Back to StoriesGrizzly Matters: A Recap Of Court Actions Involving Greater Yellowstone Bears

January 6, 2019

Grizzly Matters: A Recap Of Court Actions Involving Greater Yellowstone BearsWhen it comes to true recovery for America's most famous bruins, the focus is not on numbers but biological connectivity

As the winter Solstice arrived in late December, just 10 days shy of the end of 2018, the US Fish and Wildlife Service gave notice that it may appeal a September federal court ruling that overturned removal of Endangered Species Act protections from the Greater Yellowstone grizzly bear population.

That ruling, issued by US District Judge Dana Christensen in Missoula, Montana, put Yellowstone-area grizzlies back under federal protection. The case was brought to court by a coalition of Native American tribes and conservation groups.

While the Constitutionally-guaranteed right to challenge government decisions in court is a cornerstone of freedom, making policy via the courts is inherently limiting. Wading through the ruling’s 48 pages of legalese might expand your vocabulary, but you probably won’t come away with a clear understanding of where grizzly conservation in contiguous states is headed.

A court decision can only deal with what’s in the law, the arguments that the litigants raise, and with previous court decisions. While authoritative, the constraints of the judicial system don’t allow for a rich, creative dialogue among people with different points of view about the survival of large carnivores. To have that kind of future-shaping discussion, people need to step outside the rigidity of the courtroom, and reckon with what it means to share our region with grizzlies.

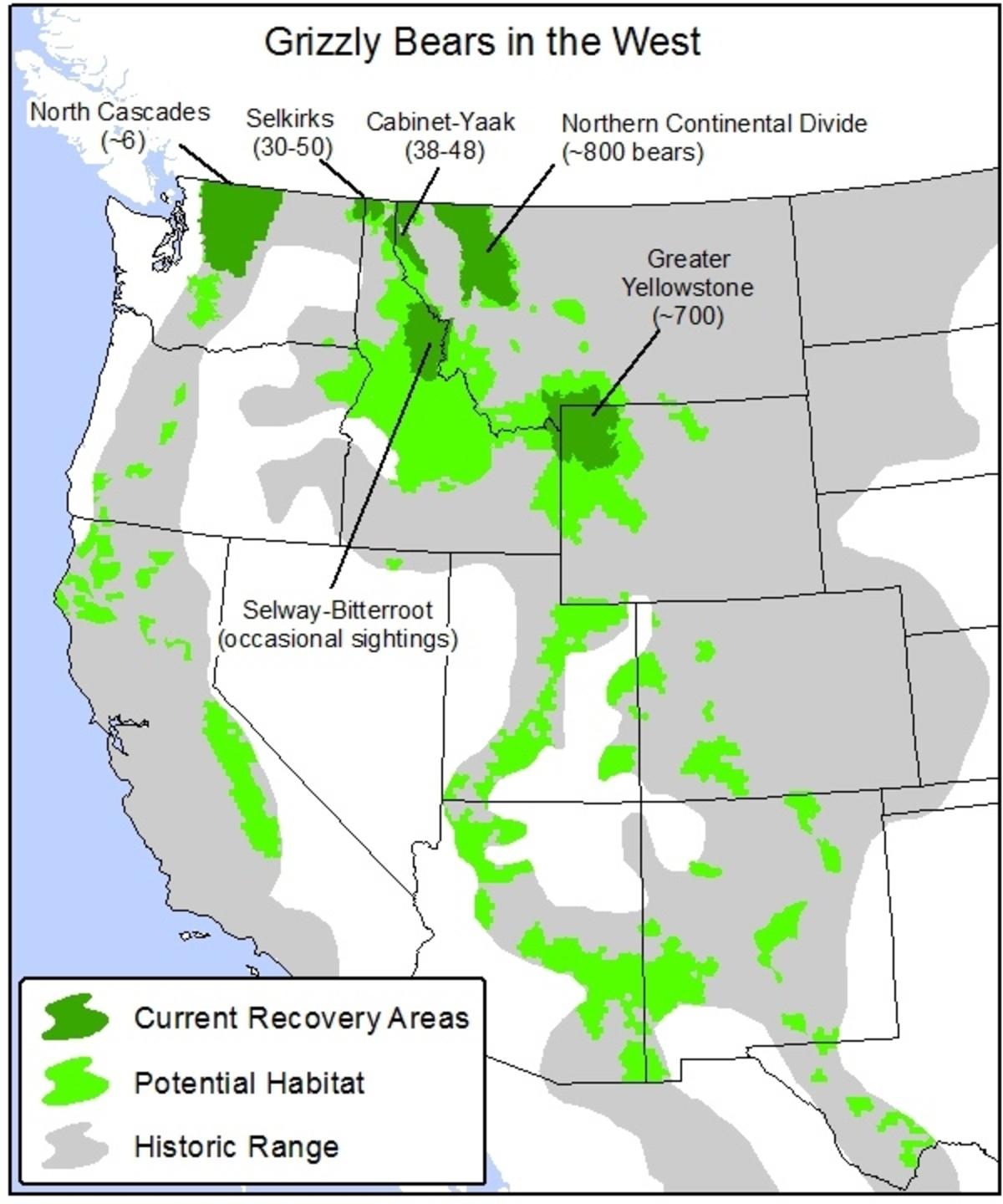

Judge Christensen’s decision speaks to three major issues. Of those, two stand out, and are intertwined like the double helix of a DNA molecule: the issue of the Yellowstone grizzly population’s isolation from any other grizzlies is the first, and the requirement that the Fish and Wildlife Service carefully analyze how delisting this geographically isolated population will affect the other threatened grizzly populations in the lower 48. (The third issue, involving the selection of statistical methods for estimating the grizzly population, i.e. counting bears, is important but not as momentous as the other two).

In many respects, though this court case was superficially all about Greater Yellowstone’s grizzlies, the judge’s ruling could carry equal significance for another grizzly bear recovery zone: central Idaho’s presumably vacant Bitterroot Grizzly Bear Recovery Zone.

Central Idaho was once superlative grizzly habitat, with thriving salmon runs, abundant berries, and plentiful whitebark pine seeds. Unfortunately, the grizzlies were wiped out by 1932, and the salmon runs have been devastated by downstream dams and overfishing. Whitebark pine has dwindled away due to a non-native fungus and climate-driven outbreaks of beetles. Still, this amazing chunk of country has what grizzlies need to thrive: remote, wild space where there will be few conflicts with us.

The Bitterroot Ecosystem was officially identified as a recovery zone in 1975, when Lower 48 grizzlies were protected as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act. In the intervening decades, there has been no conclusive evidence of grizzlies in the area, yet a few grizzlies have come tantalizing close.

In the 1990s, the Fish and Wildlife Service plan was to transplant grizzlies from other healthy populations into central Idaho. Still brooding over the high-profile reintroduction of wolves into Greater Yellowstone and central Idaho, conservative politicians mobilized against the proposal, rallying opposition and cutting off funding. With the inauguration of President George W. Bush in 2001, the reintroduction plan went into dormancy, where it remains today.

Reintroduction could still happen, though there are stronger arguments in favor of simply letting grizzlies walk to the Bitterroot on their own. First, reintroductions are controversial, as both the mid-1990s wolf reintroduction and the stalled Bitterroot grizzly plan demonstrate. And for all that controversy and expense, trucking grizzlies to central Idaho could very well create yet another isolated population that would need constant intervention to stay viable.

Ecologically, a gradual process of letting grizzlies expand into the Bitterroot from Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Continental Divide (which includes Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness) would allow bears to adapt to an unfamiliar habitat over a few bear generations, rather than being plucked from familiar environs and dropped off in new country 100 or more miles away.

Grizzly bears are already moving toward the Bitterroot; still, we can’t divine where their wanderings will ultimately take them. They are moving south along the spine of the Sapphire Range from the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem; they have appeared in the upper Big Hole Valley, within 50 miles of the Bitterroot’s official boundary. And Greater Yellowstone’s grizzlies continue to push westward, in a direction that could put them on course to reach central Idaho.

It’s this latter Greater Yellowstone connection that is particularly intriguing: currently, the grizzlies of the world’s first national park are utterly isolated from others of their kind. Although this population has made a remarkable comeback over the past 50 years, isolation still poses threats. Besides the well-known threat of an inadequate gene pool, barriers to connectivity can also prevent these bears from spreading out and adapting in response to changes in their natural food sources.

Greater Yellowstone grizzlies have already experienced the loss of some key foods, most notably the climate-change driven loss of whitebark pine from much of the ecosystem. About the only alternative foods that have similar nutritional value to whitebark seeds are ones that get grizzlies into deadly trouble: big game meat (problematic because they’re competing with hunters for it) and livestock (because they are someone’s property and livelihood).

These grizzlies need the wild freedom to adapt by recolonizing unoccupied habitat. They need to re-connect with other grizzlies so they can thrive as one big, robust population. And through that process, we can keep the promise made 44 years ago to recover grizzlies in central Idaho, too.

Judge Christensen’s ruling makes it very clear that the Fish and Wildlife Service needs to ponder the re-connection question: the decision clearly insists on a meaningful plan to address the threat of isolation to the Greater Yellowstone population, and calls for careful consideration of how delisting this population will affect grizzly recovery elsewhere in the Lower 48.

Consider these key points above alongside 44 years of inertia on restoring grizzlies to the Bitterroot: reconnection is the obvious path forward. It would address Yellowstone’s isolation, help grizzlies recolonize the Bitterroot, and compellingly show that the agencies are considering all of the lower 48 grizzlies, not just one population split off from the rest.

° ° °

After Judge Christensen delivered his decision, it was appealed by the states of Wyoming, Montana and Idaho as well as the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, Safari Club International and the National Rifle Association, all of which have supported the restoration of trophy hunting of Greater Yellowstone grizzlies.

Again, the Fish and Wildlife Service in late December only reserved its ability to join the states in appealing but it did not commit to do so. The question now is whether it will re-explore the reasoning behind its decision to support removal of grizzlies from federal protection.

If the Fish and Wildlife Service goes back to the drawing board, rather than appealing, to address Judge Christensen’s key points, there are some important steps the agency could take to constructively respond.

Perhaps most importantly, the Fish and Wildlife Service can set forth a strong vision for the re-connection of Lower 48 grizzly populations, starting with Greater Yellowstone. A strong affirmation of the value of re-connecting our grizzly populations would be a departure from the ambivalence of past policies. People who would be sharing space with returning grizzlies deserve a clear explanation of the why, where, and how of these efforts.

It’s one thing to say we should establish connectivity among the scattered grizzly populations of the Lower 48. The hard part is making that happen. We are talking about grizzlies moving back into places they haven’t been in close to a century. The only way this will work out is if people come together to prevent conflicts and promote bear-safe practices in these places.

Fortunately, in most of the landscapes that could reconnect grizzly populations, there are already many conflict prevention programs underway, with co-existence being a unifying goal. These are collaborative efforts involving ranchers, hunters, seasonal residents, watershed groups, wildlife advocates, and state and federal agencies. From backcountry camps to ranches to subdivisions, people are working together to figure out how to prevent conflicts with grizzlies.

A recent paper by Canadian and American grizzly biologists demonstrates a clear link between conflict prevention and restored connectivity between isolated grizzly populations where Montana, Idaho, and British Columbia meet.

Anyone involved with grizzly conflict prevention (as I have been for over two decades) knows that the work is never finished. New people move in and need to get up to speed on living with wildlife. Bear-resistant garbage cans wear out, electric fences need maintenance, and livestock carcasses need to be hauled to secure composting facilities. As grizzlies and other carnivores recover and expand, we need more of these programs across the region. Yet the resources to keep up are scarce, and there’s little left over for harvesting and sharing lessons among far-flung project sites.

The Fish and Wildlife Service has contributed crucial support and expertise to many of these conflict prevention programs. To keep up with the expanding and perpetual demand, though, sufficient and stable funding—a reliable commitment— is necessary.

Let me offer a proposition: by making grizzly reconnection an explicit, essential part of the path to delisting, the Fish and Wildlife Service would imbue coexistence efforts with a stronger sense of purpose and urgency. Ideally, a firm commitment to reconnection would attract substantial private and public funding to sustain and expand coexistence programs.

Some will argue that such a bold move would cause “backlash” needlessly. Consider, though, that some Westerners have spent the last 30 years prophesying plots far more sinister than giving out bear-resistant garbage cans and bear spray. And it’s worth pointing out that there are at least a few grizzlies already known or suspected to be living in most of these reconnection zones, often without incident. Inadequately-supported conflict prevention will only serve to prove the nay-sayers correct in their claims that we can’t live with grizzlies.

Judge Christensen’s ruling may have stung the Fish and Wildlife Service and the three states that converge in Greater Yellowstone when it came out. Then again, we might view it as an opportunity.

Across the spectrum, people who have worked to recover grizzlies have much to be proud of. Bears have expanded in numbers and in range beyond what many could imagine. And roughly four generations of bear conflict prevention pioneers have made great strides in improving how we live with these compelling beings.

Perhaps, here in the depths of winter, we can all pause and take stock of where we are, and where we could go. Somewhere, in a snug den high on a ridge in the Sapphire Mountains, a grizzly may be having the same dream.

PLEASE SUPPORT US: Mountain Journal is committed to giving you reads you won't get anywhere else, stories that take time to produce. In turn, we rely on your generosity and can't survive without you! Please click here to support a publication devoted to protecting the wild country and the wildlife you love.

Related Stories

September 23, 2017

Grizzlies Deserve More Than Bullets

Phil Knight saw his first Yellowstone grizzly 35 years ago. After watching bear numbers climb, he says recovery should not be...

November 1, 2017

When An Off-Duty Game Warden Kills A Grizzly

After a mother grizzly with three cubs is shot in Wyoming, critics wonder why the person, who invoked self-defense, didn't use...

October 26, 2017

Lessons Learned From A Hunter Attacked Twice By A Grizzly Bear

The Incident Involving Todd Orr In The Madison Mountains Offers Insights For Those Chasing Big Game And Adventure In Bear Country...