Back to Stories

September 30, 2021

Yellowstone Wolf 302 Latest Star In Rick McIntyre's Lobo Trifecta

It's not easy surviving as a wolf in America's oldest national park—and this doesn't even include the perils that loom for wolves from humans once they cross the northern border into Montana

by Norm Bishop

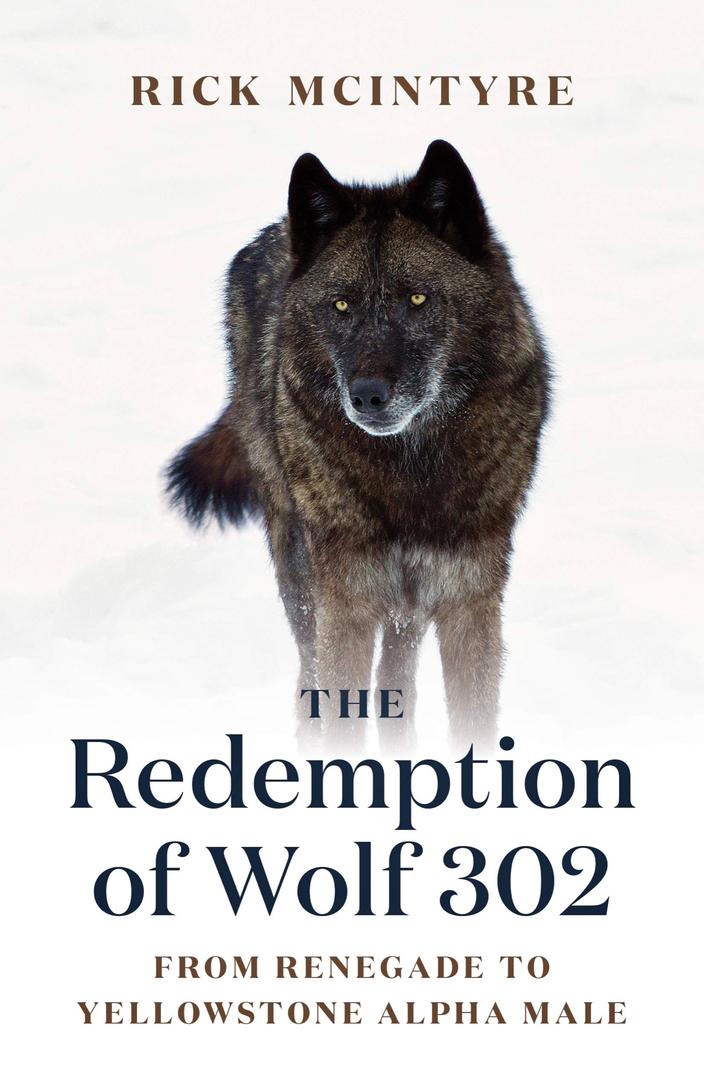

When a hockey player scores three goals in a single game, the player may win a hat—or a cascade of hats. In my view, Rick McIntyre has scored a hat trick with his three books on Yellowstone wolves: The Rise of Wolf 8, The Reign of Wolf 21, and now The Redemption of Wolf 302.

Each wolf’s story, the first from 1995 and the last from 2009, adds breadth and depth to our understanding of wolves—a species that can well afford more human appreciation of its kind. And happily, there are more books to come.

The hero of The Redemption of Wolf 302 demonstrates one of the most predictable traits of wolves: unpredictability. He first comes to our attention as a rake and a renegade a bit beyond 2 ½ years of age, flitting from pack to pack, breeding with multiple willing females and then retreating to his home pack. Later, he joins packs—always as a subordinate, but managing frequently to break the “rule” that the dominant pair are the only wolves in a pack that breed.

Finally, having survived to an age well beyond that of the average wolf, he shows the world that he is a respon-sible, caring, self-sacrificing adult who hung back to protect his pack when they were under attack—and lost his life to their pursuers. In so doing, he fulfilled his legacy in the manner and spirit of his predecessors, Wolf 8, Wolf 21 and others.

Do you think that, among wolves, you will find relentless killers? Or that wolves can be caring, selfless parents? Right both times.

In The Redemption of Wolf 302, we witness an invading pack besieging the dens of a resident pack, keeping the new mothers from reaching food or water until all their pups die. The invaders follow up by killing the resident pack’s adult males.

In a nearby valley, we track the lives of warrior wolves that pin their enemies and then let them live. Those same warriors allow their pups to defeat them

in wrestling matches and exhaust themselves carrying meat to pups from carcasses that may be ten miles from the pups’ den.

If you think a wolf blunders around, blindly guided by instinct, think again.

In The Redemption of Wolf 302, it becomes obvious that a wolf learns from birth to death. She relies on experience to avoid a second kick by a vigorous bison that flipped her 15 feet through the air, turning her 360 degrees before she landed.

Wolf 480, nephew to Wolf 302 who eventually became the Druid breeding male, uses an ancient Chinese battle tactic to win over an opposing group that outnumbers his: Charge as though you are the stronger unit, and win by spreading fear among your adversaries.

If you believe that elk are easy for wolves to kill, read McIntyre’s account in The Redemption of Wolf 302 of the Slough dominant pair both getting stomped, the male twice, by an elk cow they’d chased into a creek. After one wolf was able to grab a hind leg, other wolves rushed in as the elk got into water so deep they had to swim.

Finally, the dominant female swam up and got a good bite on the elk’s throat. As six wolves surrounded her, the elk died and drifted to a sandbar, where 20 wolves fed on her. Rick observes that about 1 percent to 5 percent of hunts are successful.

In The Redemption of Wolf 302, we learn about the hazards wolves face as they hunt to feed their families. McIntyre needs 7 1/2 pages to describe the “occupational injuries” 302 and others have.

Eight Druid pack wolves tried to kill a bull elk that took a stand in the river and shook them off. The wolves gave up and paddled to shore. It is dangerous for 100-pound wolves to take on prey up to ten times their weight. Wolves get gored by antlers or horns. They get kicked in the head and lose teeth. Or, like Wolf 302, get kicked so hard they spin through the air before crashing to the ground. One wolf got butted over a cliff and died. Others were stomped or knocked down; one was kicked down a riverbank and took six hours to recover.

It is dangerous for 100-pound wolves to take on prey up to ten times their weight. Wolves get gored by antlers or horns. They get kicked in the head and lose teeth. Or, like Wolf 302, get kicked so hard they spin through the air before crashing to the ground. One wolf got butted over a cliff and died.

Former Yellowstone Wolf Project leader Mike Phillips examined 225 wolf skulls in Alaska; 25 per-cent had suffered blunt-force trauma. A paleopathologist who examined Wolf 8’s skeleton said, “I do not understand how an animal could live through this.”

In his 1978 classic, Of Wolves and Men, Barry Lopez observes that we all make our own wolves, mostly by our imaginations. We recall the story of the five blind men and the elephant. To one, bumping into the beast’s side, it resembles a wall. To another, touch-ing the tusk, it is like a spear. A third, feeling the tail, says it’s like a rope. The fourth feels the leg and thinks it’s like a tree. To the fifth, feeling the ear, the elephant is like a fan.

Fortunately for the readers of The Redemption of Wolf 302, author Rick McIntyre is in com-mand of all his senses, aided by hun-dreds of other observers, equipped with a 60-power field scope, and has recorded every detail of what he has seen wolves do for more than 20 years; in one period, Rick observed wolves every day for 892 days. Now, we have a complete picture of the wolf.

Two decades in Yellowstone, observing and recording wolf behavior daily—and great skill in telling their story—have enabled Rick McIntyre to reveal to armchair wolf fans the Three R’s of wolves: The Rise of Wolf 8, The Reign of Wolf 21, and now The Redemption of Wolf 302.

In this third saga, Rick rewards readers with the heartwarming, heartbreaking transi-tion of Wolf 302 from a rambling rake to a responsible adult to a rear guard ready to die to save his pups.

Wolf stories don’t get better than this.

Related Stories

January 7, 2019

Robert T. Fanning, America's Premier Wolf Doomsayer, Passes On

Former Chicago businessman moved to Montana to hunt big game and enjoyed fame as a hater of lobos

August 6, 2018

A Raven's Call Leads To A Hidden Lobo

During a hike in the mountains, what started with a few caws led to the discovery of a stealthily-observant wolf

August 30, 2021

What 'Modern Wolf Management' Looks Like In The Northern Rockies

Cartoonist John Potter says Montana, Idaho and Wyoming have turned one of the greatest wildlife conservation achievements in history into shameful...