Back to StoriesWhen The Government Tries To Think Big

March 29, 2020

When The Government Tries To Think BigThirty years ago, Greater Yellowstone's first attempt at having a grand vision to protect the ecosystem turned into a whimper. What happened? A first-hand account from a civil servant who was there

I read in Mountain Journal recently that there has been no vision for Greater Yellowstone championed by government civil servants that lays out where this public-land rich region will be in another human generation.

It's true. It hasn't happened for a number of reasons that go beyond the short-term tenures of those in charge. The statement struck a nerve. I was there 30 years ago, as a civil servant involved with trying to craft the first iteration of a grand vision and watched the disintegration of the effort happen.

The initiative was led by the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee comprised of superintendents of the two national parks and supervisors of several national forests. The GYCC has been around since the mid-1960s, far exceeding any individual member’s tenure. I worked on many spin-offs of the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee's “Vision for Greater Yellowstone” in my time with the Forest Service, both with today's Custer-Gallatin National Forest based in Bozeman and the Bridger-Teton based in Jackson, Wyoming. The first effort I became involved with was what became known as "the vision document" itself, based on an aggregation of differing national park and forest management plans done in 1987.

The point of creating a vision was to show that land managers were capable of working together in cohesive ways that considered the impacts of decisions across jurisdiction boundaries and did not result in outcomes that were at cross purposes. In other words, taking actions on one public land that harms another or spending money to address one problem that is caused by spending which created it.

The draft of that vision for Greater Yellowstone was vehemently resisted by members of the public who got their information about it from coffee shop talk—the equivalent of today's disinformation and hearsay proliferating on social media.

At one public meeting (or as the agencies called it, a “listening session”) in 1990, I was trying to understand why a ranching couple from southern Lincoln County (not part of Greater Yellowstone) was so set against anything in the document when it didn't directly impact them. They admitted to not having read it (and anyone who tries will find it uphill work, so their reticence was easy to understand).

Regardless of the document's content, they couldn‘t articulate what they objected to, except the fact that the vision document even existed. Others at the table expressed a belief that the vision was only the first step toward making the national forests more like the national parks with more restrictions on use and resource extraction. They saw a future in which their livelihoods allegedly could be eliminated.

The Bridger-Teton had just published its forest management plan, which didn’t emphasize traditional commodities as much as some wanted to see. Local mills were shutting down or moving elsewhere, and the merchantable timber around Union Pass which fed a mill in Dubois and old trees in the Wyoming Range were pretty much exhausted, at least what you could get to without building roads in steep places where they didn’t belong for both cost and environmental reasons.

So people had a chip on their shoulder from the get-go, blaming government for what had turned out to be unsustainable practices, and it seemed that in the listening session I was part of no one in the room liked anything about the vision, period—again, even though they didn't know what it was intended to do. Maybe part of that was owed to the fact a cohesive commonsense vision had never existed before.

Once the comments from the public at large came in, the agencies must have wondered what in the world to do with them. The majority of respondents felt the vision’s goals were unclear or inherently in conflict. Many citizens who weighed in wanted “naturalness” to be the overriding goal. Others felt strongly that there needed to be a clear statement that the Forest Service's multiple-use mission would remain unchanged.

They pointed out that in their minds the Forest Service is legally obliged to favor economics, i.e. providing resources, even finite ones, as commodities that could be cut down, removed from the ground or eaten (livestock grazing on grass) and then sold. Others felt the Forest Service need only consider economics and all factors, and what was needed was a comprehensive economic study.

Some felt that development in Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks already, in 1990, failed to meet the standard of protecting naturalness. Others reminded us that recreational development, when it grows in scale to become an industry, can be as, or more, detrimental to ecosystem values as grazing, timbering or mineral development.

Worth noting is that the actual vision document actually states that a consistent message from almost everyone was “an affirmation of the fundamental premise that the Greater Yellowstone is special to the American people, including local residents, and management should recognize its importance.”

Yes, it is special and deserving of safekeeping but how?

After an extensive public involvement effort and analysis of the comments, the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee concluded that people hoping for a so-called lock-up of the area’s resources would be disappointed, and those hoping for a business-as-usual approach would also be disappointed. This sounds a lot like the often-repeated adage among agency leaders, “Well, everybody’s mad at us so we must be doing something right.”

I often heard this, but, however accurate, is this the kind of rationalization we want when it comes down to doing the right thing—crafting a vision that will insure the special qualities of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem? Making sure it can persist into the future in the face of increasing pressure? We need to do better. The vision process of 30 years ago happened before climate change was recognized as an emerging threat and population growth was not a major issue in Bozeman and elsewhere in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. In fact, the assertion that those advocating for better protection were interested in "locking it up" was an inaccurate depiction.

This sounded a lot like the often-repeated adage among agency leaders, “Well, everybody’s mad at us so we must be doing something right.” I often heard this, but, however accurate, is this the kind of rationalization we want when it comes down to doing the right thing—crafting a vision that will insure the special qualities of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem? Making sure it can persist into the future in the face of increasing pressure? We need to do better.

The 80-page draft was finalized in the form of a much briefer and watered-down direction. Gone was the word vision; now it was called a “framework” for interagency coordination. You can find this and other documents by clicking here.

To assuage the fears of grazing permittees like the ranching couple at my table, the document included a statement about coordinating with state wildlife agencies and permittees to “define wildlife/livestock inter-relationships (whatever that means) and appropriate forage use levels” in the national forests.

Grazing has been managed for decades through annual operating plans that do basically the same thing, so this statement represented nothing new. Business as usual.

Moving on from attempts at interagency coordination, who today remembers the once-active Yellowstone Business Partnership, which involved the tri-state chambers of commerce, private businesses and national park concessioners? It seems, from my cursory internet search, to have died a quiet death around a decade ago.

I attended some of its meetings through the 1990s and found the topics inspiring, the people energized, and the prospects for coordination excellent. My take-away from those gatherings was hope and optimism. It wasn’t just the land management agencies that were trying to work together to protect a place which we all consider special—so was the private sector. Perhaps the effort still continues in a less conspicuous way?

While working for the Forest Service I also participated in various sub-committees assigned to work on grizzly bear conservation, outfitter-guide policy, winter visitor use and an assessment of the general recreation resource around the ecosystem. From these I learned not only about the effects of brief tenures among agency leaders, but their timidity in the face of public blowback.

While working for the Forest Service I also participated in various sub-committees assigned to work on grizzly bear conservation, outfitter-guide policy, winter visitor use and an assessment of the general recreation resource around the ecosystem. From these I learned not only about the effects of brief tenures among agency leaders, but their timidity in the face of public blowback.

One of these interagency teams was assigned the job of completing a winter visitor use assessment for the Greater Yellowstone region beginning in 1994. This followed a snowmobile trip involving Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee members into Old Faithful, during which eyes were opened about how much winter use had grown.

By 1992 Yellowstone had already exceeded its projected use level for the year 2000, and with visitation increasing every year the park experienced fuel shortages and full sewage tanks. On most weekends, air quality standards were exceeded at the West Entrance as people queued up to pay their fees. The winter use group was convened as a result of heavy snowmobile use in Yellowstone, but it also addressed all kinds of motorized and non-motorized recreation.

In the middle of our work, the Forest Service got to experience what happens when the national parks close their gates—a federal budget impasse resulted in a three-week government shutdown at the end of 1994, just as Christmas visitors were about to descend on Yellowstone.

The Bridger-Teton and its winter resorts helped take up the slack. People were disappointed in not being able to see Old Faithful erupt on Christmas morning but they found some great trails and scenic places instead.

One rustic resort halfway up the Greys River served lunches to snowmobilers. It was used to handling around twenty people in its small dining room, but found itself serving 200. So the conversation continued—how and where was the land going to accommodate everyone?

We sent newsletters and a draft of the assessment to the public, and the blowback began.

An effort to classify areas according to appropriate levels and kinds of use was seen as a way to place more restrictions on snowmobiles than those already in place. Coffee shop talk was replaced by more incendiary rumors circulating in bars and taverns, and a few snowmobile advocates would spend a bit of time over beers before showing up at the public meetings.

I watched a handful of them shout down anyone from the national parks or national forests before we could even explain the work that had been done. Reasonable people who came to the meetings to learn and give input left early, muttering about how they couldn’t waste time listening to a bunch of drunks yelling.

As one meeting deteriorated into chaos, I looked around. There I stood at the podium in my Forest Service uniform while two of our district rangers sat in the audience not wearing theirs. The forest supervisor did not attend at all, and I felt pretty much hung out to dry. It wasn’t until the park superintendent at Grand Teton stood up and gave the audience That Look that things settled down.

Fast-forward to take a current look today at the response coming from certain backcountry skiers in regard to an interagency effort to preserve a small and unique population of Rocky Mountain bighorns in the Tetons. After skipping the informational meetings about the ecology of this sheep population, a few skiers showed up when the maps were brought out and made their self-interest clear, not only in the way they wished to not have their fun interfered with by wildlife.

This is not to blame any particular interest or user group. It’s not only snowmobilers who are worried about access: fast-forward to take a current look today at the response coming from certain backcountry skiers in regard to an interagency effort to preserve a small and unique population of Rocky Mountain bighorns in the Tetons.

After skipping the informational meetings about the ecology of this sheep population, a few skiers showed up when the maps were brought out and made their self-interest clear, not only in the way they wished to not have their fun interfered with by wildlife, but by standing in the back next to the food table until no one else was able to even grab a cookie during the break—the food was gone.

How does one say this politely? We are selfish.

In my work, I have tried to recognize people’s legitimate concerns in spite of how the message is delivered. I liked that couple from Kemmerer at the listening session and I’m sorry they didn’t like me very much, or we could have had a better talk.

I liked most of the people who came to give their views on national forest management in any context, a few belligerent drunks excepted. But what do you say to someone who believes the national forests are being managed as if they were all wilderness, or to the person who thinks cutting one stick of timber is going to ruin the place forever? How do you deal with false impressions based on misinformation? How does the truth get out there if the media shows up and merely quotes people with opposing views without sifting out what the facts actually are?

What do you say to someone who believes the national forests are being managed as if they were all wilderness, or to the person who thinks cutting one stick of timber is going to ruin the place forever? How do you deal with false impressions based on misinformation? How does the truth get out there if the media shows up and merely quotes people with opposing views without sifting out what the facts actually are?

I learned that, as a civil servant, you don’t say anything because there is no interest in hearing it from you. You listen, you write down the concern and pass it up the line, where even after sanitizing it to remove expletives and flagrant untruths, it is likely to be dismissed for lack of anything meaningful within, further pissing off the one who said it.

After the winter use project was completed I was part of a group of agency staff chartered to provide a similar assessment of summer and fall recreation in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Our team thought it was important to recognize the region’s value as a reservoir of wildness, not only for recreation but for wildlife, water quality, and the gamut of other basic resources.

The project was meant to describe and map the existing wild land spectrum during the snow-free season, identify regional trends in recreation use and demand for particular wild land settings, and give some recommendations. The key ingredients to our project were the maps we envisioned, one showing the range of settings for recreation from the most-pristine to the magnet places in or near developments that could allow the most people to experience and connect with nature.

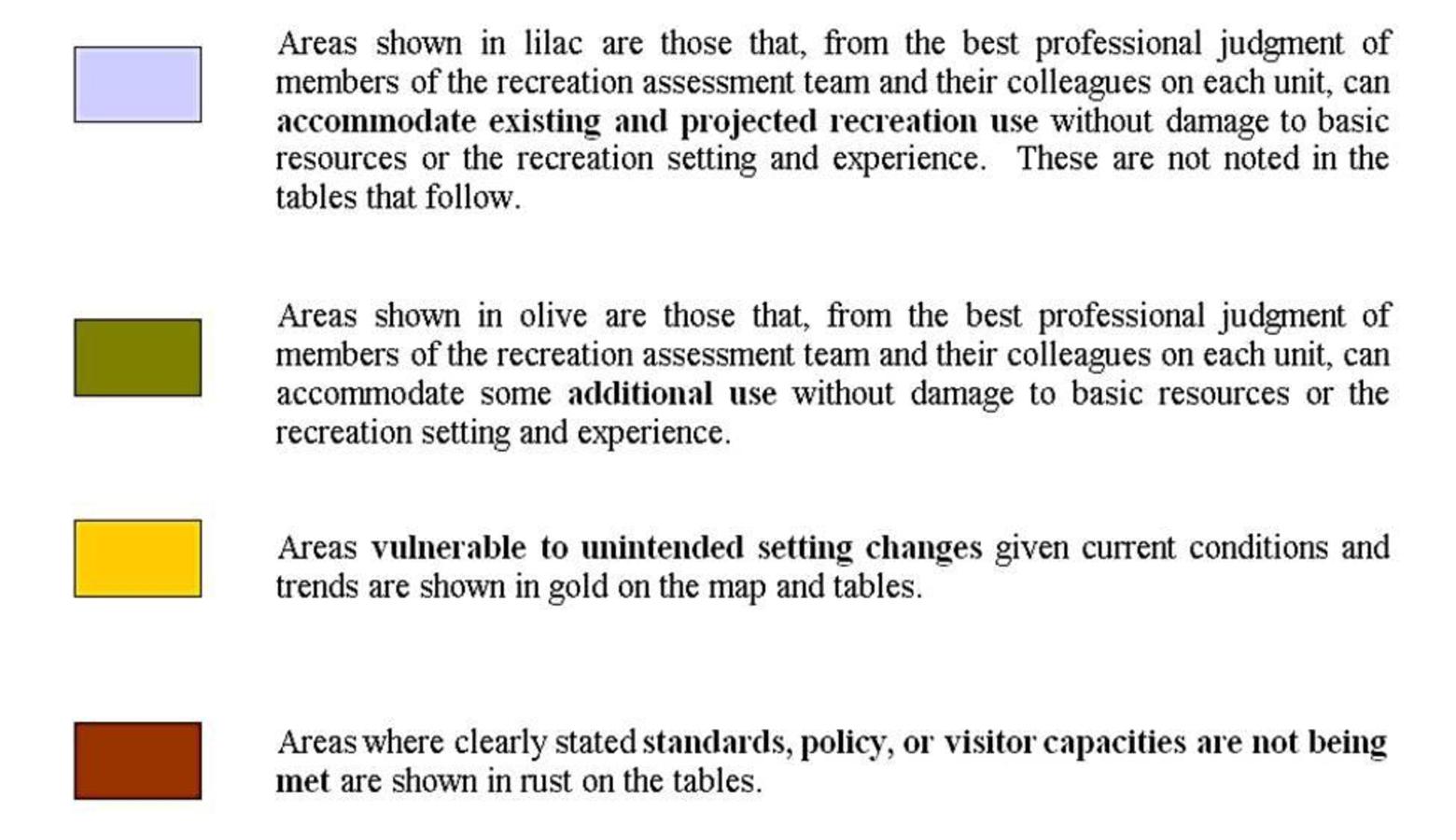

The other map was meant to identify site-specific details that could guide future management. Each mapped unit would have a description showing what it uniquely offered and whether it could sustain additional use without being damaged. We came up with four categories for this exercise and they are highlighted in the actual document.

Long before today, there was concern about overuse or growing human uses overwhelming natural settings. Even in 2001, some two decades ago when the recreation assessment began, there was a sense of urgency about whether our work was going to matter by the time we were done.

An early reality check on the project revealed some startling statistics similar to what was found about winter: The population of the region had increased 55 percent between 1970 and 1997 and the five fastest-growing counties increased by 107 percent. Recreation use of the Snake River Canyon in Wyoming rose by a 500 percent increase in the 26 years we’d been recording it.

On the Gallatin River commercial floating in the mid-1980s accounted for about 500 days; in 2001 it exceeded 17,000. And so on. Who knows where it is now.

During the four years the team spent on this project, agency personnel changes had their effect. Newly appointed members of the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee weren’t sure they bought into the original charter and others started to worry about what we might present, especially after the fiasco with the GYE vision document and smaller blow-ups with the winter use assessment.

Ultimately the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee decided they didn’t want analysis, potential management actions or recommendations after all. They didn’t want a desired condition defined or a monitoring protocol. They didn’t need us to remind them of how crucial the wildlands were to the ecosystem; they wanted to know what to do about the crowds at Old Faithful.

In the end, we delivered what was called a "technical report," where the maps we thought so important are buried. A 35-page condensed report was made public (also found on the GYCC web site), lacking the map, which was deemed too sensitive to share.

If someone’s favorite fishing hole was in a map unit colored brown (not meeting standards for resource protection), that might mean some kind of restriction was coming. I probably find it easier than some people to see why agency managers retreated from worthy efforts in managing recreation, trying to get ahead of the curve instead of waiting until a crisis developed.

After using best available science and developing rationale for any conclusions, they faced opposition not only from many members of the public, but also from their bosses, elected officials, and economic interests that saw the peerless wild country of the Greater Yellowstone region as little more than a cash cow. That is still the case.

The concerns that started the vision exercise and the recreation assessments over 20 years ago remain the same: recreational demand in the Greater Yellowstone region is growing rapidly while the land base is constant and filling up.

Technological improvements and increasing desire for extreme sports mean recreationists are penetrating farther from roads, and in some instances altering the land. Growing recreation brings resource and social impacts, such as the dispersal of noxious weeds, habituation or displacement of wildlife, and crowding.

The Forest Service has been trying since recreation management was first thought about to keep the forests from becoming a free-for-all in which no one gets the experience wanted and basic resources are damaged. But for some, care for the land only goes as far as the front tire of our bike or the scene in front of our camera lens.

We’ve spawned such a me-first society that maybe only a plague brought down upon us will make us rethink that. What we need is a return to me-as-part of a greater whole, instead of me-as-center.

We’ve spawned such a me-first society that maybe only a plague brought down upon us will make us rethink that. What we need is a return to me-as-part of a greater whole, instead of me-as-center.

Managing recreation in a national forest or park can only work if people are willing to practice some self-discipline based on understanding and caring about the health of the whole. The most basic ideas of public land recreation management come from research done by the agencies and universities, and that research, completed by experts, is often ignored by those making the decisions.

Decision-makers mostly want to do the right thing, but often their careers are at stake if they push too hard. This has to change, and in the current political climate it isn’t likely to very soon.

Increasing recreation use brings more conflict. People complain to the agencies. Can’t there be a trail without bikes on it? Can’t those horses go somewhere else? Can’t we have more and more trails so we can go farther and not see the same thing every day? The pressure is on, and budgets are down.

Most of us try to do the right thing, but it only takes one ignorant person to spoil an outing for many. It only takes one clueless but successful elk hunter to leave the waste from home butchering at a popular trailhead to have others in danger from bears. Or one wood hog with a winch and a horse trailer to take more than his share of firewood so no one else can get any. It’s the same impulse that makes people hoard toilet paper—me first. Me only.

This will not end well for us if we don’t change. We humans are a diverse lot, with many conflicting opinions. But some people have had a vision for Greater Yellowstone for a long time—the agencies, business groups, and local governments among them. It’s not that a vision doesn’t exist, but in order to be as inclusive as possible, to fit the needs of the wide-thinking visionary and the guy with the Wyoming Native bumper sticker, it is going to be fairly broad and abstract.

What can we all agree on—that we love and value this place? For each of us it means something different. Plus, regardless of how useful a vision might seem, regulations differ by county, state, and agency. Laws favor private rights above the public interest.

There is, at Mountain Journal pointed out in the first installment of this series, no overarching safeguard in our system of government that will keep us from overwhelming this last great place. Except: what if we had a check on population, profligate prosperity, and waste?

This can come in the form of enlightened self-control, or in the form of a catastrophe. Some of it is not up to us—the coronavirus, the meteor, the climate. But some is. The self-quaratine we face might give us enough pause to consider how lucky we are to have clean, cold air to breathe on a walk in the woods with no danger of coming closer than six feet from another.

There is no overarching safeguard in our system of government that will keep us from overwhelming this last great place. Except: what if we had a check on population, profligate prosperity, and waste? This can come in the form of enlightened self-control, or in the form of a catastrophe. Some of it is not up to us—the coronavirus, the meteor, the climate. But some is.

It might help us appreciate the color variations of the common juncos in the front yard. Or the beauty of spring clouds, the rising light, the return of migrating cranes and geese. There is much to appreciate, even when we are sequestered at home. Let’s put aside for this moment our arguments over whether a mountain slope should be shared with wildlife or a trail shared with others who prefer a different form of recreation than we do. In the face of a global pandemic none of that really matters.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Also read these related stories in Mountain Journal (click on them)