Back to StoriesThe Future Of The Local Small Town Ski Hill

February 1, 2018

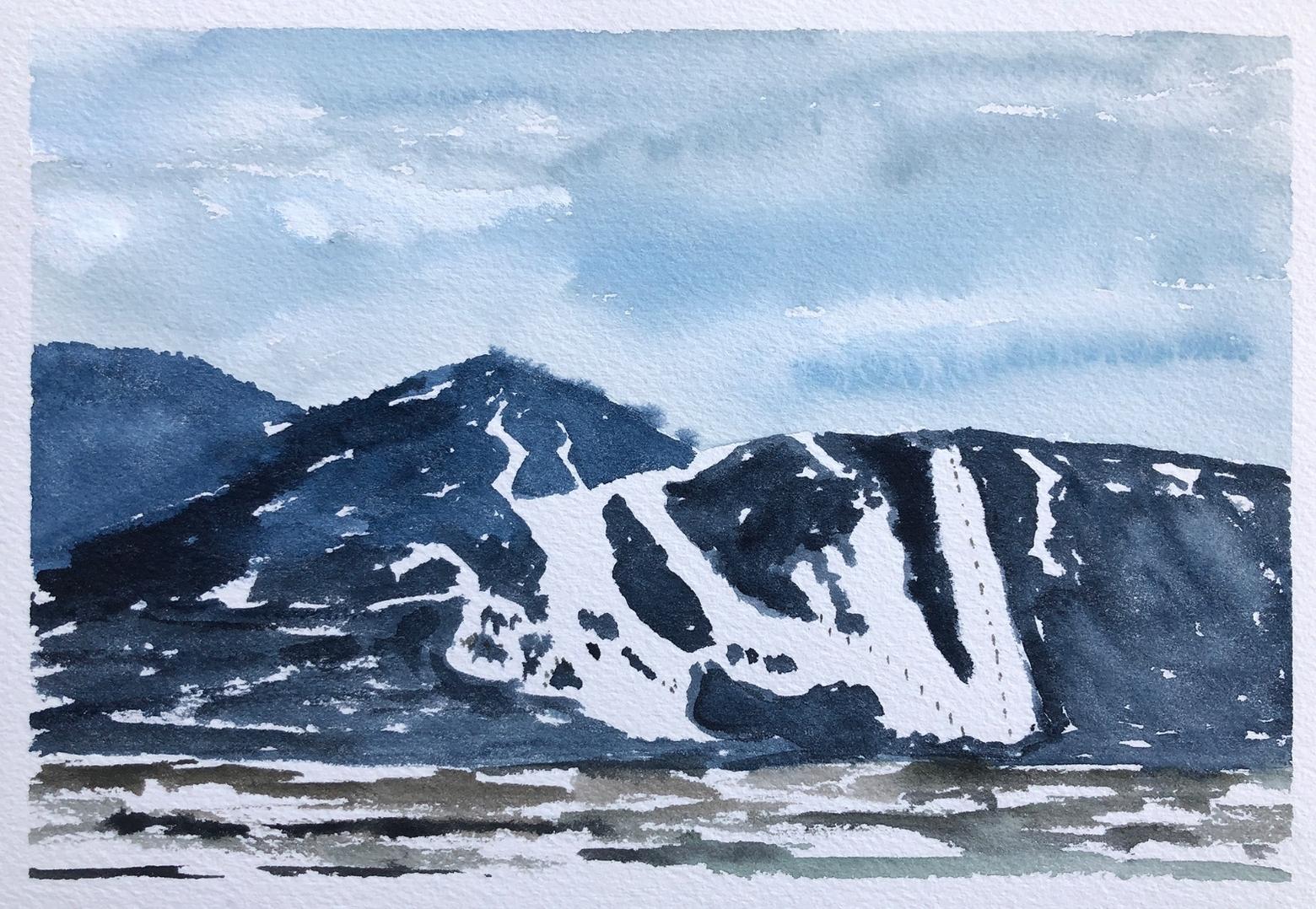

The Future Of The Local Small Town Ski HillSue Cedarholm paints a picture that speaks to both nostalgia and concern about Snow King

Driving in to Jackson Hole from the north the National Elk

Refuge stretches out in front of you. Dangling unmistakably as a backdrop is

Snow King “mountain”, the “town hill.” The snowy white ski runs, cut out of dense

pine forest, create very graphic shapes that can be seen for many miles.

In many ways, the sight announces our winter identity.

Jackson Hole may be best known in modern skiing for the

slopes garlanding the eastern face of the Tetons at Jackson Mountain

Resort. But Snow King marks the historic

beginning of downhill snow sports here.

Locals feel a sense of ownership and belonging, the same that so many

communities do with smaller ski areas that existed before the proliferation of

the massive corporate-theme-park approach to skiing that took root in the

decades after World War II.

Skiers first started hiking the steep slopes of Snow King

and skiing them in the 1920s. No one

traveled into the valley to ski then; roads were often impassable. Locals

strapped long boards to their feet for entertainment during the winter.

In 1926, a ski jump was built. A rope tow was added in 1939

and in 1947 Snow King boasted Wyoming’s first single chairlift. Olympians like current downhill racer Resi

Stiegler practiced and trained on Snow King as a young girl and who knows how

many other greats of American downhill have taken a bombing run there.

Many a Jackson local learned how to carve their first turns

on Snow King. My own children day skiied “the King”; for one reason because it

was convenient and another that it was more affordable—the same attitude that

exists in Bozeman toward Bridger Bowl as a counterpoint to Big Sky and prior to

that the mom and pop place up Bear Canyon.

In my daughters’ younger years we would go to my native

Colorado to ski and they wanted to know where the hard runs were, having

learned to turn fast on the steep, sometimes icy slopes of the King which made

most other groomed trails seem pale.

Today, right before our eyes, the King is being transformed

into a multi-season “working mountain” for those seeking fun, a commanding view

of town or a workout.

In summer months it is peppered with hikers, mountain bikers

and horseback riders. Townies gather there, painting and attempting to talk

while hiking up the nearly vertical trails— solving the world’s problems or perhaps

their own personal dramas along the way.

Just as so many in Bozeman head to the “M” trail or Drinking

Horse, the switchback trails up Snow King make for an easy quick respite.

The once quaint town hill, however, is at a crossroads,

emblematic of what is happening on a much larger scale in Jackson Hole and

other Greater Yellowstone tourism communities.

The path ahead involves addressing the uneasy question of how to

maintain a sustainable private business so central to our identity without

increasing the impact on the town of Jackson and, I would argue, equally as important,

the abundance of wildlife who calls these steep hillsides home.

Mule deer, elk, moose, mountain lions, black bears, even

occasional wolves and grizzlies range through the forested terrain that

includes and encompasses Snow King which is set, after all, on public land.

Snow King’s fate, since it leases land from the federal

government, will be determined by U.S. Forest Service approval for a new

expansion plan and it has left some wondering if the federal government ought

to be responsible for keeping private business viable by enabling it to grow

bigger.

Others have asked about the long-term wisdom of trying to

keep a ski hill viable and enabling its expansion in the face of inevitable climate

change when snow seasons narrow. Still more wonder where we as a community are

headed with expanding outdoor recreation as we convert natural lands into

places for human amusement.

For me, Snow King forces us to think harder about Jackson’s

place in nature and wrestling with the reality of what sets it apart.

The new Snow King investors are proposing to build a new

restaurant on the summit, add a gondola, expand skiable terrain and install a

zip line. In the last few years they

already added the “Cowboy Coaster” thrill ride, mini golf and the Treetop

Adventure ropes course. Not to mention, in late winter, the mountain hosts the

noisy World Championship Snowmobile Hill Climb, which is kind of a super bowl

meets NASCAR for snowmobile high markers.

No one can blame the private owners of Snow King for wanting to expand—scaling up is

the natural progression of a business model—but at what cost? Do we want a

Disneyland-like resort towering over our town on public land?

And yet, what is the alternative? What would happen if it went away? If the Forest Service is going to accommodate

this private enterprise, will it do the same for others? What are the ethics of

that? If it helps to further transform the King into an even more intense

recreation area, at the expense of wildlife, does that mean the Forest Service will offset this

“sacrifice zone” by bolstering protection for other areas dealing with intense

use?

I don’t know of anyone who doesn’t have nostalgia for our

town mountain. How do we modernize yet

keep the status quo? Ski resorts all over the country are looking for ways to expand

summer activities, both to keep their business viable year round and support

private real estate at mountain bases. The Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance, the

local environmental organization founded four decades ago to stop natural gas

drilling just east of town, provides a solid overview of the issues involving

Snow King.

Roller coasters and miniature golf courses exist in a

hundred other places; very few American communities have wildlife like we do at

the edge of town on public land. Do we want to be a town whose evolution is to

become like everywhere else or do we want to remain an exception to anywhere

else?

World Championship Snowmobile Hill Climb at Snow King Mountain

Cowboy Coaster at Snow King Mountain

Ultimately, citizens will have an influential role in telling the Forest Service what we want with this beloved piece of land.

I hope the ad hoc advisory council, formed to deliver recommendations for Snow King’s future, takes a hard honest look at the philosophical questions, the soul-searching ones for our community, that are in play with the expansion proposal.

Meanwhile, we will still skin up in the dark, no headlamp needed, the glow from town giving you just enough light, then make first tracks down, just as the eastern sky becomes light, a new day. We will begin on private land, ascend into public land, and return. We are waiting to see what the new day brings for Snow King.

This is what I’m thinking about as I dab my brush into a pool of watercolor paint.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Below, Resi Stiegler, a member of the 2018 U.S. Olympic women's downhill ski team reflects on her early years skiing at Snow King with her father, Olympic gold medalist Pepi Stiegler.

I hope the ad hoc advisory council, formed to deliver recommendations for Snow King’s future, takes a hard honest look at the philosophical questions, the soul-searching ones for our community, that are in play with the expansion proposal.

Meanwhile, we will still skin up in the dark, no headlamp needed, the glow from town giving you just enough light, then make first tracks down, just as the eastern sky becomes light, a new day. We will begin on private land, ascend into public land, and return. We are waiting to see what the new day brings for Snow King.

This is what I’m thinking about as I dab my brush into a pool of watercolor paint.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Below, Resi Stiegler, a member of the 2018 U.S. Olympic women's downhill ski team reflects on her early years skiing at Snow King with her father, Olympic gold medalist Pepi Stiegler.

Related Stories

February 1, 2018

Are Trump, GOP Fueling A Blue, Green Tidal Wave?

Congressional redistricting and deepening support for conservation could soon be re-shaping the map of America

October 17, 2017

America's National Elk Refuge: A ‘Miasmic Zone Of Life-Threatening Diseases'

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is known internationally for its wildlife. With the arrival of Chronic Wasting Disease looming, the epicenter of...

January 12, 2020

Experts Say The Magna Carta Of American Environmental Law Is Under Siege

Special Report: The National Environmental Policy Act benefits the lives of all Americans every day. So why is the Trump Administration...