Back to StoriesLearning, To Care Deeply For Mother Nature

August 14, 2018

Learning, To Care Deeply For Mother NatureIn Montana's Centennial Valley, the Taft-Nicholson Center opens minds for life by immersing students in the wild unknown

It’s 6:30 am, and in the old town of Lakeview, Montana, a bird-watching walk is in order. Long shadows still blanket the dusty former logging road, but the morning sun lights up the porch of a rough-beamed building where a dozen undergraduates have assembled. They wear hats, leggings, long-sleeves, and, even at this hour, ample bug spray. At this time of year, they’ll probably need it all day long.

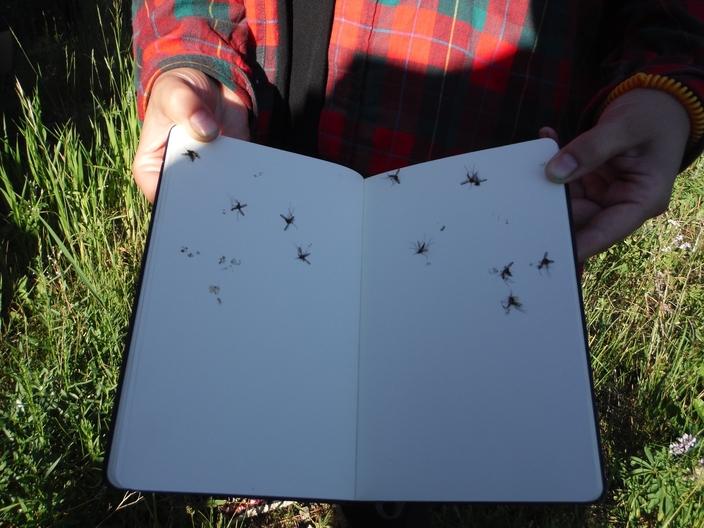

They flip through their notebooks while they wait for the walk to start, and as they do I catch glimpses of little wonders: drawings of dragonflies and butterflies with chromatic wings, colored sketches of pinecones and aspens, and notes written in flowing calligraphy that puts my own hasty scribbling to shame.

These dozen art students have brought their talents to the Taft-Nicholson Center, an educational complex nestled against the beautiful Centennial Mountain range in southwestern Montana and operated by the University of Utah. As a liberal arts field station working to spark the flame of naturalism and stewardship in its students, no other place like it exists in this remote yet spectacular corner of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

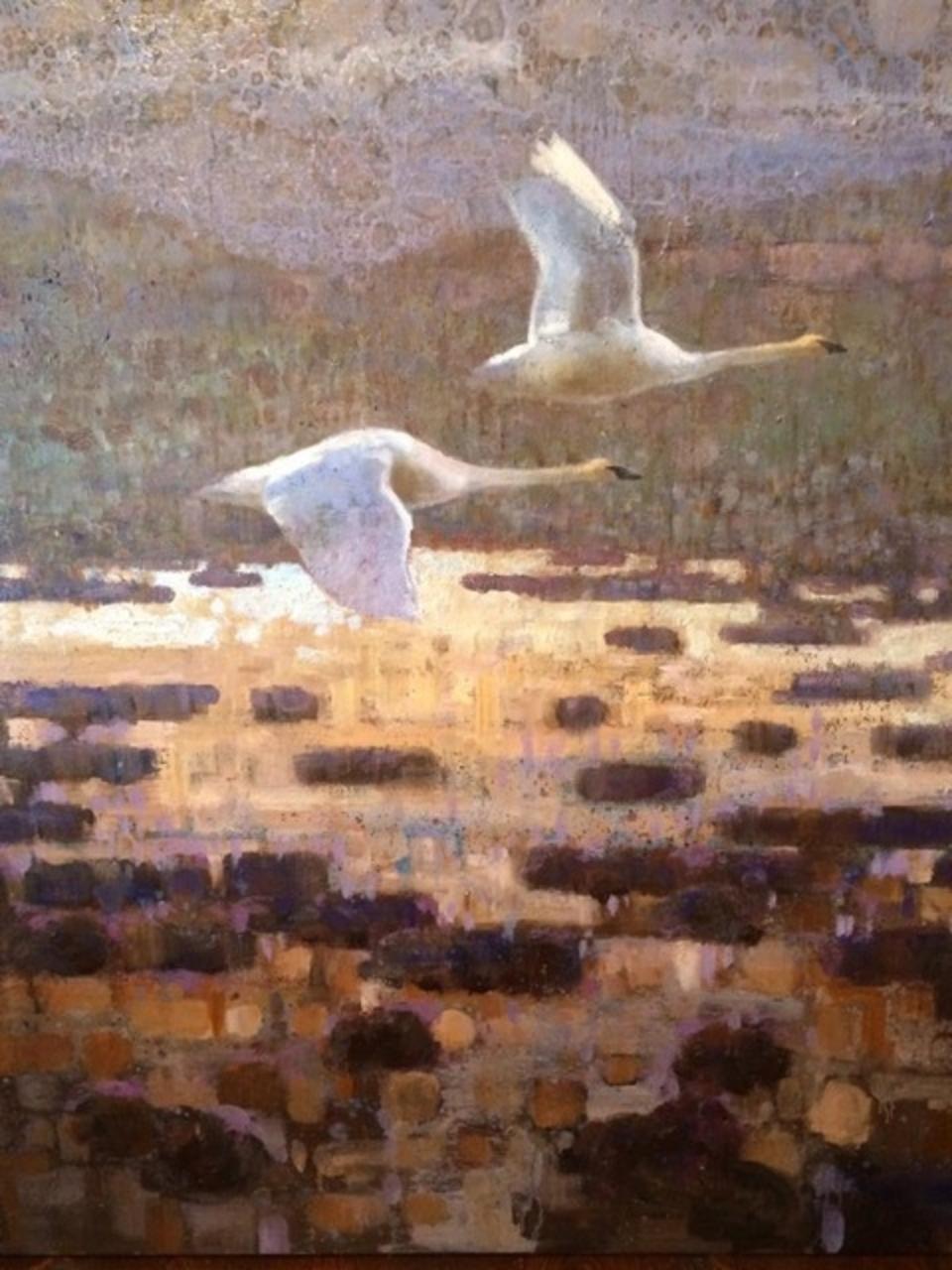

The Center occupies the former settler-farming outpost of Lakeview, near the tarns at the heart of Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge — a preserve that made history protecting trumpeter swans from extinction. During their 10-day stay here, students will immerse themselves in the landscape around them through their own artwork, and, as their notebooks reveal, none will do so in exactly the same way.

Though focused on the humanities, the Taft-Nicholson Center hosts courses on a variety of topics ranging from climate communication and environmental leadership to geology, ecology, and conservation biology. STEM students come to complete capstone projects. Science teachers and conservation leaders also converge here, utilizing the setting to make environmental education more real and visceral in an age when what Richard Louv calls “nature-deficit disorder” runs rampant.

Ideally, by exploring the natural world around them through the lens of their chosen discipline (and vice versa), students discover how that world matters to them on an intimate, personal level.

That’s what this place is about. In the words of the Center's director Mark Bergstrom, “Our mission is to increase environmental literacy, boost environmental awareness and inspire personal connection to nature and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem” — all while studying in “one of the most remote valleys in the West, unplugged from the modern world.” Unplugged is the operative word.

The venue for this endeavor came through the generosity of a few local landowners and benefactors. In 2005, John and Melody Taft came together with William and Sandra Nicholson to purchase and renovate Lakeview — no small undertaking, to say the least. They then donated it to the U of Utah for use as an environmental education center.

Today, the Taft-Nicholson Center retains an old-fashioned look, like the set of a classic Western with false front architecture and shady porches bordering a dusty main street. The buildings, however, have been refurbished and repurposed into classrooms, dormitories, offices, and a cafeteria-style dining hall with a welcoming fire pit outside. To the north stretches the sea of open space at the heart of the refuge.

John and Melody Taft live just up the road. Through this, their desire to give back to this magical dell has come alive. Mr. Tafts's dream started more than half a century ago when then, as a young naturalist from California about the same age as the students are now, he arrived with eyes wide open.

A young cinematic prodigy of sorts, he was making films circulated by the National Audubon Society and shown in movie houses and gymnasiums nationwide. Eventually he and Melody got married and built their home, replete with a botanic mosaic of native wild plants. It's a retreat that once harbored the original founders of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition as they crafted a vision for protecting the larger ecosystem in the 1980s. Numerous other influential conservation leaders have also discussed issues of the day on the Taft lawn.

More importantly to the Tafts (and to the students), the surrounding private and public land remains undeveloped. (Click on the video profile of them at the bottom of this story). The Center sits in the sweeping Centennial Valley, a crucial connecting corridor for wildlife movement and migration within Greater Yellowstone and a link to wildlands stretching northward into the high divide of Idaho and northern Montana and southward toward the Tetons and mountain stretching clear to Utah.

The valley also contains the largest wetlands complex in Greater Yellowstone, most of which is encompassed by the national wildlife refuge, and is home to animals ranging from moose, pronghorn, grizzly bears and wolves to swans, bald eagles, osprey, Northern Goshawks and a vast array of other birds. More recently, refuge manager Bill West and his staff have worked with the state of Montana to restore arctic grayling and westslope cutthroat trout.

Behind the center looms the Centennial Mountains Wilderness Study Area, stewarded by the Bureau of Land Management. If a recent bill written by U.S. Rep. Greg Gianforte is passed into law, this area could be opened to wide range of multiple use activities, including logging, mining, motorized recreation, and mountain biking.

For now, however, the wilderness of the public lands and the presence of about a dozen major ranching families running cows instead of building condos makes the Centennial a rare counterpoint to the kind of development moving rapidly into other valleys in Greater Yellowstone. In recent years, a number of ranchers have worked with The Nature Conservancy to put conservation easements on their land, insuring that some of the unblemished views stretching twenty miles across or more will remain as they are today — as they have been since the glaciers retreated millennia ago — forever.

For students, this creates an outdoor classroom like no other.

By the Tafts’ design, a visit to the Center intends to plant the seed of personal transformation, shaping not only how students understand the wild West but how they ponder their own roles in helping it persist.

Mark Bergstrom recalls the words of a med student who initially considered the curriculum of the Center trivial and irrelevant to his area of study: “I had no intention to make any heart-pings with the trumpeter swan.” Eventually, however, this student began to see the landscape in a new light. “Before I saw the sun spill across the horizon and onto Swan Lake, I thought all nature was the same. [...] I was blind to the little things,” he said. “Like ordinary society, the valley was gilded with an ecological atmosphere so dense that only those who knew what they were talking about would see the issues within it.”

Like the aspiring doctor, the art students I meet with get a breadth of experiences most in their discipline wouldn’t receive. Some had never picked up a paint brush before but through tutelage and encouragement, their plein air studies—artworks painted in the field amid ambient sounds, clouds in the sky and wildlife moving around them—speak to their own sense of connection.

At the Taft-Nicholson, students from 2017 take a deep dive into place through painting (see video below, shot with iPhone by Todd Wilkinson)

Professor Kim Martinez, who has led a series of summer pilgrimages to the valley, says learning how to see a landscape as a painter quickens the bond and adds another interpretive language to their repertoire, one they will speak for life. After all, it should be noted, a number of prominent American naturalists, including elk biologist Olaus Murie in Jackson Hole, contributed their own artistic sketches to illustrate field guides.

“Part of my goal in creating this class is that they’re doing landscape painting but also learning about landscape ecology,” Martinez says. “Days before we were dealing with cartography, making maps, and the kind of art and science that goes in with that.” By covering a range of topics, Professor Martinez aims to provide her students with multiple sources of inspiration for their art.

“We stand in one spot and we look at a place for like eight hours,” Martinez adds, “so in many ways it’s about becoming one with the space.” That’s an experience that many students who hail from metropolitan areas have never had. The Taft-Nicholson center offers no cell service or internet. Even sunrises, sunsets and night skies become revelations, as does the quieter, slower pace of life. Whether catching a glimpse of a pronghorn down the trail or paddling a canoe over a lake, students discover that open spaces are not empty but filled with unseen wonders.

Over the years, a remarkable roster of guest faculty and artists in residence have also graced the Center, including Terry Tempest Williams, Rick Bass, Doug Peacock, world-renowned geophysicist Dr. Robert Smith (the guru of the Yellowstone caldera), painter Ewoud de Groot and contemporary Montana landscape painter Dave Hall.

I spoke with two former artists in residence of the Taft-Nicholson Center, Sara Tabbert (a visual artist) and Gretchen Henderson (a writer). Tabbert describes the experience as “a very good combination of solitude and company,” and both say the Center gave them a quiet, private space to slow down and focus on their work — a valuable luxury for any artist. At the same time, they appreciated the company of students, scientists, ranchers, and others doing interesting work entirely different from their own.

When asked why it’s important for artists to connect with spaces like the Centennial Valley, Henderson riffs on the power of place.“In the past when I have done artist residencies, I have brought projects that don’t relate to a residency’s particular location,” she says. “This was the first time that I worked on a place-based project that seemed organically linked to the landscape. [...] A place’s rhythms work into the rhythms of writing.”

Tabbert agrees, encouraging artists to slow down to truly appreciate that sense of place. “All places are complex, and without that time it is easy to not only miss many of the things happening in the natural world, but also completely miss the inevitable complexities that people's competing interests and agendas have brought to a place.”

The Center’s associate director Lucas Moyer-Horner, a biologist who once studied pikas in Glacier National Park, concurs. “Continued scientific investigation of these topics is important, but scientists alone cannot solve these problems,” he says. “It's going to take large cultural shifts and sociopolitical action. Here, the humanities are essential. We must find ways to transcend our cultural identities and biases and work together to preserve the fundamental and wondrous ecosystems that preserve us.”

Like the artists, I too have come here to learn — as a student of environmental humanities, for one, but also as a newcomer to Greater Yellowstone. This trip is my first real venture into this vast iconic landscape, and it stands in stark contrast to a typical tourist’s first Yellowstone experience.

The Centennial Valley is not as flashy or otherworldly as Mammoth Hot Springs, nor does it have herds of elk wandering the lawns for hoards of tourists to stop and gawk at, so much like a zoo. You don’t just drive in, take a few selfies, grab an ice cream, and then get back into your air-conditioned SUV with the tunes blasting. It’s not that sort of place.

Instead, it’s meditative — vast grasslands and wetlands slope gently but swiftly into mountains, creating a space that feels open and free yet also safe and secluded. It doesn’t scream for your attention; it asks for your patience. It invites you to take time to be present with all your senses. The elk and moose won’t magically appear before your car window — you’ll have to wait and wander a bit before you see them. The reward is a slower but richer experience.

While at the Center, I have the good fortune of tagging along on one of the students’ favorite activities of the program: the early-morning bird-watching walk mentioned above, led by Dr. Jack Kirkley from the University of Montana-Western.

Dr. Kirkley outfits each student with a pair of binoculars before leading them up the hill behind the guest cabins. For each bird we see, he lists the “field marks,” or identifying traits, of the species. Behind him, a dozen binoculars point up in the same direction.

When we find a woodpecker, Dr. Kirkley replicates its song — “de-de-de-de-de” — with his own voice. Then he points out the old snag the bird clings to. This tree might have died, he says, but it remains important as a means of shelter and food storage for woodpeckers and other birds, and may stay in use for fifty or even a hundred years.

I can’t help but think of the Taft-Nicholson Center in a similar way. The old ghost town of Lakeview must have thought it had seen its dying day long ago. Today, however, it’s been given a new purpose, still used by these “birds” to make art, to imagine, to create, and to train young environmental leaders for the future.

Interdisciplinary approaches, director Bergstrom feels, define environmental humanities. “We train ourselves and our students to make sense of the world from a variety of perspectives [and] to do so in a critical and informed way.”

Epiphanies need not always be immediate. What effect will a journey to the Centennial Valley have on a student’s perspective in fifty years? If the largesse of the Tafts and Nicholsons is any indication, this sort of nurturing experience can plant an epic desire to give back.

For the undergraduates I spoke with, the power of connecting their art with the landscape had not yet become as clear as it has for experienced artists like Tabbert and Henderson — they’d only been at the Center a few days, after all, and not all of them were experienced painters. Many applied to the course on a whim or at the recommendation of a professor.

Henderson would tell them that’s normal, and that the ripple effects of an experience like this can take time to manifest. “It’s like touching the Missouri River headwaters at Hell Roaring Creek in the Centennial Valley and realizing that same water may end up in the Mississippi Delta and the Atlantic Ocean,” she says. “You have to be patient enough to follow the meandering course.”

EDITOR'S NOTE: By the time they are finished, the art of place becomes embedded in their psyche and offers a new way of relating to the world (video by Todd Wilkinson with iPhone). To learn more about Melody and John Taft, founders of the Taft Nicholson Center, also enjoy the short video documentary, below, made about their passion for nature when they were recognized as honorary alumni by the University of Utah.

Related Stories

July 23, 2018

A Millennial Navigates The World Unplugged

MoJo intern Sean Cummings went to a high school where digital trappings were forbidden, by design