Back to StoriesHe Set Out For A Long Walk Down Roadkill Highway

October 12, 2020

He Set Out For A Long Walk Down Roadkill HighwayScott Poindexter is crossing the country to raise awareness for wildlife crossings. During a pit stop in Greater Yellowstone he assessed the grim toll

By Todd Wilkinson

"Walking is the great adventure, the first meditation, a practice of heartiness and soul primary to humankind. Walking is the exact balance between spirit and humility."

—Gary Snyder

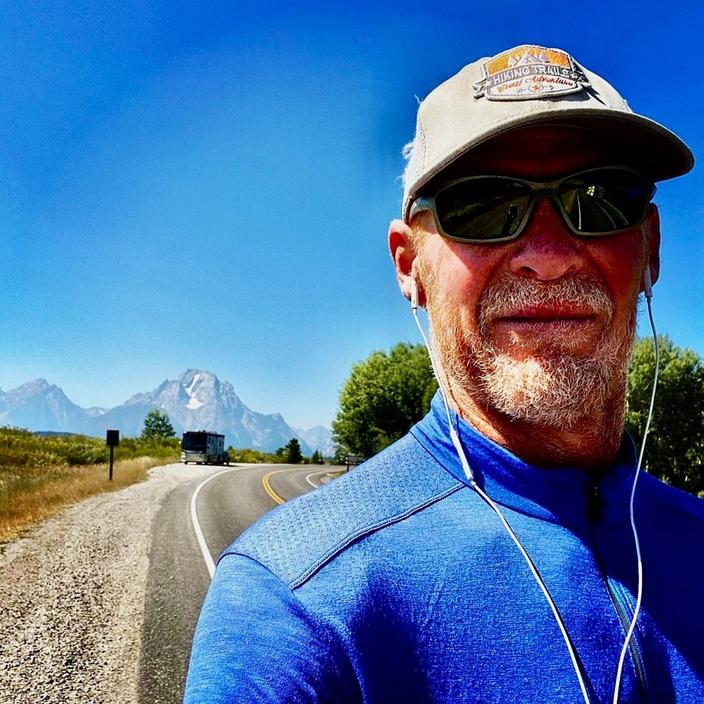

Scott Poindexter isn’t anybody famous. He’s just an average Joe, a chiropractor ironically endowed with some achy joints, trying in middle age to complete a walkabout across roadkill nation.

Poindexter’s quest, just by being out there inconspicuously, is raising awareness about the need for more wildlife underpasses and overpasses in America. He says they could save thousands upon thousands of animals every year and many human lives. His roughly 3,000-mile journey, which commenced in June, is taking him from Washington’s Olympic Peninsula on the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic coastline near Savannah, Georgia.

Is he the first ever to make such a trek in the US? What he’s endeavoring to complete isn’t easy; the tolls exacted by distance on the body are many—as well as witnessing the crushing effects of chrome engine grills, heavy metal bumpers and the smashing force of rubber tires.

Poindexter already has observed a lot of carnage, marking the places where human motorists pass through landscapes often oblivious to animals that are simply aspiring to move across thin strips of asphalt. He is out there, he says, to remember the latter that didn’t make it and have them register with humans.

“I was first introduced to the need for wildlife overpasses in Colorado where the widening human infrastructure of roads continues to carve up wildlife habitat,” he says. “What really opened my eyes was when I volunteered with a conservation group, Rocky Mountain Wild, and we set up cameras along the multi-lanes of I-70 near Vail Pass. I don’t think most people understand just how much our highway system is impeding wildlife movement.”

Poindexter’s cross-the-country path not long ago took him through the heart of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem known globally for its wildlife and where both animal migrations and underpasses and overpasses are a hot topic.

What did he find here? Surprises, that’s what. He spent Labor Day walking Yellowstone’s roads, entering the park at West Yellowstone, then headed to Norris, onto Canyon and southward through Hayden Valley. At one point, he barely missed being there when large male grizzly 791 pursued a wounded bull elk into the Yellowstone River and took it down.

How was it strolling through Yellowstone at one of its busiest times and during a month that became the most visited September in the history of the 148-year-old park? Poindexter had been to Yellowstone before as a regular tourist but never navigated it wholly as a pedestrian.

“I must say it was a letdown, kind of horrible, actually, when you are forced to consider the park from the wildlife perspective,” he said.

For a nature preserve so heralded for its animals, he can’t imagine how intense traffic loads on park highways are not having a deleterious impact on wildlife movements.

“It’s kind of shocking when you experience wildlife jams in Yellowstone on foot,” he explained, noting that while motorist attention is usually focused on a few visible roadside animals, he wonders how other creatures, unseen, are being impacted. In 2018, drivers collided with—and killed—at least 76 large mammals in the park and that’s only what rangers know of.

Many remember that in summer 2016 one of the cubs of Jackson Hole Grizzly 399—a bear nicknamed "Snowie"—was struck and killed in a hit and run accident in Grand Teton National Park and other bruins have been hit by vehicles too.

On every stretch of his route across multiple states, Poindexter has encountered animal carcasses several feet off the roadbed where they were struck, mortally wounded and then hobbled into brush to die. Some of the casualties would have been sight unseen to him, too, but the odor of their decomposition sent him foul whiffs.

It’s no mystery why wildlife watching in Yellowstone tends to be best during crepuscular hours of the day—dusk and dawn—when the human bustle is low and has quieted down. Further, there’s a reason why crepuscular hours, statistically speaking, tend to be the most dangerous for motorists, especially evening around sunset when light glare can be blinding.

For the last 20 years, Poindexter has lived in Colorado and seen the impact of development on wildlife habitat as development in that state ballooned. Besides being a chiropractor, he has traveled across Africa and Asia on a motorcycle, and rode his bicycle across the US. He also has been a tour guide taking clients into the Colorado Rockies.

Earlier this year, as the pandemic arrived, he wanted to do something really different.

In a way, this solo trip has turned him into something of a citizen scientist gathering random datapoints in space and time along a linear transect. While it’s not comprehensive or precise, it does offer insight. And he's reaching people even though he's not in the limelight.

Poindexter has an unslick website where people can follow this project and adventures at BoldlyExplore.com that exists to educate readers about why erecting wildlife crossings are important.

“I am seeing things I never did before when I was behind the wheel. I’m appreciating the kind of country that exists on both sides of the highway,” he says. Most people think of trips as carrying them between points A and B, always forward-looking through a horizontal sideways blur. They don’t realize that they’re only getting a narrow perspective of habitat, he explains.

Early on, a heavy backpack was putting a strain on his hips and knees. Switching to pushing a three-wheeled kid stroller with all-terrain tires gave him the upgrade he needed. He has no support vehicle trailing him or setting up forward camps. He’s already into his fourth pair of shoes. Unlike adventure athletes partaking in backcountry expeditions, he doesn’t have any lucrative sponsorships from big outdoor recreation gear companies either or even a conservation organization backing him.

Doing this on a shoestring budget, he continues to receive modest donations through gofundme which have helped him pay for rare lodging in motels or extra food.

What he’s discovered, staying mostly in developed and dispersed public land campsites, is that people in this covid year have been generous of spirit.

"I would say 98 percent of the folks I’m interacted with are just good people doing what they need to do to survive—to feed themselves and spend quality time with their families. They are interested in what I've discovered,” he said. “We have an amazingly beautiful country, especially in the West, but it’s in peril unless we get conversations going about growth and destruction of high value natural areas.”

As Poindexter descended through Yellowstone and moved southeasterly along Togwotee Pass and across the Wind River Reservation, he hoped to catch a glimpse of the Great Bear but no such luck.

Suffice it to day, he’s seen enough (dead) native four-legged members of the animal kingdom, plus pets, and livestock to assemble quite a check list. With each new day, taking on another 20 to 25 miles, the dozens of roadkills he’s counted quickly turned to hundreds, and now thousands.

“It’s a disaster in some places and it’s been shocking to me how fast vehicles fly by through places that you know have a lot of wildlife,” he said. His adrenalin surges when he’s seen animals foraging just off the highway, hidden from motorists’ view, and then the animal, sometimes a mother with young offspring, prepare to dart across.

Helpless, he prays they won’t venture into danger, but there’s nothing he can do. He’s been an eye-witness to both close calls and grim, heartbreaking collisions.

I asked Poindexter if being exposed to the accumulating tally has left him traumatized? Yes, he said, more than he thought. What’s most gut-wrenching, he noted is seeing all of the kinds of incredibly beautiful and amazing life forms that have lost their lives. Large mammals. Small mammals. Birds. Reptiles. Amphibians.

In a strangely macabre way, there’s a little bit of Jack Kerouac’s adventurous On the Road spirit in Poindexter’s Aristotelian course—heightened by the fact that Kerouac too liked having contact with nature. The beatnik poet and writer spent part of a summer manning a fire lookout tower on Desolation Peak in Washington State. He later centered his novel The Dharma Bums on protagonists who hiked and hitchhiked their way across the West. Notably, the character Japhy Ryder is based on nature poet and essayist Gary Snyder.

Poindexter is approaching his epic navigation with no pretension that it will result in anything profound—other than he hopes motorists will slow down and actually pay attention when they see those wildlife crossing signs on the road. He is compiling a list, identifying some of the death zones he’s seen, where maybe it might be wise for highway departments to consider installing wildlife over- or underpass.

Will they listen? He doesn’t know.

Still, his cause is a worthy one. Roadkill is a product of the modern age. It did not exist much before the automobile’s invention or prior to high-speed rail. One set of statistics estimates there are 250,000 animal-vehicle accidents and maybe one million animal casualties with a few hundred human deaths each year.

Given varying economic assessments of the value of a human life established in court cases, saving just one or two human lives a year validates the construction of wildlife overpasses and underpasses. And this doesn’t even take into account how they can enable the ecological process of seasonal terrestrial migration to continue which keeps wildlife migrations more resilient.

Reed Noss, the eminent conservation biologist who has provided a number of ecological analyses of Greater Yellowstone and beyond, says there is not a single decision made by humans that holds larger implications for nature in given areas than building a road.

Reed Noss, the eminent conservation biologist who has provided a number of ecological analyses of Greater Yellowstone and beyond, says there is not a single decision made by humans that holds larger implications for nature in given areas than building a road. Roads often beget more development which can result in bigger, improved roads that increase speeds.

Wild country has been lost, fractured and degraded because of thoughtless road design, construction and routing, he says. And, by extension, Ross and other colleagues say that any pathways that push significant amounts of people through landscapes negatively impact wildlife.

Poindexter doesn’t have a megaphone and he hasn’t been invited to appear on one of the national morning TV talk shows yet. But he’s trying to do his part for wildlife. “My dream is to create a tribe of people, who want to get off the couch and explore more instead of watching a screen. And along the way make a difference for wildlife and nature preservation,” he says. “The greatest life changes happen when you get outside your comfort zone. Important discoveries within only rise up when you confront difficulty.”

How can a citizen make a difference? Poindexter says “just get out there and do something that you hope will contribute to greater public awareness. I’m just trying to share the stories of what I see being out on the road, understanding what’s going on there mile by mile. You see so much more stuff, so much more beauty, so much more wildlife, when you go slow.”

What other message would he like to impart? “Think beyond yourself, think generations from now and what you will leave them. Think about how freely you move around with your car and how that freedom has cost wildlife and for some animals trying to exist, created pure hell.”