wyoming and Idaho via Colorado, Utah, Oregon and Nevada.

These undesirable intruders are present in at least 38 states and several Canadian provinces. Originally brought to the continent by Europeans centuries ago, some were turned loose to be a ready food supply while others are descended from non-native domestic hogs that escaped their confinement and reverted quickly to hairy wild boars. (See the photo above; they have an uncanny resemblance to bears).

Like incredibly smart noxious weeds with fleet hooves, big appetites for other things, and tusks, “wild” pigs that get well established can wreak havoc. Their rooting behavior and voracious appetites have caused serious impacts to cropland, stream corridors, native plant communities and both ground-dwelling wildlife and nesting birds. They also carry diseases and viruses such as swine brucellosis, foot rot, intestinal maladies, salmonella and a form of Herpes—many of which can be transmitted to livestock, wildlife and/or humans.

Like incredibly smart noxious weeds with fleet hooves, big appetites for other things, and tusks, “wild” pigs that get well established can wreak havoc.

The US agriculture department estimates that feral hogs cause more than $2 billion in damages annually.

Once they take hold their elusive nature and high reproductive rates make it difficult, if not impossible, to eradicate them. Biologists say that sows produce an average of six piglets in a litter and they breed year round with a gestation period of less than four months.

You may have read a recent newspaper story about a 59-year-old woman in Texas who was attacked and killed by an aggressive herd of feral hogs as she headed to work. Yes, razorbacks prey on other animals, though incidents like the one above are rare.

For the record, that fatality is one more person than was killed by grizzlies in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem this year and more than the total number of human deaths caused by wild wolves in the Lower 48 going back a long, long time.

Montana doesn’t really have a strategy to engage the porcine menace, yet. Aerial flyovers of the US-Canada border area have been conducted. Earlier this autumn the state wildlife and livestock departments, along with the Montana Invasive Species Council, announced a new program called “Squeal on Pigs” that encourages people to report any feral hog sightings.

Nick Gevock of the Montana Wildlife Federation said at a recent "summit on feral swine" in Billings that while he’d love to have hunters enlisted to control the hogs, that alone will not repel the likely coming swarm.

In several states, there is open season on hogs, no license required. As the website Vice reported in its story "Feral Hogs Are Tearing Up Texas," in the Lone Star State there is now even tourism operators who ferry “thrill-seeking” clients around in helicopters and let them blast away at hogs for entertainment and supper.

Some 43,000 hogs were shot from helicopters in Texas last year, Vice reported, which represents only 1 to 2 percent of the estimated population there. Some have pegged feral hog numbers in the Lower 48 at between six and nine million. (That's six to seven times the number of native elk in the Lower 48, ten times the number of native pronghorn, and 15 times the total number of bison, though the vast majority of buffalo are on private farms and ranches.

To sustain that number of voracious feral pigs that will eat almost anything, including meat, it means a lot of food on the landscape is being consumed in the form of crops, things wildlife need to survive and even trash.

So let’s return to the initial question. In the big scheme of things, which animal—native bison or non-native pigs— actually poses the greatest threat to the ecological integrity, heritage and economy of the West? In addition to hogs, let’s add the growing threat of Chronic Wasting Disease.

Regarding bison, many millions of dollars have been spent killing more than 11,000 Yellowstone bison when they've naturally wandered into Montana. Yellowstone this month said that it and its government partners intend to remove another 600 to 900 via slaughter, hunting or putting 150 in the park quarantine program with the hope some animals could one-day be transplanted onto tribal lands.

The anodyne-sounding "cull," which is indiscriminate lethal control, will be done to reduce the size of the park bison population from 4900 to around 4000 to help reduce impacts caused by increasing numbers of bison on the Northern Range. But another major motivator is intolerance from the state of Montana which, it should be pointed out, has not allowed bison to fully inhabit terrain outside the park that Montana Gov. Steve Bullock and staff identified as places to give them more room to roam.

Many people don't realize that Yellowstone bison are special—descended from only a few dozen survivors of near-species extinction at the turn of the 19th century. The killing of Yellowstone bison in Montana has been based on the claim that bison represent an eminent threat to transmitting the disease brucellosis to domestic cattle.

Never mind that there has never been a documented case of that happening between wild bison and cattle in the region. Moreover, the nation's leading scientists note wild free-ranging native elk, which also carry brucellosis, are a more serious risk and have actually transmitted disease to cattle in Greater Yellowstone.

Elk, however, are not shot or sent to slaughter when they leave Yellowstone in order to minimize disease risk.

Why does Montana remain so zealously focused on maintaining its intolerance toward Yellowstone bison? That same attitude is rife in the east-central portion of the state where ranchers and politicians assert, without basis in fact, that bison represent a major threat to their livelihoods.

They don’t even want the American Prairie Reserve to be able to graze native bison on public land grazing allotments administered by the federal Bureau of Land Management, saying non-native cattle should hold primacy.

Federal and state governments spend millions of dollars each year shooting, trapping and poisoning native species such as wolves, coyotes, cougars and black bears to make publicly-owned rangeland safer for non-native livestock. They also mandate the slaughter of bison, America’s official national land mammal. Some ranchers admit their resistance to letting bison roam is based more on a bias against them than as a real disease risk.

Yet those same government agencies, many of them devoted to promoting the health of native species, justify the killing of native predators and bison. At the same time, they together have no coordinated plan for addressing the spread of CWD in America's richest large-mammal ecosystem or dealing with feral hogs that, pound for pound, as evidenced by the impacts in other states, represent substantial threats to our hunting, agricultural and wildlife traditions.

Feral hogs are said to have no natural predator, save for humans, but nowhere in the Lower 48 have they been subjected to the full guide of wild native predators that exist only in the Northern Rockies—wolves, grizzlies and black bears, cougars and coyotes.

Like many issues in the 21st century West, there seems to be a pandemic of misguided priorities at the same moment that a number of transformative forces converging on the landscape. We slaughter bison based on a rumor of disease and stand by and watch the progression of CWD while simultaneously the invasion of destructive disease-carrying hogs is occurring right before our eyes. We treat their arrival almost as inevitable and don't ever seem to take serious action until there's a crisis when often it's too late.

Why is that?

Then again, for Western rural communities on the high plains struggling to survive in the rugged middle of nowhere, maybe screaming soo-ey! , as they now do in Texas, will become the battle cry for new helicopter tourism. What's for dinner? It won't be beef, bison or pronghorn, but "wild" pork chops. Some say they taste as good as chicken.