Back to StoriesThat Which We Cannot Escape In Life

March 2, 2018

That Which We Cannot Escape In LifeFor psychotherapist Timothy Tate, the minister's son, dealing with death requires making peace with oneself

Suffering: No one in human life escapes its grasp. And yet while it is something we all wish to avoid, it carries forth the most potent meaning.

How

we confront life's fundamental themes is influenced by the personal experiences

we have in their name such as: birth, love, betrayal, children, loss,

separation, joy, beauty, wealth and, invariably, death—each of which can be accompanied by suffering. And these are just a few of the

Shakespearian-level big ones.

We each have different stories woven into us around

these archetypes but the one theme that has come up in my consulting room

lately is death. As two people said to me last week, “I am scared to death of

dying.”

Maybe hopefully sharing with you, Mountain Journal reader, my personal experiences with death

that shaped my perception of its nature will shed light on the gravitas of

death’s sting for the living. Hopefully, it will lend some insight into how I try to help others cope with mortality when we meet behind The Blue Door.

I

was introduced to death at an early age. My father’s mother died in Ireland

when I was five. I remember driving into Chicago’s sole commercial airport at

the time, Midway Field, and watching my stoic yet grieving father walk across

the Tarmac to board the TWA Lockheed Constellation aircraft with its four propellers

spinning and its three tail fins erect and proud.

The

year was 1954. There were curtains in the plane’s cabin windows. Upon his

return Dad said he could see the waves frothing on the Atlantic Ocean while

they bucked the headwinds heading toward Shannon.

I

did not know my grandmother; she was from “the auld sod,” the tough wife of my

grandfather, a drunk Irish horse breaker. Or so the story goes.

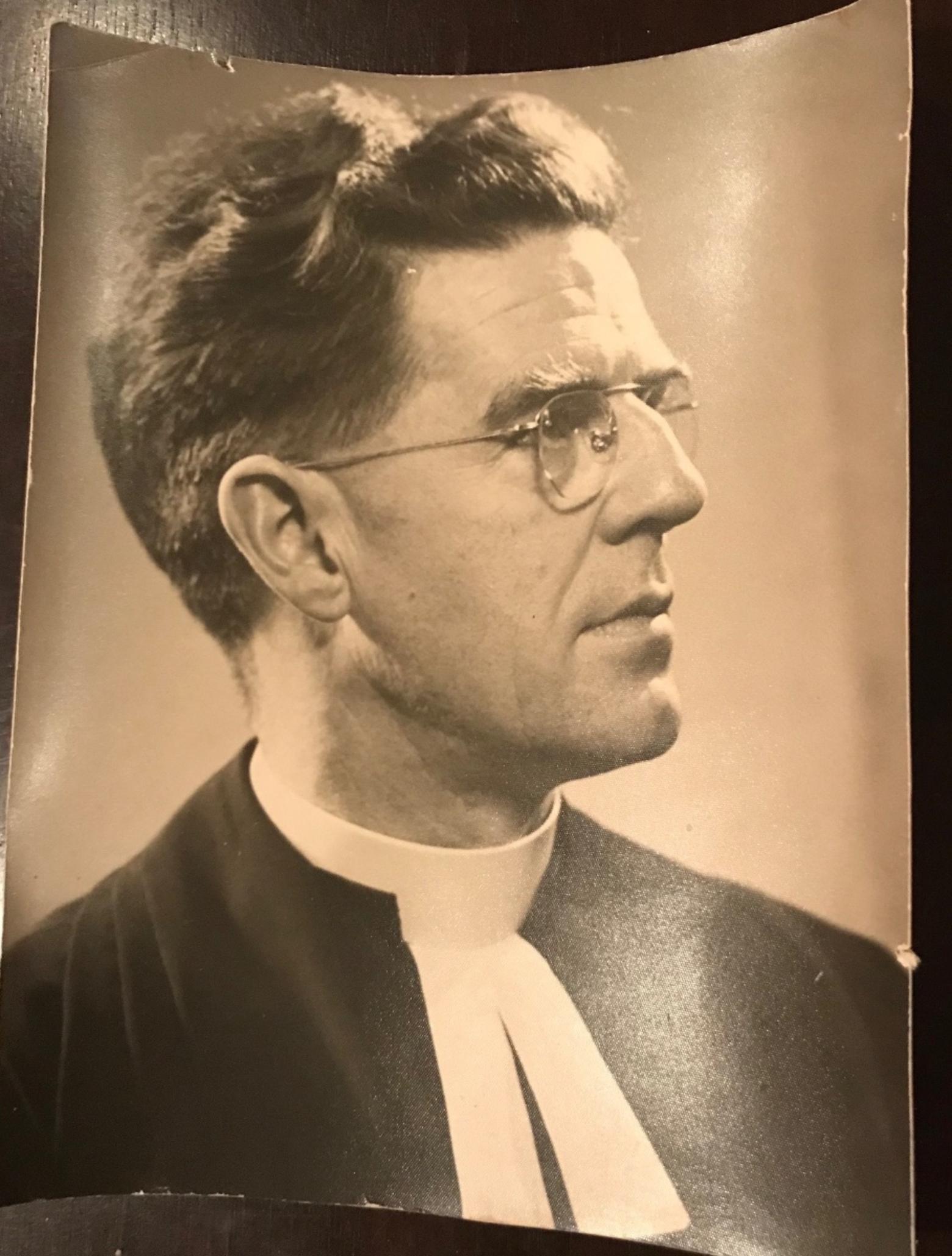

What

I did hear was that death was an unwelcome, unannounced visitor that never left

empty handed. And from my minister father’s pulpit I heard in no uncertain

terms that “Ye, best be on the right side of the Lord when it's time for you to

play tag with the angels.”

The

alternative was eternal damnation. Sunday school and prayer services and

subsequent church services cemented the notion that accepting Jesus as your

personal savior was The Way.

As

an inquisitive child, I asked my mom a question as we stood together in the

kitchen of the manse one Sunday afternoon after the weekly post church roast

beef was eaten and the dishes washed. How did I know when and if I was saved?

And

here’s the thing, my mother, the pastor’s wife, said, “Timmy, you never know.”

This was my virgin existential moment of total despair.

My

mother, father, and I crossed the Atlantic on a steamship in 1956. We took the

train from LaSalle Street station in Chicago on the Grand Trunk Line to

Montreal Canada, where we were scheduled to board the S.S. Great Britain and

sail down the recently opened St. Lawrence Seaway on our voyage across the

North Atlantic to Liverpool, England.

The

immensity of the North Atlantic in June as it surges off the coast of Labrador

both intrigued and terrified the lad of eight that I was. Icebergs were often

visible during the seven day crossing. One iceberg in particular caught my

attention. There was a solitary polar bear pacing around its perimeter as it

drifted in the swells disappearing and reappearing for the time it took our

pitching, creaking ocean liner to pass.

Today,

that iceberg is likely long gone and who knows what awaits the descendants of

that snow-coated ursid.

Once

in England we took a bus tour through Scotland. The glass-domed tour bus held

mostly retired people. My parents then were in their fifties.

The

bliss of all the attention paid to me as a trusting youngster and the sublime

beauty of heather draped hillsides rolling by created a deep feeling of

wellbeing that I can remember to this day. It lasted until we crossed over a

stone span bridge. I looked down into the black tannin water of those Highland

Rivers and saw men running along the bank, one carrying a thick blond colored

rope draped over his head and laying on his heaving chest.

Looking

back to the river I saw a body in a dead man’s float punctuated by my mom’s

urgent voice: “Don’t look at that.”

The

next time I met death’s entourage was at my older brother’s child’s funeral in

a Clarendon Hills, Illinois cemetery on a dank frozen fog afternoon. I was 12

and I did not understand why there were sheets in the trees and scattered

around the parkland surrounding the cemetery. My mom whispered to me that these

sheets were covering the bodies of those people killed in a morning crash of a plane trying to land in a wintry storm at Midway Airport.

Dad

presided over the wee casket at the graveside speaking about “dust to

dust.” I never met Heather, my brother’s

daughter, but I saw in his grief that death’s sting was inconsolable. I

remember thinking how could someone so small be allowed to die?

I’ve

dealt with death—in my practice, in our mountain town community and up close and very

personally. I have lost my sister to cancer as well as her two sons—one to

cancer and one to a fire in his cabin sparked by the negligence of a drunk

smoking man.

I

have presided over funeral services and grieved in fellowship when community

members have passed over.

If

there is a lesson to be learned by those of us who remain after our dear one’s

depart it has to do with fear. As R.D. Laing suggests in his writings, the fear

of dying is actually a fear of fully living. How

else can the end we all face be so intimidating if it were not the ultimate

mirror for a sense of unfulfillment in the way we are choosing to live while

alive? And when one does die there is an eerie shimmering presence of life’s

force leaving.

Witnessing

a person dying is its own moment. There was my dear aunt, Frieda, when I was

32. Her sister, my Mom, died six years

earlier while I was teaching in France. My father’s death then was unknowingly four years in the future, waiting for him in Miles City.

As

the nephew closest to my aunt, I was charged with returning to my mother’s

birthplace, Muskegon, Michigan where Freida lived her life out in their family

home hand built by my maternal grandfather, a Swedish immigrant.

She

was a gifted artist, composing birthday cards for the National Republican

Committee’s birthday wishes to Ike and the like. She lost a lung to leukemia

back in the 1940s giving her a humped

back. She taught me the card game cribbage pegging out 15-1,15-2, on the

screened-in porch during humid Midwest summer evenings. Her piercing

bespectacled eyes would flash at times with unnerving directness.

If

you have spent any time in proximity to an ICU ward you know the mechanical inhale

and puffing exhale of breath sounds emanating from the medical assistance

equipment. It’s a calming desperate sound, regular, rhythmic, and artificial.

Add to that the beeping of beige monitors tracking the critically ill vitals

creating a suite of acceptable best medicine practice. It’s like a zoo but

different, artificial, humane, sacrosanct, where the protected, observed, and

managed life survives in captivity.

I

was alone in the waiting room, institutional carpet and angular wooden frame

chairs walls adorned with bucolic nature scenes or inspirational quotes about

sunrise. Sometimes I find hope of a new day a cliche about gratitude.

My

aunt Frieda was in her last days if not hours now, kept alive by artificial

means. I was the closest family member available and so was charged with making

the fateful decision of whether or not to pull the plug whenever that time

came.

"As Arthur Clarke shares in his book Tales of Ten World's: ''The person one loves never really exists, but is a projection focused through the lens of the mind onto whatever screen it fits with the least distortion.'"

It was clear that when the attending physician

came on his rounds that today was that time. Frieda's frail health was stronger

than any of her siblings but was now at the end of its run. The physician went

through the end of life support protocol and retreated to leave me alone with

my beloved aunt as her life drained away.

There

is an eerie fullness to the emptiness of the dying moment. What is most

striking is that the head, the animated capital of our life’s choices, quickly

and quietly becomes a vacant skull.

The absence of life is peaceful like a barren

landscape is. Death is the ultimate closing act where the life of the person in

question can no longer hold the projections of love or hate or need or judgment

that it has screened for the others. The withdrawal of this intimate other who

has carried our projections is experienced as our loss, our grief. There is no

other conclusion to life than death, the end of the show, the cold snow that follows the rain and eventually melts away.

As

Arthur Clarke shares in his book Tales of

Ten World's: “The person one loves never really exists, but is a projection

focused through the lens of the mind onto whatever screen it fits with the

least distortion.”

The

Tibetan Book of the Dead tells us about the Bardo state, or passageway

between worlds and instructs those

mourning the beloved’s loss to sit by her and whisper into her ear to not be

distracted by the demons of our collective unconscious but continue steadfastly

toward the light. I find this protocol helpful advice for the living since our

fear of death is exactly that, being captured by the demons of our ego’s fear.

In other words, the task of the living is to recall their projections while

alive rather than save them all up for the final crossing.