Back to StoriesWill Road "Improvement" Harm A Beloved Corner Of Yellowstone?

This autumn, I drove to Cave Falls and the Bechler entrance to Yellowstone National Park to enjoy a day hike along the Fall and Bechler rivers—a hike amid the splendid autumn colors.

October 26, 2020

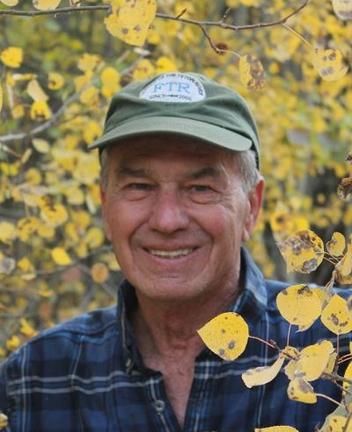

Will Road "Improvement" Harm A Beloved Corner Of Yellowstone?The Forest Service is upgrading a bumpy old dirt road leading to Yellowstone's magical Bechler. Ecologist Earle Layser says that's not a good thing

EDITOR'S NOTE: Mountain Journal exists to celebrate and educate our readers about the importance of Greater Yellowstone in the world, but we do not believe the region's special places need more promotion; rather, they need more informed advocates of farsighted stewardship. A few years ago, the science chief of Yellowstone National Park said the demise of wildness in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem could happen not just via "death by 1000 cuts" but more subtly via "injury by 10,000 scratches." In the piece below, writer Earle Layser of Alta, Wyoming calls attention to one of those scratches that could have lasting negative consequences for a special corner of Yellowstone and a remote area north of the Teton Range along the Wyoming-Idaho border managed by the US Forest Service.

by Earle Layser

This autumn, I drove to Cave Falls and the Bechler entrance to Yellowstone National Park to enjoy a day hike along the Fall and Bechler rivers—a hike amid the splendid autumn colors.

The Bechler has always been a very special place for me. Located in the southwest corner of Yellowstone, it is renowned for its tremendous waterfalls and sparkling clear rivers. In the 1920s, Yellowstone Superintendent, Horace Albright named the water ballet occurring there “Cascade Corner.”

The second and third highest waterfalls in all of Yellowstone are found there, and literally dozens of others. The general area and river is named after Lt. Gustavus Bechler, from when the U.S. Army administered Yellowstone.

But, this time, I found myself horrified to discover that a roughly 12-mile portion of the access road crossing the Caribou-Targhee National Forest in route to the Bechler trailhead was being "upgraded," an anodyne-sounding word that really means it's being excessively widened and coated with crushed gravel surfacing.

But, this time, I found myself horrified to discover that a roughly 12-mile portion of the access road crossing the Caribou-Targhee National Forest in route to the Bechler trailhead was being "upgraded," an anodyne-sounding word that really means it's being excessively widened and coated with crushed gravel surfacing.

Everywhere we turn these days conservation organizations and government agencies are boasting about how they are improving public access to public lands, so that more citizens can "use" natural resources. Yet after the covid-related crowds we've seen this year—and grimaced at—is anyone reflecting on what the consequences of that will be for wildlife and places we treasure for being remote?

The Forest Service, by upgrading the road, is doing something that is certain to have negative unintended consequences for a much beloved area in America's first national park.

The old Forest Service road had been chokingly dusty with volcanic ash, washboarded, and full of chuckholes. But the condition had contributed nicely to keeping the general visitation numbers to the southwest corner of Yellowstone low.

This part of the park has little to no infrastructure to handle increased visitation. There are few existing facilities and the National Park Service currently limits the number of backcountry permits to protect the user experience and resources. Conversely, on the nearby national forest several miles back down the road, groups of ORV and 4x4 vehicles churn up and down the mountainside on a 4x4 “road” they pioneered, without Forest Service authorization or approval, into Sheep Falls.

Worth noting is that, in addition to this backroad improvement, another 12 miles of road beginning in Ashton, Idaho and leading to the national forest boundary has already been paved.

I didn’t recall hearing anything about this Forest Service road improvement project beforehand? It is undoubtedly one of those projects that sat “on the shelf” for years waiting to be dusted off when funding came along. Therefore, local forest leaders probably didn’t feel it necessary to inform the public. It was probably planned a long time ago, part of the forest engineer’s “programmatic road plan.”

If that's the case and in the wake of larger numbers of people descending on our public lands, shouldn't the decision have been re-visited with more overt attempts to get public comment? Do we in Greater Yellowstone want all of our roads leading to backcountry trailheads to make it easier for masses of people to reach, or does the less than fully "improved" condition help to protect such rare isolated places?

The old Forest Service road had been chokingly dusty with volcanic ash, washboarded, and full of chuckholes. But the condition had contributed nicely to keeping the general visitation numbers to the southwest corner of Yellowstone low.

The old Forest Service road had been chokingly dusty with volcanic ash, washboarded, and full of chuckholes. But the condition had contributed nicely to keeping the general visitation numbers to the southwest corner of Yellowstone low.

The general public, which wants everything easy, was put off by the thought of having to navigate a rough road. As a consequence, the Bechler was an out-of-the-way, off-the-beaten path place, where, over the years, you could visit Yellowstone and generally encounter relatively few people. It stood in stark contrast to the scenes experienced along Yellowstone's internal figure-8 highway system in the middle of the park.

The historic Bechler Ranger Station lying at the end of the road dates back 1911. It was built to administer this remote and distant part of the park, primarily to address rampant wildlife poaching and market hunting occurring there. The superintendent, at the time, referred to the local area as part of “a rat nest of poachers.”

In addition, the Bechler was targeted for a major dam.

Today, there is still not even a developed or paved parking area at the station. The road goes on a few miles to Cave Falls, where there is a trailhead, toilet, a few picnic tables, and day parking for a very few vehicles; that’s it.

Today, there is still not even a developed or paved parking area at the station. The road goes on a few miles to Cave Falls, where there is a trailhead, toilet, a few picnic tables, and day parking for a very few vehicles; that’s it.

This part of the park has little to no infrastructure to handle increased visitation. There are few existing facilities and the National Park Service currently limits the number of backcountry permits to protect the user experience and resources. Conversely, on the nearby national forest several miles back down the road, groups of ORV and 4x4 vehicles churn up and down the mountainside on a 4x4 “road” they pioneered, without Forest Service authorization or approval, into Sheep Falls.

And there is a mostly unmaintained campground and the usual dispersed everywhere camping. I grieve because it does not give me much confidence in the Forest Service's ability to protect natural features and ground adjacent to Yellowstone if user numbers are further increased. It saddens me because I once worked for the Forest Service.

The Bechler region of America's first national park has always been administered for backcountry uses by permit only--- horse packers and backpackers or day use hikers, horseback riders and fisherman. It does not need improved road access delivering more users.

The road upgrading undoubtedly is an to attempt to increase Ashton, Idaho’s economic benefit from this part of the park by increasing visitation via improved access. But it is a rerun of what we have observed all over the West over the years: a unique backcountry area, where access is improved to accommodate or encourage more use. This then creates insatiable use that leads to increased use which justifies more improvements and more use permits. It feeds on itself and, in the end, it destroys and forever alters the very essence of the place.

History records that local Idaho communities have in the past sought to derive inappropriate economic benefits from this part of Yellowstone's resources---from market hunting and destruction of some of the park’s last bison, to Idaho irrigation interests proposing a dam in 1919, which was only narrowly averted and that would have flooded the entire Bechler region of the park.

(Read more about that dramatic episode in an excerpt from John Taliaferro's acclaimed and award-winning book, Grinnell, that appeared in Mountain Journal).

Now, what appears to be setting up is the potential for a straight-shot paved road from downtown Ashton, feeding into the southwest corner of Yellowstone. What has made it special could be transformed forever by the thoughtless pursuit of "improvement" and "progress."