Back to StoriesImagine Foreign Invaders Coming Into The Land

January 26, 2018

Imagine Foreign Invaders Coming Into The LandPoet Lois Red Elk serves as translator on a road trip and pays homage to Ella Cara Deloria

Before the immigrants came, speaking their foreign languages, bringing with them unwanted violence and menace justified by a religion and values that seemed strange to them, Lois Red Elk's ancestors were eating wild rice and walleye and venison and pemican this time of year in the North Woods and tall grass prairie of the western Midwest. In the summer, they would move onto the plains and join their cousins on buffalo hunts, sharing an affinity that transcended everything.

It was the old home land.

"My first memory of language was hearing my grandmother’s Hunkpapa stories. Such a joy to have that rich experience. As I grew up other languages became integral parts of my being. My mother spoke Dakota/Lakota, Assiniboine, French, English, some Latin and some Anishinaabe," Red Elk shares. "I enjoyed watching mother listen to the French/Canadian radio coming from Regina, Saskatchewan. Her joy. My role with language is to understand the depth of human nature and being conveyed in my language. I share two poems for you to translate for your understanding."

In the works that follow, the distinguished Dakota/Lakota poet serves as translator, sharing with us how an indigenous guide might, in her or his own native tongue and dialect explain the details of a modern roadtrip. Enjoy the piece, "Trespassing in English."

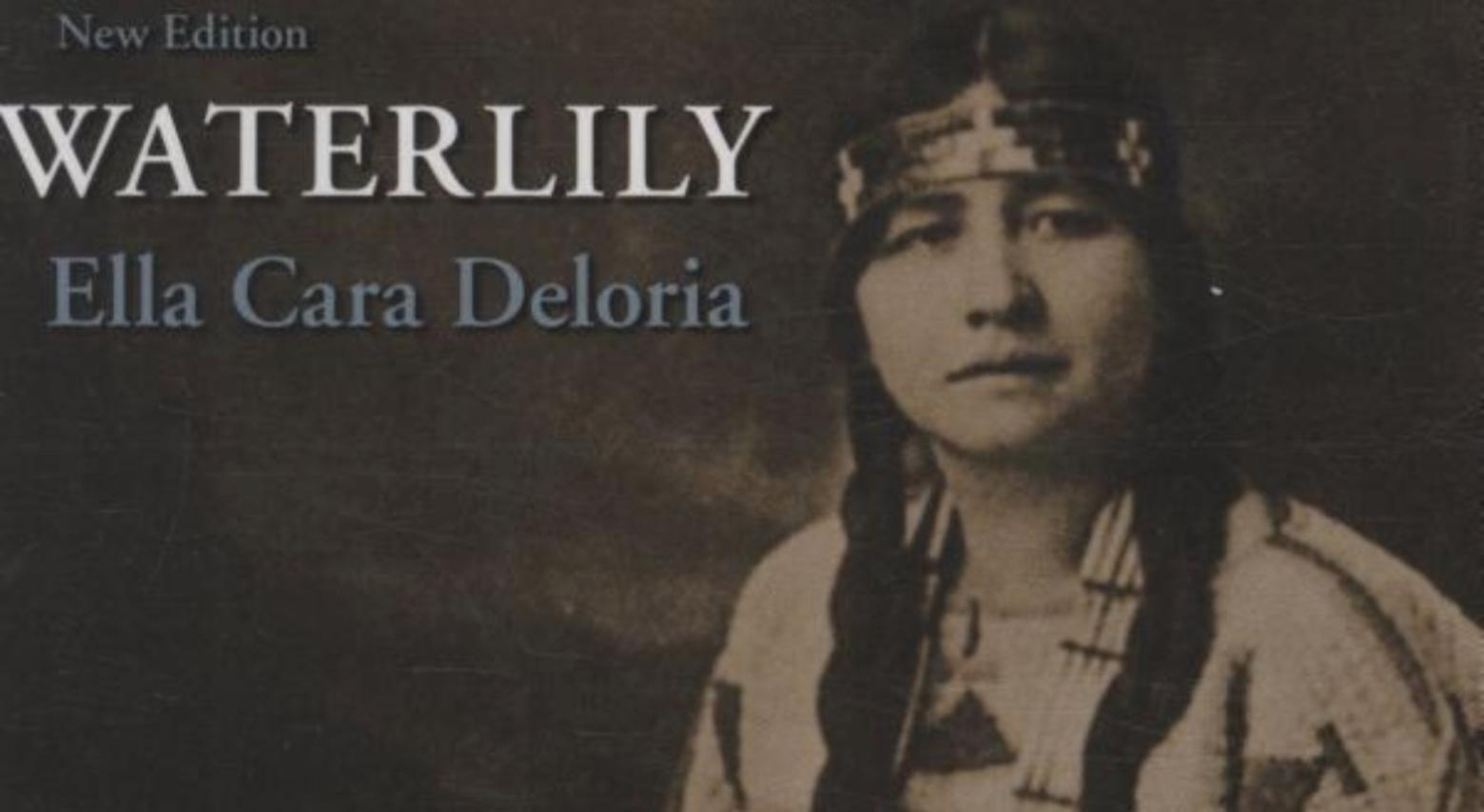

Ella Cara Deloria, aunt of the theologian, historian, lawyer, activist, professor and author Vine Deloria Jr., who wrote the acclaimed 1969 book, Custer Died For Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto.

Ella's given name was Aŋpétu Wašté Wiŋ (translation: "Beautiful Day Woman"). Deloria (January 31, 1889 – February 12, 1971) was a widely-respected linguist, educator, anthropologist, ethnographer and novelist who wrote the book, Waterlily, published posthumously and several others as well as magazine stories. "Ella wrote about the Dakota language and hundreds of stories in Dakota with translations," Lois says.

Like Red Elk, Deloria has a fascinating background and she played a crucial role in helping to save Dakota language by moving it from spoken word onto the permanent written page. With connotation and attachment to the places of their origins, however, words lose meaning and must be put into practice besides just being spoken.

Deloria noted time and again that her own language, culture and worldviews did not need outside validation by those who came to North America. It was as special, sophisticated, poetic and insightful as any other on Earth and she believed it was the same for every tribe and language on the continent.

Nothing is simple but there is a grounding in knowing where you came from, and how original words are super-loaded with the essential meaning of existence. In her poem, "I've Been Reading Deloria," Red Elk riffs on Deloria's wisdom that culture is carried forward in the survival of language. Read her pieces first by paying attention to the stories then again and again gleaning their broader allusions. —MoJo Editors

By Lois Red Elk

TRESPASSING IN ENGLISH

Told you were wicistinma (sleeping), a dormant form

just now giving up your hibernation. Wetu (Spring)

started without you. Mahpiya (a cloud) squeezed rain

over your roof and hurried past that West Coast

hanyetuwi (moon). Inside your humble tipi (home),

a television announcer exchanges and bargains in English –

a solid drone of wasicu (white…) noise encroaching on

your canku (path) to dreaming in Dakota (Sioux). I hear

your partner try to wake you. “You’re wanted,” (on the

phone), “They need you,” (to pick up), words traveling

through veins of another kind, rushing along Highway 2,

across tin’ta (the prairie) at the speed of light into the

receiving end of my waiting makamibe (world). Inside

my receiver that local train, switching through your

otonwahe (town or village) is heard in Montana. It

breaks a short whistle (short of me hanging up). I place

myself in your taku o’ksan un (environment), see an

uneasy pose, blinking at the waiting anpetuwi (sun),

head hanging off the edge (of the bed). An extremity

flinches like you trying to stop a fall, or you taking flight –

a late rendezvous with muscles trying to let go (of sleep),

then giving in to waking (in English). You open your

eyes, wonder why it’s wikawankap’u (around seven or

eight a.m.), wonder who is calling so early? It is just your

koda (friend) and spring in kicieconpi (competition) with

the t.v., and that train, trespassing your space in English.

© Lois Red Elk

° "Trespassing in English" is included in the volume, Our Blood Remembers, 2011, Many Voices Press, Kalispell, Montana, 59901

I'VE BEEN READING DELORIA

I’ve

been reading Deloria’s Dakota Text lately in

a

necessary but nihinciya (nervous)

move away from

reading,

writing, hearing and speaking English.

This

constant breathing in English has made my

brain

aogin (dimmed), me in limbo with head

pain.

I’ve

been missing the words and sounds of my

mother

and her sister speak Isanti the Wahpe Kute,

of

living by the knife and shooting among leaves.

The

colorful verbs I experienced and the denoting

root

words growing from earth that energize my

balance,

my existing in space. It puts my

thinking

back

in wogligleya (a pattern), where

sounds and

meaning

exact the honest perspective of the here

and

now, the language of my childhood, where life

happening

at the moment is exclaimed as part of

the

natural order where life will return in circles

lifting

me to the age which includes grandmother

earth,

seasons, plants, wamakaska (beings of

the

earth-animals)

elements of air referred to as kin,

as

family beings. This is the living earth language

I

miss, where all our senses are exacted and

accepted

with and among animal/plant tongues.

When

did such a separation from affinity seduce

me

to accept English as my wokunze, a

standard,

without

me questioning the loss? Where in the

process

of my wouspe (learning) did a book

collide

with

how I learned and I never knowing the actual

experience? Hicena,

I will find that continuance

state

with Deloria for a while, as a refreshing drink

of

water and remember our place is forever.

©

Lois Red Elk