Back to StoriesWide Awake In The Land Of Griz

July 15, 2018

Wide Awake In The Land Of GrizSteve Primm in part 2 of his MoJo series asks, 'Are you really ready to explore bear country?'

In my last column—Encounter With Grizzly—Part 1: The Shooting—we discussed in general terms the need to be adequately prepared to venture into grizzly country. That piece was prompted by a deadly grizzly-human encounter in Wyoming’s Wind River Mountains that left a mother grizzly dead and her orphaned cubs-of-the-year likely doomed.

In the time it took to write and post that column, the northern Rockies racked up more dust-ups between our species and Ursus arctos. It was an unsurprising stew: grizzlies euthanized for eating garbage and garden vegetables, grizzlies too close to livestock, and so on. And in west-central Alberta, a noteworthy non-lethal stand-off between a grizzly family and a pair of ultra-marathoners.

That incident with trail runners – in the rugged country north of Canada’s Jasper National Park – is yet another lesson-rich story. A group of 14 runners set off, training for the unfelicitously-named Canadian Death Race. Two strong harriers had outpaced the rest and were making good time as they forged uphill along a trail thick with alders. At a range of about 20 yards, a grizzly poked her head out of the brush. One of the runners immediately readied his bear spray, just as the grizzly charged.

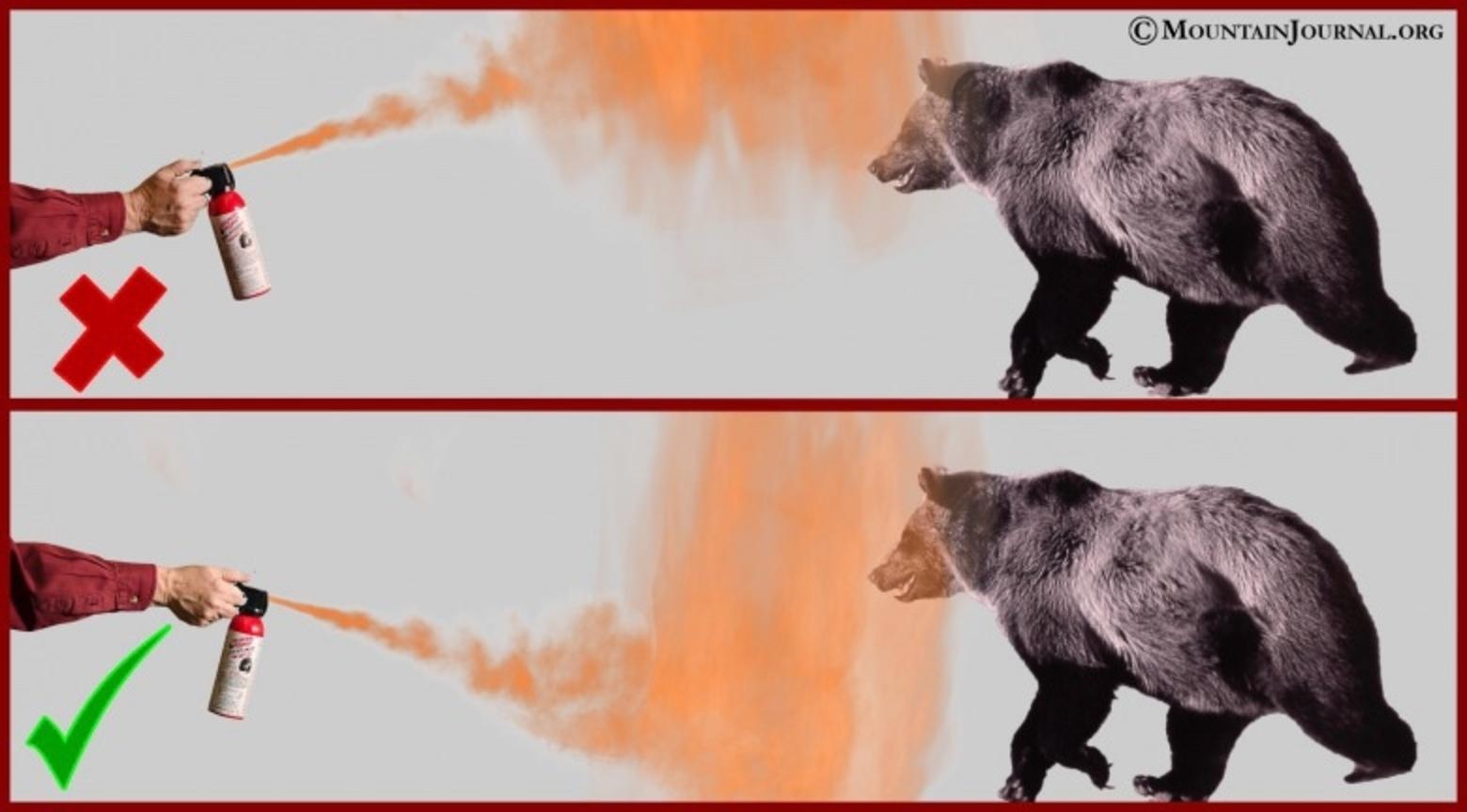

To review the arithmetic from my last column: a charging grizzly can cover about 15 yards per second. A proficient bear spray user will typically need two to three seconds to access and fire their bear spray. You’ll get the best results (i.e. no injuries) if the bear meets your spray cloud some distance from you; you need a fraction of a second for the bear spray to affect the bear, and ideally there will be space enough for the bear to stop or change course before colliding with you.

In the Alberta incident, the runner was able to fire the spray at a range of under two yards when the charging bear was scarcely more than a tenth of second away. Maybe because of the bear spray’s scorching hot capsaicin, maybe because of its startling high-pressure hiss, maybe because of the big orange cloud, the grizzly veered around the two runners.

As if things couldn’t get more riveting, the grizzly’s two cubs then emerged from the brush, putting the runners between mother and offspring. A short fracas ensued. We know it was under two minutes because the man was wearing a device that recorded pace and his red-lined heart-rate before the grizzly family made a quick exit back into the brush. Neither runner sustained injuries, although one did get knocked down briefly.

As if things couldn’t get more riveting, the grizzly’s two cubs then emerged from the brush, putting the runners between mother and offspring. A short fracas ensued.

The runners did some things right, such as carrying bear spray and obviously being prepared to use it. There are some glaringly obvious wrong things about this incident, too —namely, why is a 1,000 runner ultramarathon routed through high quality grizzly habitat?

On a more granular level, this encounter underscores the importance of maintaining situational awareness in grizzly country. Broadly, situational awareness means paying attention to what’s going around you. In bear habitat, there are specific things to focus on to reduce your risk of a close-range encounter. It begins with trip planning: where am I going, and could there be bears there? It also involves asking if are bears likely to be right there now? For example, are they in a wild berry patch or in spring might they be on a carcass or during fall on a carcass or gut pile?

The Alberta runners shared a photo of the incident site with the CBC. There is dense vegetation, and a slight uphill grade. Tacticians would call it a short sight line— the kind of place where you can’t see very far. The photo looks strikingly similar to photos I use in bear safety presentations, illustrating the very kind of setting where you need to slow way down and make plenty of noise. Notice those sight lines—pay attention to what kind of terrain and habitat you’re moving through: how far can I see ahead of me? Is the terrain flat and open, or steep and wooded?

Also pay attention to possible food sources for bears and be alert for signs of recent foraging. Yellowstone National Park bear biologist Kerry Guntherand colleagues have documented 266 species of plants, animals, and fungi that grizzlies feed on; the majority of that menu is plants (175) and invertebrates (37).

There’s no need to learn nearly all of those 266 species. Tune into broad patterns instead. For example, early emergent green vegetation in the spring is a key food for bears just out of the den. When grasses are young and tender, bears can actually digest them, unlike older, more fibrous grass. Berries typically won’t be available until late summer.

Another key food source—although greatly diminished by beetle epidemics and a non-native fungus—is whitebark pine seeds. Whitebark pines are most abundant above 8,000 feet elevation. During a good year for seeds, grizzlies will forage in these forests from early September until denning, but they may be there any time after spring snowmelt.

Learn to look for the sometimes-subtle sign that grizzlies leave behind. Not all grizzly diggings look like they were done with a backhoe; when digging for biscuit root on gravelly slopes, the digs look like shallow bowls instead of trench work. Watch for rocks that bears have flipped in their quest for insects or worms – the vegetation under the disturbed rock should tell you how recently the bear was there.

In thick, dark woods, there may not be much that bears would be eating, but bears like to nap in these shady places during the day.

If you’re in a place where you think you could bump into a bear, make plenty of noise, and slow your pace. If you can’t see very far (less than 100 yards) and you think there could be a bear nearby, it might be a good time to go ahead and have your bear spray in hand.

Even in relatively open country, grizzlies can stay out of sight without even trying. Gullies, swales, or tall sagebrush can obscure a bear from view. Many people think grizzlies would be completely obvious, but that’s not always the case. Here in Greater Yellowstone, our grizzlies tend to be on the smaller side. Adult female grizzlies in Yellowstone average about 35” high at the hump when on all fours. Scan ahead, ideally with binoculars, and have a realistic search image in mind.

Wind is another key factor to tune in to. Bears are heavily reliant on their sense of smell, and they’ll often go out of their way to avoid people if they can smell them coming. I’ve had numerous grizzly encounters in which the wind was carrying my scent slightly away from a bear; once the bear had moved directly downwind and could smell me, it hastily left the area.

Environmental noise – such as wind, rain, or rushing water – will make it harder for a bear to hear you coming. Investigators cited wind and water noise as contributing factors in the recent severe mauling a of bear researcher in the Cabinet Mountains of northwest Montana. The researcher accidentally walked to within four yards of the grizzly; she was able to use bear spray to end the attack.

One wild card is large animal carcasses on the landscape. A dead moose, elk, or deer (or, in some places, domestic livestock) is a major food resource for a bear, and a bear will fight to keep it from perceived competitors. They’re unlikely to move away from a carcass just because they heard or smelled you coming.

While carcasses might be more plentiful in spring and fall, they can obviously be wherever and whenever that an animal happens to die. Be alert for the awful smell of rotting meat. From a safer distance, be alert for the raucous chatter of scavenger birds like magpies, ravens, and crows. It’s fairly rare that a carcass doesn’t have these garrulous heralds perched nearby. Watch for other scavengers, too—coyotes, eagles.

A very large carcass, such as a bison or a horse, could feed several bears for a few days. If you start encountering lots of dark, fouling smelling bear scats, stop and evaluate your surroundings. Look and listen for scavengers, and listen especially for any growls, huffs, or teeth snapping that a bear may using to warn you away. Take heed, and give that carcass a wide berth (200 yards plus). If it’s not feasible to detour around the bear, consider going back the way you came.

If you’re carefully attuned to your surroundings and alert for the possibility of a close-range grizzly encounter, you can take steps to keep those encounters from happening. Slowing down, making adequate noise, and possibly changing course to avoid a bear can keep you from having to face a surprised, defensive grizzly. Of course, making your presence known and obvious is antithetical to the techniques hunters use in the spring and fall.

Grizzly bears are the way that hundreds of thousands of years of evolution made them. They are inquisitive, resourceful, strong, and resilient. And they also respond to perceived threats with ferocious bursts of aggression. We can and should do a better job of avoiding encounters with them.

Sometimes, things won’t go in our favor, and that’s when you’ll need bear spray, and the knowledge to use it. We’ll take that up in the next column.

Far from being a tedious chore, learning more about the ways bears use the land is a way to deepen our connection to place, and to the amazing beings that we share it with. Take off those headphones, slow down, and engage with all of your sensual awareness turned on.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Read also Mountain Journal's story: To Live Or Die In Bear Country: Counting The Seconds In Your Grizzly Moment Of Truth.

Related Stories

November 1, 2017

When An Off-Duty Game Warden Kills A Grizzly

After a mother grizzly with three cubs is shot in Wyoming, critics wonder why the person, who invoked self-defense, didn't use...

January 6, 2019

Grizzly Matters: A Recap Of Court Actions Involving Greater Yellowstone Bears

When it comes to true recovery for America's most famous bruins, the focus is not on numbers but biological connectivity

September 12, 2017

Of Bias And Bears: Is Delisting Greater Yellowstone's Grizzlies Based On Science Or Politics?

For several decades, Jesse Logan gained renown as a forest ecologist. He says the scientific rationale behind removing bears from federal...