Back to StoriesWhy A Group In Jackson Hole, Devoted To Unbridled Adventure, Conservation And Diversity, Is Under Fire

July 23, 2019

Why A Group In Jackson Hole, Devoted To Unbridled Adventure, Conservation And Diversity, Is Under FireSHIFT can still have real impact but only if it is willing to shift itself

What is environmental advocacy? As we make a clear-headed assessment of current social, demographic and environmental trends, where will the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem be in 30 years? Where will public support for conservation in America be?

This summer I’ve been having lively discussions about the meaning of advocacy with Mountain Journal’s intern who is here in Bozeman with us from Whitman College for a few months. I’ve asked him to reflect upon, and explore, this question that MoJo keeps revisiting: Is simply partaking in any outdoor activity an act of conservation?

Can a person who hikes into the Greater Yellowstone backcountry, for instance, claim that, simply by moving one’s legs, they are doing something positive and meaningful for the places we are exploring?

Think about this proposition because it’s a belief some people have.

Can trail building be counted as an act of conservation? Are we being conservationists and promoters of water quality when we wet a dry fly on the river or raft it? Are we confronting and registering our concern about climate change when we downhill ski?

Are we promoting less resource consumption when we sort materials for the recycling bin yet have no idea where the paper, glass and plastic are ending up?

Are we doing something bold and brave for the environment by “liking” a story about environmental threats on Facebook or posting another pretty picture on Instagram?

Such inquiries can be extended to any outdoor activity. It all comes down, of course, to identifying what exactly are we trying to conserve—and for what? No one wants to discuss these things because they make us squirm and force us to think beyond our own protective comfort zones and singular self-interest.

The late Jackson Hole conservationist Mardy Murie, in the very first discussion I ever had with her as a 24-year-old journalist in 1986, told me this on her cabin’s front porch in Moose, Wyoming. She said conservation is about protecting rare priceless things from being overrun by common thoughtless things; it’s not about focusing purely on what benefits us but what perpetuates the things in nature that give us inspiration and which cannot advocate for themselves, such as animals, rivers and old-growth forests.

Conservation, Mardy Murie once told me, is about being able to self-reflect on what society is willing to give up—i.e. exploit less of—in order to achieve more for the larger public good—in this case, advancing the sustainability of ecological health that benefits people and allows wildlife to persist.

Conservation, she noted, is about being willing to take a risk, to advance a right cause that might be unpopular. On the same porch stoop where Murie and I sat, Aldo Leopold had been there four decades earlier. Among the many observations Leopold, as a forerunner of ecology made, two are poignant here:

"We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we begin to use it with love and respect."

and

"Ethical behavior is doing the right thing when no one else is watching—even when doing the wrong thing is legal."

° ° ° °

Amid these three years of the Trump Administration, public-land-adoring Americans and those who cherish public wildlife and support having tough environmental protection laws on the books have been left reeling by actions taken by the President, his advisors and their friends in natural resource extraction industries.

Citizens want to “do something” in response, but what? At the same time, the outdoor recreation industry—of which all of us are connected through our role as consumers of stuff—has claimed that getting more people venturing into wild places will result in better landscape protection and help repel destructive policies. But how does that work?

Outdoor recreation is big business. It creates jobs, just as the mining, timber and energy industries do. It annually generates $887 billion in economic activity in the US and its growth model depends on selling more products to more people and getting more people into environs where they recreate so they will buy more products. This is the feedback loop. But how are the uses this industry as a whole promotes directly benefitting, say, survival prospects for a rare grizzly bear population in Greater Yellowstone inhabiting a fine amount of space?

Conservationists are born through their bond with nature. But how does building more mountain biking and e-bike trails and claiming, falsely, that access to public lands is a serious problem—result in better protection of, say, Greater Yellowstone's unrivaled wildlife migration corridors? How would the pushes made by Jackson Hole packrafters to overturn a historic river boating ban in Yellowstone have contributed to better conservation of America’s oldest national park?

What most of us fail to realize is that all of these things contribute to the consumption of a finite and wild nature. How do we know this? Because wildlife, as is found in Greater Yellowstone, still only persists where large numbers of people and human activity are absent.

Like everyone living in Greater Yellowstone, including those affiliated with Mountain Journal, and those of you who read us, we love recreating in the outdoors and we are dedicated to the ideal of sustainability—but sustainability of what? The argument that consuming more of nature for our own needs leads to better conservation outcomes is directly parallel to the Gordian knot premise, promoted by some, that Jackson Hole and Bozeman can develop their way out of serious growth-related problems.

° ° ° °

Consider now the annual Jackson Hole SHIFT Festival, whose mantra is "where conservation meets adventure." Held in October it was originally established with seed money from the local Jackson Hole Tourism and Travel Board, with the stated hope the conference would generate more commerce for the economy during the autumn shoulder season by having attendees stay in local hotels and spend money with merchants.

SHIFT wouldn't matter except that it caters to young people and its organizers claim they want to promote a radical shift in how people relate to the environment. They want to be a national voice. They claim that promoting rapidly-expanding outdoor recreation, and recruiting non-white people to partake in their facilitated discussions, will yield huge conservation dividends. But how deep, really, is SHIFT's thinking?

These days, by its own doing, SHIFT is under a cloud of intense national negative scrutiny by members of the diversity movement and wildlife conservationists.

Critics say the festival has only really been about white recreationists pushing to open more parts of the still-wild backcountry to their own activities and asking the ethnic and gender diversity movement, which feels tokenized, used and abused, to give them cover. At least, that is one assertion, as has been articulated by recent participants, who even asked the founder of SHIFT to resign.

Read more about that here (the allegations), here (a local news story in Jackson Hole about the allegations), here (response from SHIFT board of directors), and here (an apology letter from SHIFT Executive Director Christian Beckwith), then judge for yourself.

In the wake of those criticisms, Teton Science Schools distanced itself from SHIFT and its Emerging Leaders Program. Outside Magazine this summer featured a story titled "What Happened At The Shift Festival? A public condemnation of the SHIFT Festival's attempts to promote diversity, equity and inclusion is indicative of broader issues in the outdoor industry."

° ° ° °

Diversity. Equity. Inclusion. They converge in the acronym DEI. Familiarize yourself with it, for if you care about public lands, it is as important as knowing what the letters NPS, USFS, USFWS, BLM, ESA, EIS, EPA, USGS and NEPA mean for Greater Yellowstone and public involvement; indeed, the future of environmentalism in a changing America hinges on all of us becoming conversant with what DEI represents.

A recent report from the Brookings Institution came with this headline "The US will become 'minority white' in 2045, Census projects: Youthful minorities are the engine of future growth."

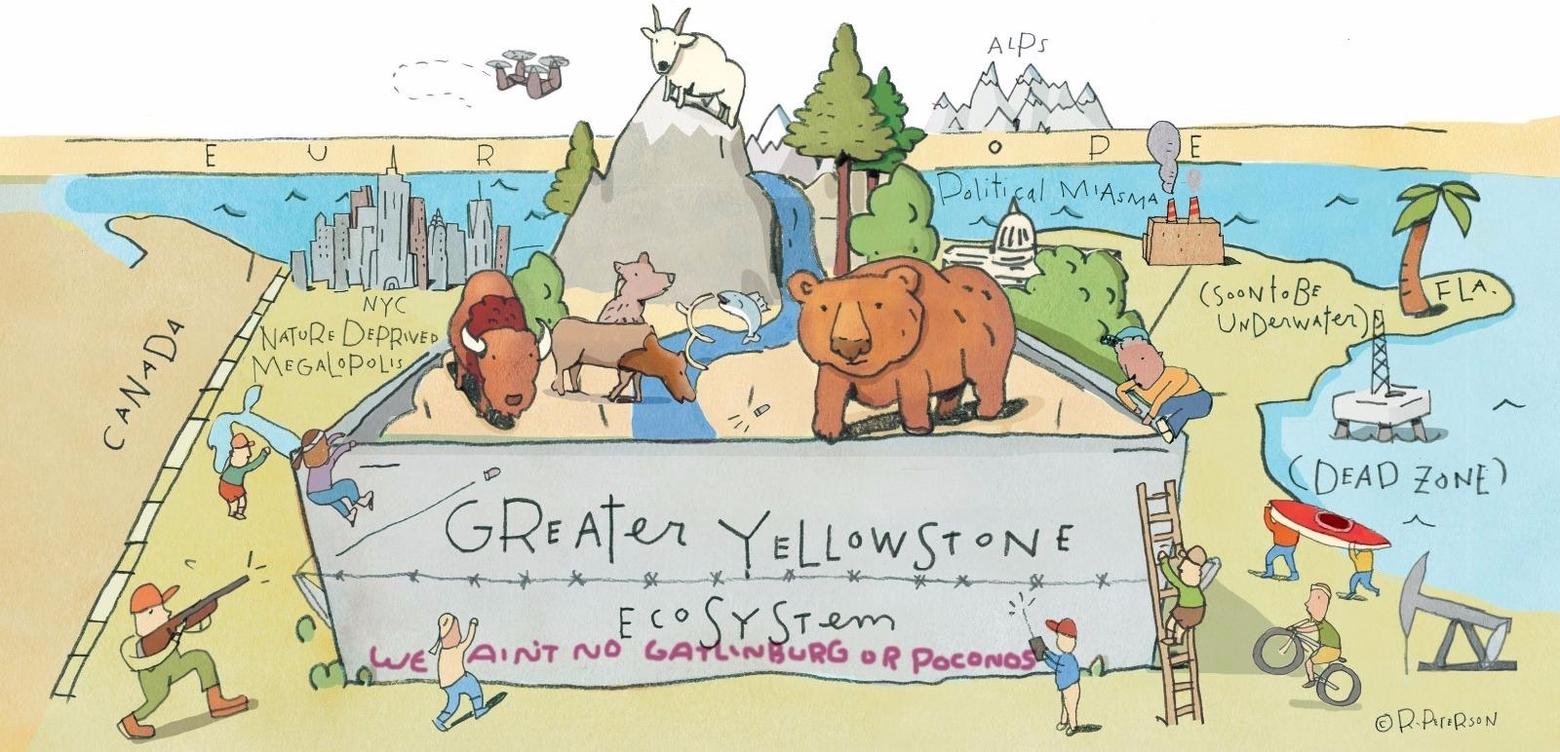

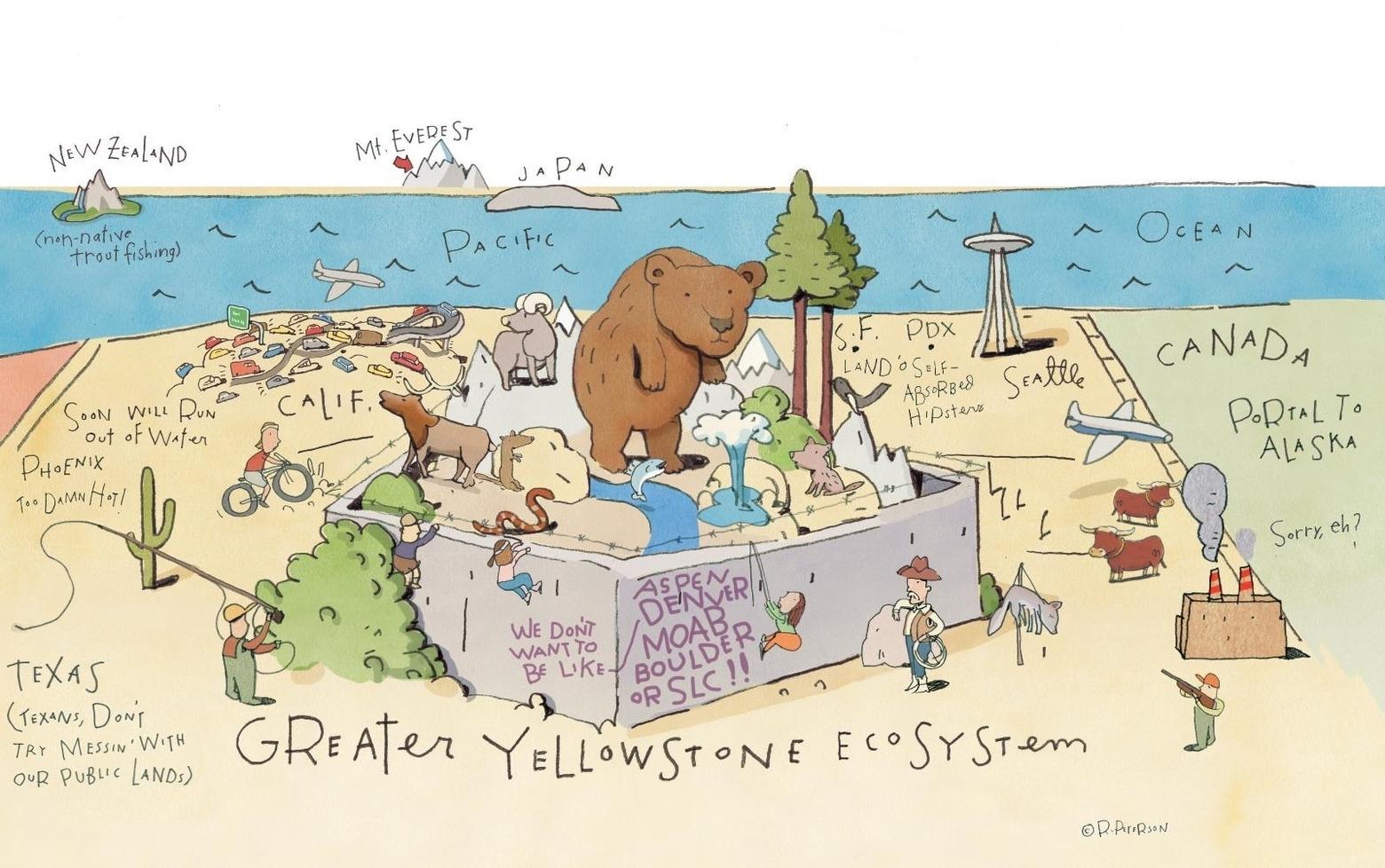

Greater Yellowstone exists in a bubble—of still-healthy public lands as evidenced by the unparalleled assemblage of wildlife they support, of robust interest in hunting and angling despite significant declines in hunting and fishing participants elsewhere, in booming growth driven by environmental quality which creates a paradox, and in a region that is overwhelmingly white, save for a rich, largely-ignored diversity of indigenous nations, languages and cultures plus a Latino community often treated as invisible.

Inherent to SHIFT's agenda is that if only more minorities took up climbing, mountain biking, downhill skiing, kayaking, hunting and fishing—recreational pursuits currently favored by upward-mobile white people—then protection of the natural world will be secured. The problems with that line of thinking are many, for it condescendingly presumes that if white recreationists convince non-whites to behave more like them, then the status quo will be maintained. Yet it's precisely the unsustainable status quo that is the problem.

Further, major rollbacks of environmental protection are now happening during the Trump Administration in spite of the outdoor recreation industry's economic statistics. And, don't forget, some of the proposed rollbacks are happening with complicit support from certain recreation groups, like factions within the mountain biking industry, backing legislation to weaken Wilderness Act protections.

° ° ° °

What’s missing from SHIFT? Plenty, actually. One could also strongly argue that SHIFT does not understand or appreciate DEI—notions of diversity, equity, and inclusion—as it relates to the broader values of nature. It is in these values—a healthy environment for all inhabitants—where the essence of conservation resides.

In 2019, SHIFT is trumpeting the already-abundantly-obvious facts that spending more time in nature is good for our health and that monetizing outdoor experiences and selling more outdoor gear are good for the economy. This is hardly a new revelation.

Not long ago, I reached out to SHIFT and suggested they might also consider featuring regular sessions helping attendees understand what they might do to protect the ecological health of wild places that are finite and exhaustible. After all, the conference is held in Jackson Hole, located in the center of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Why here? If Greater Yellowstone is treated as merely a generic backdrop, why not hold the conference in Denver, where Outdoor Retailer is held, or Washington, DC, or Las Vegas or Disneyland?

Others have made similar recommendations to SHIFT, about emphasizing what it takes to maintain ecological health, because doing so would represent a real shift in thinking about conservation that lasts—and it could help drive how elected officials approach policy. But SHIFT wants little to do with telling the recreation industry that people seeking adventure in Greater Yellowstone might need to be limited in their numbers or more carefully managed in order to protect wildlife and the character of lands not yet over-trammeled.

We as a society are very good at responding to conflicts rather than preventing them. As several people have noted, it is difficult to get people to understand something when their salaries depend upon their not understanding it.

This is part of the response I received from SHIFT: "The impact we have recreating or sightseeing in wild spaces, particularly ones such as the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem that receive millions of visitors each year, can be such a degree we negatively impact the places we love. The environment is not just a resource to be exploited, either for oil or experience. It's a tough balance to strike; minimizing impact while maximizing the interactions that keep us connected and invested in the places around us. Climate change, as you note, will certainly render this debate obsolete if we don't change our path."

Ah yes, balance.

"Balance," like "sustainability," is one of those anodyne words that sounds good but means practically nothing if not subjected to closer examination of what the end-goal is. Balance is also the word that gets invoked when one is unwilling to make hard choices based on self-reflection.

The much-touted "balance" achieved with intensive natural gas drilling in the Jonah Field and Pinedale Anticline of Wyoming's Upper Green River Valley has resulted in huge negative impacts on mule deer, pronghorn and imperiled Greater sage-grouse.

The "balance" being promoted by some factions of the mountain biking community would bring a radical alteration of The Wilderness Act, resulting in mountain bikers being able to inundate Wilderness lands where they are now prohibited. In Greater Yellowstone, scientists say allowing mountain bikers to ride in Wilderness would displace grizzly bears from desired habitat and create safety issues for both people and bruins.

"Balance" is the word the Trump Administration used to justify the radical shrinkage in size of national monuments in southern Utah in order to appease interests that want to extract things from within the original protected areas.

"Balance" oftentimes serves as a rationalization for steadily whittling away at things that should be inviolate. Ask a trout to tell you what it thinks about "balance" when it comes to the importance of reliable, unpolluted water in a stream or elk about the necessity of having enough secure winter range to sustain it in the middle of January.

"Balance" oftentimes serves as a rationalization for steadily whittling away at things that should be inviolate. Ask a trout to tell you what it thinks about "balance" when it comes to the importance of reliable unpolluted flows in a stream or elk about the necessity of having enough secure winter range to sustain it in the middle of January.

"Balance" in most of American history has meant some groups of humans taking what they want from nature and forcing others—less influential people and wildlife— to adapt.

"Balance" to many in the human diversity movement is doublespeak for exploitation. Ask a Native American to explain how well "balance" has worked out for them.

Never has SHIFT vigorously asked its attendees to consider what wildlife in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem needs in order to persist, despite wildlife abundance—which exists ironically because of conservation— being a major driver of Greater Yellowstone's economy. In fact, SHIFT in the past has smugly dismissed the cautions of those—scientists and others— concerned about rising recreation pressure.

Below, verbatim, is what the internationally-respected science journal Nature says about the importance of biological diversity and its connection to the health of people:

"Biodiversity is the diversity of life on Earth. This includes the richness (number), evenness (equity of relative abundance), and composition (types) of species, alleles, functional groups, or ecosystems. Biodiversity is rapidly declining worldwide, and there is considerable evidence that ecosystem functioning (e.g., productivity, nutrient cycling) and ecosystem stability (i.e., temporal invariability of productivity) depend on biodiversity. Thus, biodiversity declines may diminish human wellbeing by decreasing the services that ecosystems can provide for people."

What does SHIFT think is causing biodiversity declines and what is it doing to prevent them from continuing?

I remember having a chat with SHIFT organizers a few years ago and they were utterly unaware of the history of public lands in our region and why specific environmental laws were enacted to prevent over-exploitation. They had little interest in knowing of previous conservation battles that had been waged and how advocates set aside their own self-interest to instead safeguard lands and wildlife diversity they might never see or be able to "use."

Obviously well-intentioned, SHIFT has the potential—still unrealized— to move the public conversation about conservation in Greater Yellowstone forward. Yet so far its focus has been on promoting a boundless recreational use of nature, not conserving it for anything other than human self-interest. The magic of Greater Yellowstone, however, emanates from a multitude of intrinsic things that have disappeared elsewhere.

What does "where conservation meets adventure" mean and when has pushing greater volumes of people and users into sensitive environments ever resulted in them remaining wild? Ponder this: what if Jackson Hole and Bozeman became meccas for the most physically fit outdoor athletes in the world yet wildlife vanished? What would be lost?

Festival organizers have balked at addressing the most difficult issue of all, which is asking us to contemplate how much we're willing to alter our own consumptive behavior in order to secure ecosystem health. And, from a conservation perspective, they have failed to promote higher levels of ecological awareness, the uniqueness of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and, as indigenous people say, respect for diversity of all life forms, whether they can be monetized, served on the dinner table or not.

Caring for nature is not an elitist fetish of white conservationists though, no question, the benefits of conservation, when justified for economic reasons, have accrued more to wealthier white people than anyone else. Witness the crisis of affordable housing in any attractive mountain community.

Indigenous peoples have the most sophisticated understanding of biodiversity among all humans on earth. They regard the web of life as sacred. They understand we are not separate from other living things; our survivals are intertwined in the mutual life-support systems we depend upon.

Some claim that Yellowstone is a racist, elitist construct because its creation resulted in the extirpation of native people. That's painfully and irrefutably true, and it's also true that the same claim applies to the entire North American continent. It's also true that today Yellowstone and the public lands around it represent many of the last refuges for rare species of public wildlife and everyone, yes, everyone, has an opportunity to be stakeholders in their survival.

You can simultaneously be a fierce proponent of championing human rights, diversity, equity and inclusion, and be devoted to protecting habitat for wildlife; the two are not mutually exclusive.

Fortunately, as the Reverend and Dr. Gerald L. Durley in Atlanta, has reminded me: no one needs permission from someone else to care about the natural world. No one needs approval from the patriarchy to become an advocate for nature’s protection. No one needs to be anointed a leader by someone else in order to be one. That power resides in each of us—and not because of our racial or gender identity, or political party affiliation, or because we’re a dues-paying member of an environmental organization or hunting, fishing and recreation group, or because a person is invited to fly across the country to attend the SHIFT conference in privileged Jackson Hole.

Durley is a leading figure in discussions about faith-based conservation, environmental justice, climate change, science-based arguments for protecting biodiversity, and bringing the awe of nature into the lives of people who do not experience it everyday.

Fortunately, as the Rev. Gerald Durley in Atlanta has reminded, no one needs permission from someone else to care about the natural world. No one needs approval from the patriarchy to become an advocate for nature’s protection. No one needs to be anointed a leader by someone else in order to be one. That power resides in each of us—and not because of our racial or gender identity, or political party affiliation, or because we’re a dues-paying member of an environmental organization or hunting, fishing and recreation group, or because a person is invited to fly across the country to attend the SHIFT conference in privileged Jackson Hole.

We know this much: there is not a singular right pathway a person must take to become an advocate for nature but most people recognize the wrong course is one that leads to ecological destruction, environmental injustice, impoverishment of people and loss of species—all of which are linked to the colonial mindset that the diversity movement is challenging. Today, one doesn't have to go far to encounter anger from those who say the conservation movement is guilty of tokenization when confronting its lack of diversity, equity and inclusion.

The only way to construct a better conservation movement, where everyone feels a sense of belonging and listened to, is by having a more diverse one that includes respect for all people and recognizes the rights of all creatures to exist.

One new notable group in Greater Yellowstone is Bozeman-based Earthtone Outside, whose mantra is "an outdoor community for people of color." I enjoyed having a recent chat—and listening—to a few of Earthtone Outside's courageous thought leaders. They didn't emerge because SHIFT anointed them; they've risen organically, feeling their own innate sense of awe.

It isn't how to capitalize on "outdoor recreation" and adventure they are promoting; Earthtone Outside functions as a safe gathering place for like-minded people, drawn to having a deeper, more contemplative connection with nature that rings true to them. Are they interested in wildlife conservation and do they appreciate and understand the specialness of Greater Yellowstone? Yes, absolutely. You'll be hearing more about this organization, and its member perspectives, in the future at MoJo.

Conservation, Mardy Murie once told me, is about being able to self-reflect on what society is willing to give up—i.e. exploit less of—in order to achieve more for the larger public good—in this case, advancing the sustainability of ecological health that benefits people and allows wildlife to persist.

Let us consider a stark and perhaps inevitable possibility: maybe protecting wildlife in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem doesn't matter. Maybe Americans don't care if this national treasure of large mammal biodiversity persists. Maybe, compared to other challenges facing humanity in coming decades, the natural wonders still preserved here will be looked back upon as a squanderable luxury. Maybe Greater Yellowstone is destined to follow the same destructive path as the Florida Everglades and the salmon and old growth ecosystems of the Pacific Northwest, where humanity has so fractured their function, it becomes irretrievably compromised and broken.

Without bold acts of conservation taken by previous generations, as flawed as some might have been, we wouldn’t be referencing the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem's significance today as a globally-extraordinary region that belongs to all of us. Without new bold, broader-minded acts of conservation being adopted now, in the face of growing human pressures and climate change, we may lose the natural qualities that still make Greater Yellowstone uncommon.

SHIFT, other than adopting token slogans, has done little to take the ethical introspections of Murie, Leopold and others to heart. "We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us," Leopold wrote. "When we see land as a community to which we belong, we begin to use it with love and respect."

Without really confronting these tough questions with a big-tent, multi-perspective mindset, without espousing humility and respect for the fragility of nature, without seeming to appreciate why Greater Yellowstone's biodiversity persists, and without answering the question, What is environmental advocacy—and for what interest does it serve? why does the conference exist at all?