Back to StoriesPutting the Heat on Charismatic Microfauna

May 12, 2025

Putting the Heat on Charismatic MicrofaunaA Yellowstone beetle’s secret for withstanding scalding thermal pools could revolutionize human insulation

by Robert Chaney

A chance to see predators in action draws many visitors to Yellowstone National Park. One of the most remarkable, and most dangerous to observe, is also one of the tiniest.

The tiger beetle, Cicindelidia haemorhagica, first astounded scientists in 1891 when early Yellowstone explorers recorded seeing them near Mammoth Hot Springs. The wonder came from the fact the fingertip-wide beetles thrived on thermal soils hotter than what any other known insect could survive.

About 130 years later, researchers with state-of-the-art electron microscopes are close to understanding the beetles’ badassery. And what started as one more curiosity in the massive stack of puzzles propelling the science of entomology may unveil new designs for heat shields that could improve everything from ski jackets to spaceships.

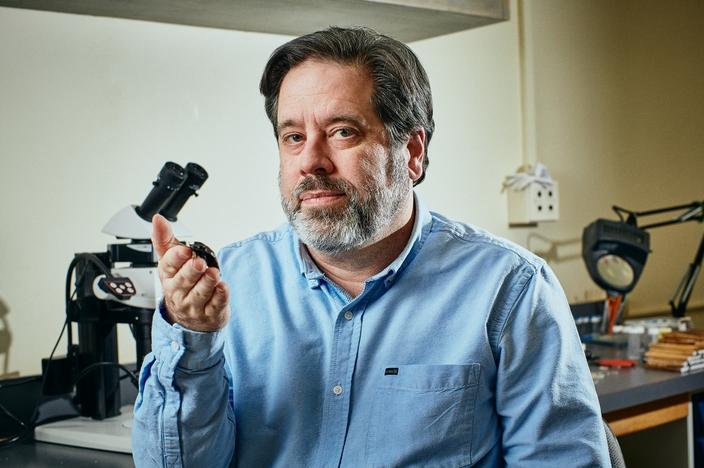

“There are so many knock-on benefits to fundamental research that can help humanity,” said Bob Peterson, professor of entomology and head of Montana State University’s Department of Land Resources and Environmental Sciences. “By studying things living on the extremes and understanding how they live and their biology, we learn more about ourselves.”

After that first 19th-century observation, Yellowstone tiger beetles carried on in relative obscurity until 2006, when Peterson’s mentor, University of Nebraska entomologist Leon Higley, came to Bozeman for a surprise party celebrating Peterson’s promotion to tenured professor. After the festivities, Higley took a drive south to Yellowstone Park.

The wonder came from the fact the fingertip-wide beetles thrived on thermal soils hotter than what any other known insect could survive.

“While I was looking at the hot springs, I saw these beetles and noticed something wasn’t right,” Higley said. “The water was way too hot for the beetles to be there. But they didn’t seem to care. They didn’t show the usual behaviors for cooling themselves.”

Insects can’t regulate their own body temperatures like humans and other warm-blooded creatures can. Instead, most use physical tactics to keep themselves at a comfortable, functional temperature. Common tiger beetles seek shade during the day, dip their abdomens in water to cool off, and maneuver their bodies to reduce sun exposure. Those who know where to look can find tiger beetles in salt flats along the Snake River across southern Idaho, chilling like typical insects.

The Yellowstone beetles blow off all of that. They not only like places with no shade, they forage on soils and pools hot enough to sterilize the reproductive organs of other insects. They’re regularly seen skittering about in 120-degree F water — the same temperature residential hot water heaters usually produce straight out of the tank. Most people find water hotter than 106 F too painful to bear.

And they aren’t just heat-loving “thermophiles.” They inhabit places above 8,000 feet in elevation, where the daily and seasonal temperature swings are dramatic. The ponds they prefer aren’t just scalding, but loaded with caustic acids and toxic heavy metals that have melted the soles off the boots of Peterson’s lab students. It qualifies this group of tiger beetles as “extremophiles.”

It also provides some survival advantages. Among the handful of other things living in those hot pools are mats of bacteria and algae. A few species of flies feed on those single-celled organisms. A few bigger bugs eat the flies. And the tiger beetles hunt those bigger bugs.

“They’re like the wolves of the thermal pools — the top predator of insects that live there,” Higley said. They also scavenge insects and spiders that are stunned by the steam heat when flying or floating above the pools. And hardly any other creatures are heat-tolerant enough to hunt the beetles.

In 2022, someone fell into the Abyss Pool in the Yellowstone's West Thumb Geyser Basin. All park employees recovered was part of his foot in his shoe.

What’s more fascinating? Tiger beetles move so fast when they hunt, they go blind. Their eyes can’t take in enough light to form an image, so they move in a distinctive run-stop-run pattern to reacquire an image at every pause.

In some ways, researching tiger beetles can be more dangerous than studying grizzly bears. Getting close enough to observe them means venturing into thermal areas where the soil may not be strong enough to support a scientist’s weight. Breaking through the crust could lead to drowning or life-threatening burns from the scalding water. In 2022, someone fell into the Abyss Pool in the West Thumb Geyser Basin. All park employees recovered was part of his foot in his shoe.

“I didn’t realize it’s a generally active volcanic area,” Higley said of his early observations. “Locations aren’t constant. Springs move. One research site we set up moved 20 meters in about a month.”

It took 10 years after Higley’s reacquaintance with the unexplained questions of Yellowstone’s tiger beetles that Peterson was able to gather the funding and graduate students to start pursuing answers. Study teams deployed in threesomes: one to watch the beetles, one to measure temperatures, and one to watch for grizzly bears. After they confirmed what the insects could do, the researchers shifted their focus to how.

Those answers are beginning to form across the MSU campus in the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering. Peterson’s entomologists collaborated with assistant professor of engineering Chelsea Heveran to image tiger beetle exoskeletons with electron scanning microscopes.

“These tools will let you take a very small specimen and zoom in to thousands or even hundreds of thousands of times in magnification and see what it looks like,” Heveran told the MSU News Service in April. “It’s the same technology that would let you see the texture on a human hair, or let you see little tiny holes in bone.”

Peterson suspects something about the nanostructure of a tiger beetle’s abdomen plates somehow reflects or diffuses infrared heat. They may also have heat shock proteins in their internal organs that allow them to function at extreme temperatures. And the beetles lay their eggs in very hot soils, meaning their larva also have unexplored thermal tolerance. Those questions have barely begun to get attention.

“By studying things living on the extremes and understanding how they live and their biology, we learn more about ourselves.” – Bob Peterson, Head of Land Resources and Environmental Sciences, Montana State University

“Relatively speaking, we know a lot about the bacteria, algae, archaeans and other single-cell organisms in thermal areas,” Peterson said. “We don’t know much about multi-cell animals like insects. But life finds a way to thrive in extreme environments.”

The Yellowstone tiger beetles have such different capabilities from tiger beetles south of Boise, Idaho, that it’s worth checking if they are a separate species. That could be done with a polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, test that teases apart DNA genetic sequences for identification. The only barrier is money. While funding for more charismatic megafauna like wolves and bison is prevalent, Higley said, bug studies “tend to run on shoestring budgets.”

“There’s precedent for amazing, important, practical things coming out of basic research,” Higley said. “The entire molecular biology revolution is dependent on an enzyme they found in Yellowstone in a single pool. Without that, we couldn’t do PCR.”

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Mountain Journal is a nonprofit, public-interest journalism organization dedicated to covering the wildlife and wild lands of Greater Yellowstone. We take pride in our work, yet to keep bold, independent journalism free, we need the support of readers like you. Thank you.

Related Stories

February 20, 2024

As Wildfire Season Looms, Firefighters Battle Low Pay and Low Snow

The

Wildland Firefighter Paycheck Protection Act could permanently raise federal

firefighter salaries. But even if Congress can pass it, the proposed

legislation still isn’t...

March 3, 2025

Elk in Crazy Mountains Test Negative for Brucellosis, Easing Livestock Concerns

Agency and

state officials complete latest surveillance effort in Montana's ongoing battle

against wildlife-livestock disease.

August 6, 2024

Yellowstone Bison Plan Looks to Balance Interests

While

conservation groups have largely praised the new plan to govern bison

populations within Yellowstone, Montana’s governor and its ag community are

concerned about...